It was the mother of Ghislaine Maxwell who first introduced me to the subject of supersessionism. I got to know Betty Maxwell, whose face has become a familiar one on the front pages of this week’s newspapers following the conviction of her daughter in New York for sex offences, when she invited me to help her in organising a conference to analyse the Nazi Holocaust. I visited her at the Maxwell West London home several times, an address since made notorious. I was some sort of press relations adviser, though the proper PR work was subcontracted.

More importantly to her, I was a Catholic who was sympathetic to her cause, but still an outsider to the international community of academics specialising in Holocaust studies and the related more general field of anti-Semitism.

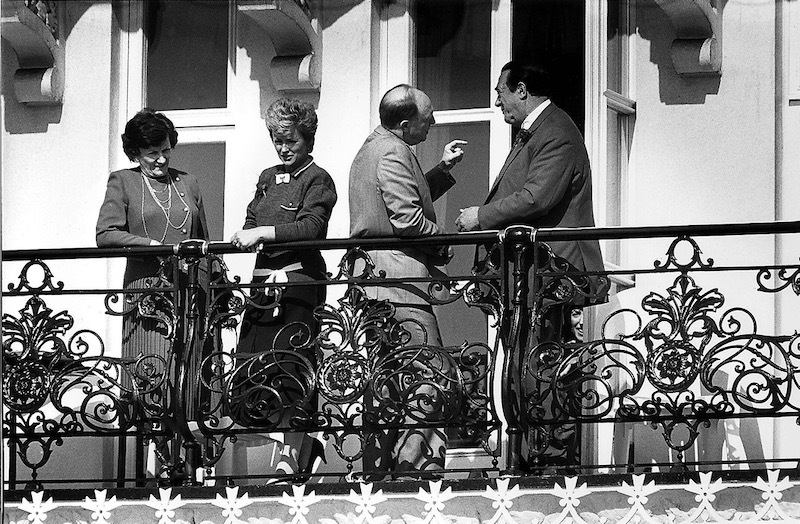

They formed the bulk of the committee she set up to advise her, including top names in the subject such as David Cesarani and Yehuda Bauer. She needed an ally disconnected from these academics, and I fitted the bill. It became a more personal friendship and we remained in touch after her conferencing days were over. (She organised two of them). She was for instance still very interested in the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, the most damaging fraud in history, and the Dreyfus Affair, a scandal still not quite laid to rest. She had a PhD, and was nobody’s fool. Nobody outside her family, at least.

She was from a proud Huguenot background, though her mother was brought up a Catholic. Elisabeth spent time at an English convent school, which explained her perfect grasp of English. From her I learnt that the French Huguenots had a remarkable yet largely unsung record in protecting Jews during the Nazi occupation. Huguenot villages heroically sheltered Jewish families and orphaned Jewish children, at great risk to themselves. There were French Catholic families who did likewise, but the fundamental difference between the two cases was that the French Church at that time was steeped in anti-Semitism, whereas these French Protestants were not.

A French Catholic who defied the Nazis was struggling against their particular religious and cultural tide; a Huguenot was swimming with it. It is worth noting that the French Catholic bishops later recorded their shock and shame at their Church’s failure to stand up against the rounding up and deporting a substantial part of the Jewish population, the great majority of whom were murdered. The major centre for this operation was at Drancy, a name almost an infamous as Auschwitz.

This was only part of Betty’s fascination with the Holocaust. She married a British army officer, Robert, who was himself Jewish and one of very few survivors of a large family network of Jews from Eastern Europe. She researched his family tree and found evidence of at least 300 Holocaust victims to whom he was related.

I have learnt, though not from her, that her relationship with her husband was toxic: he was an autocrat and a bully, perhaps even a psychopath. It seems clear that Elisabeth had no part in or had any knowledge of the crimes that were his later downfall – he siphoned hundreds of millions of pounds out of the Daily Mirror pension fund for his own benefit. But I do suspect that some Maxwell money went into her Holocaust projects, though none in my direction. We carefully avoided all such sensitive subjects. Even though she knew I was a Fleet Street journalist, she trusted me enough.

For me it was an amazing introduction into the field of Holocaust studies, of which up to then I knew no more than the next man. The subject itself was on the edge of a transformation, as official archives across Eastern Europe became accessible to Western scholars following the collapse of the Soviet empire. The search was on for the so-called “smoking gun” – a piece of evidence that tied Adolf Hitler explicitly and in person to the initiation of this fiendish campaign of genocide. But as Betty herself pointed out, all the evidence needed was already there in the pages of Mein Kampf. But the world of Holocaust scholarship was still alert to the need to refute the Holocaust deniers again and again by every scrap of evidence that could be found.

Elisabeth Maxwell’s interest was partly theological. She understood that anti-Semitism was firmly planted in the Christian tradition on the basis of a number of Biblical texts. All Jews living and dead were held to be partly responsible for the death of Jesus, hence the charge of deicide, or god-killing.

But it went deeper than that, touching on Christian self-understanding both of themselves and of the place of the Jews in the divine scheme of things. At first she was drawn to various Protestant theologians and their views on this matter, but she quickly became disillusioned. It seemed to her, she told me, that modern day Protestant scholars were so uncommitted to anything in particular that getting them to repudiate the theological basis of anti-Semitism cost them nothing. Catholic theologians, on the other hand, were subject to a rigorously logical intellectual discipline, and the challenge they faced was a serious one. She respected it.

The watershed in Catholic thinking about the Jews came in 1965, with the promulgation of the decree Nostra Aetate by the Second Vatican Council. It made clear that one of the historical roots of the Holocaust was the tradition of religious anti-Semitism known as supersessionism: that the Jewish Covenant had been cancelled by the appearance of a new one sealed in the blood of Christ. Hence Judaism was nothing but a false religion and the duty of the Catholic Church was to convert them to the real one. Indeed, because of their failure to acknowledge Christ they had been repudiated by God, and deserved nothing but contempt. It is not hard to see how Nazi anti-Jewish ideology found fertile soil in Christian Germany. And if Catholicism was at fault by fostering supersessionism, that is nothing to the vitriolic hatred Martin Luther had for the Jews.

All this was refuted and made anathema by Nostra Aetate, which quoted St Paul’s word in his letter to the Romans to say that God does not withdraw the promises he has made. “What happened in His passion”, said Nostra Aetate, “cannot be charged against all the Jews, without distinction, then alive, nor against the Jews of today. Although the Church is the new people of God, the Jews should not be presented as rejected or accursed by God, as if this followed from the Holy Scriptures…

“Furthermore, in her rejection of every persecution against any one, the Church, mindful of the patrimony she shares with the Jews and moved not by political reasons but by the Gospel's spiritual love, decries hatred, persecutions, displays of anti-Semitism, directed against Jews at any time and by anyone.”

Unfortunately the ghost of pre-Vatican II supersessionism has still not fully been laid, and there are still glimpses of it in the Catholic liturgy. It is present in many prophecies and proverbs relating to the People of God in the cycle of Scriptural readings, especially the first reading from the Hebrew Bible (even the term “Old Testament” has supersessionist resonances). It is taken for granted that the terms “People of God” or “Israel” can be taken as no longer referring to the Jewish religion and people, but exclusively as metaphors for the Catholic Church. They implicitly treat Judaism as superseded. I do not suppose there is one parish priest in a hundred who has ever explained this to his congregation.

But the notion of two “Peoples of God” side by side, both offering salvation but in different ways, is a very hard one for Catholic theology – indeed Catholic identity as a whole – to digest. On the other hand if the idea that the Christian religion has cancelled Judaism is one of the causes of antiSemitism, as Nostra Aetate implies, then this is a serious matter. It could mean the infection of anti-Semitism has not been entirely eliminated from Christian theology, and might still one day burst forth.

That was what worried Elisabeth Maxwell. Her disgraced husband and daughter not withstanding, she deserves to be remembered for it. If there was ever to be another Holocaust conference in the future, I would press for this to be made the central issue – partly in her honour.

Loading ...

Loading ...

What do you think?

You can post as a subscriber user ...

User comments (0)