The last email I had from Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu, who died early this feast of the first Christian Martyr, Stephen, contained just one word: “Yippee!”

It was sent in response to some news that I’d shared about one of our sons – he called them his “high fivers” since that’s how they’d got to know each other, exchanging high fives – it was utterly typical of the most euphoric Christian I’ve ever known.

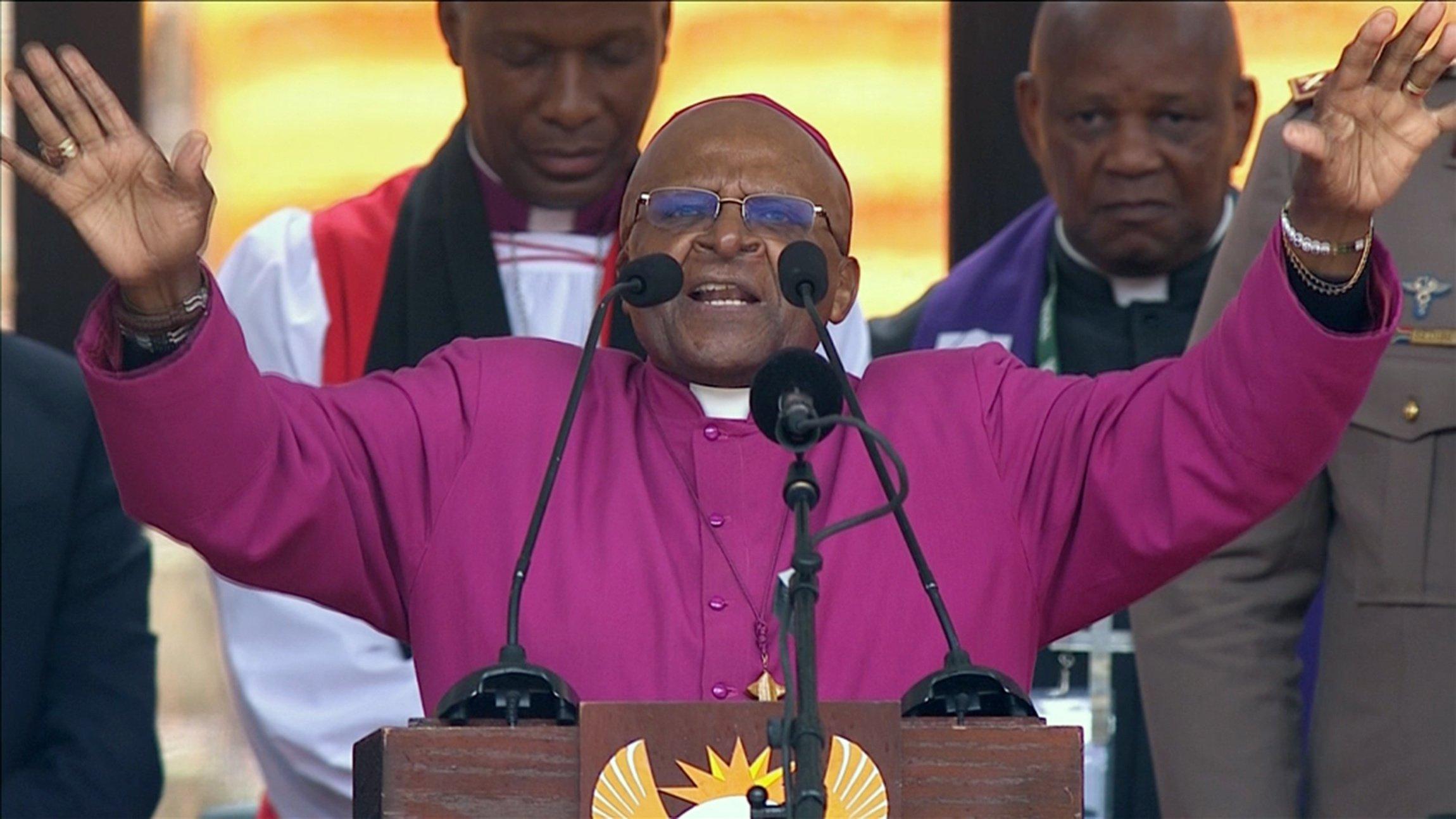

We’d first met in person as South Africa became a democracy and was restored to the Commonwealth at a service in Westminster Abbey in 1994 where the Archbishop had preached at his most irrepressible. I doubt the pulpit there has ever in fact known so much laughter.

For years he used to joke that I had tried to upstage him on this occasion as a photograph of him dancing outside the abbey with the then dean, Michael Mayne, appeared in every South African embassy and High Commission for several years – “With me spotting you,” he’d guffaw, “and you throwing me completely off my step in front of the camera, and ruining my dancing!”

Several years later, when he was again preaching at the abbey for his own hero’s Thanksgiving service – that of Archbishop Trevor Huddleston, who’d been his parish priest in Sophiatown when he was, as he put it, a TB-ridden “urchin” – we again met at the door.

“Have you come to upstage me?” he said, turning from the two distinguished and be-hatted women with whom he was speaking to chat with me for about ten minutes. It was only at this point that he in fact turned back to the two women: “Oh Chris, do meet the Queen of Denmark and the Queen of Spain.”

He was always eminently interruptible – which was doubtless a nightmare for his personal assistants and chaplains – because to him God was always revealed in the minute particulars of human interaction and pastoral encounter. He had seemingly infinite time for people. When he was with you he had that rare gift not simply of making you believe that you were literally the only person he wanted to talk with, but of actually making this a reality. He attended to people with infinite and surely Christlike patience and rapt attention, and was as happy speaking with world leaders as with a street-child on the steps of his beloved St George’s Cathedral in Cape Town. He could never, however, be diverted from his God-given mission to defeat injustice wherever it was encountered.

From the time he came to prominence as dean of Johannesburg in a feisty exchange of letters on the evils of apartheid with then South African Prime Minister John Vorster, through the years he spent heading the South African Council of Churches – hounded by security police at every turn – to his years as bishop of Johannesburg, and archbishop of Cape Town, this voice of the voiceless – since no other opposition leader could speak directly because they were all banned or imprisoned – rallied the world behind the anti-apartheid struggle in a way that made him the stand-out prophet of the age.

No-one who ever heard him speak during the 1980s could doubt his righteous anger, his terse condemnatory tones, his absolute abhorrence of the utterly indefensible racism of which he and his fellow South Africans were all victims. But equally the seeds were already being sown in this recognition that all South Africans were victims – not simply those who shared his ethnicity – of a reconciler who had already been recognised through the award of the Nobel Peace Prize could always transcend anger with its source: that perfect love which casts out fear.

Like Aaron in the book of Numbers and taking his incense burner – Tutu was always by instinct an Anglo-Catholic incarnationalist – he ran into the middle of the plague, the scourge of apartheid that was tearing his people apart, stood between the living and the dead and at length the plague ceased.

No-one, except for Nelson Mandela himself, played as pivotal a role in the birth of the Rainbow nation – a term Tutu coined. And no-one did so with such effervescence and self-giving love.

Weeping with survivors during hearings of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission – for which he was an inspired choice as chair – he revealed a woundedness and humility that was at once painful to see and utterly transforming in its reach. In this way, the Arch, as he was affectionately known, embodied for a generation the very essence of the Gospel – whilst his assertion that God is not Christian maintained his prophetic reach way beyond the limits of denominational Christianity.

In all of this, humour was never far away. He could indeed be extremely naughty. Spotting a tiresome former apartheid cabinet minister when I was chatting with him he remarked somewhat laconically: “Time, I suppose, to smile with old foes.” He simply never gave up on people. He was one of the only Christians I’ve ever met who actually practised the forgiveness he preached – something all too few Christians seem to manage.

One morning, when he was on sabbatical and living at Westminster Abbey where my wife and I did a bit of a meals on wheels service for him and his wife, Ma Leah – which I recall included the delivery of rather a large quantity of rum! – he buttoned-holed me after morning prayer. “My phone has conked out, please could you sort it out?” I walked into their flat to spot the phone off the hook. But to be polite I thought I’d not point this out. So I picked it up and feined some fiddling before assuring him that all seemed to be well. He was half-way up the stairs by then. “I’ve been shown up by the white man again,’ he shouted to Ma Leah, “I always knew these British phones were racist, only responding to white people.”

I’m crying now with laughter as I recall the moment. But who, seriously, after all he’d suffered personally, with and for people, could turn such racism into a joke? Only a person who has made of themselves a lightning conductor for such pain and seen the hints of a rainbow emerge during the storm itself, and dared to chase the end of this rainbow because it heralded the dawn of hope itself. Such is the reality of what we have lost today. May he rest in peace and rise in glory.

Chris Chivers was formerly canon precentor of St George’s Cathedral Cape Town and now teaches at UCL Academy, London

Loading ...

Loading ...

What do you think?

You can post as a subscriber user ...

User comments (0)