Tomorrow is Holocaust Memorial Day and as it has drawn closer, I’ve been pondering on pre-war appeasement, and the petition “deliver us from evil”.

Originally, “appeasement” meant simply “the attempt to bring about a state of peace, quiet, ease, or calm”. Only in the context of Britain’s desperate attempts to avoid war in the late 1930s did it gain its pejorative sense of a policy of making political or material concessions to an aggressive power in order to avoid conflict.

The 1930s appeasers were a mixed bag, some of them stubbornly anti-re-armament, seeing it as a provocation, some of them fascist sympathisers, some of them just plain craven.

Churchill said: “An appeaser is one who fed a crocodile – hoping it will eat him last.” But some were honourable men. One of them was Edward Wood, Third Viscount (later Earl) Halifax, who after he became foreign secretary in February 1938 was second only to Chamberlain in his belief that war with Hitler was avoidable.

Churchill nicknamed him “the Holy Fox”. Not only was it a clever play on “Halifax” but also it perfectly captured the combination of political guile and strong religious faith that was the foreign secretary’s hallmark. For Halifax was clever – a Fellow of All Souls – and had known the art of political manoeuvre as Viceroy of India.

As a devout Anglo-Catholic, he made frequent sacramental confession to the Superior of the Community of the Resurrection at Mirfield in West Yorkshire, usually at the end of the week on his way from Westminster to the family seat at Garrowby in the East Riding, where he was Master of the Middleton Hunt.

His was a deep-rooted piety too. His father, the Second Viscount Halifax, had been a close friend of the Rev’d Edward Pusey, and one of the most prominent lay members of the Oxford Movement. Indeed, in 1868 Pusey persuaded him to become chairman of the English Church Union, a society newly formed to promote Catholic teaching and practice in the Church of England.

He went on to play a leading role in the attempts to bring about reconciliation with Rome on the subject of Anglican orders, whose validity had been in question since the Reformation. The attempts proved worse than futile for the cause, however, prompting Pope Leo XIII in the encyclical Apostolicae Curae of 1896 to declare the Anglican orders “absolutely null and utterly void”.

Undeterred, Halifax continued to champion Anglo-Catholicism, not least through his patronage of clerical livings in Yorkshire and encouragement of the county gentry to do likewise. Parts of South and West Yorkshire were long known as “Lord Halifax Country”, or more archly “the biretta belt”.

His son, the Third Viscount, who inherited the title in 1934, had deeply imbibed this Anglo-Catholicism. Exceptionally tall, reserved and patrician, he wasn’t perhaps Churchill’s cup of tea; but Churchill admired his best qualities, if not his judgement on the ultimate threat that Hitler posed.

Curiously, though, unlike Churchill, Halifax had actually met Hitler, and in almost comic circumstances. In November 1937, just before becoming foreign secretary, he’d accepted an invitation to visit one of Goering’s vanity projects – the International Hunting Exhibition in Berlin – which pretext would allow him to meet the Führer’s deputy (Goering) and then the Führer himself.

In his memoirs Halifax relates how on arriving at the Berghof, Hitler’s mountain retreat in Bavaria: “As I looked out of the car window, on eye level, I saw in the middle of this swept path a pair of black trousered legs, finishing up in silk socks and pumps. I assumed this was a footman who had come down to help me out of the car and up the steps and was proceeding in leisurely fashion to get myself out of the car when I heard von Neurath or somebody throwing a hoarse whisper at my ear of Der Führer, der Führer; and it then dawned upon me that the legs were not the legs of a footman, but of Hitler.” The experience did not, however, convince him that Hitler wasn’t a man to do business with.

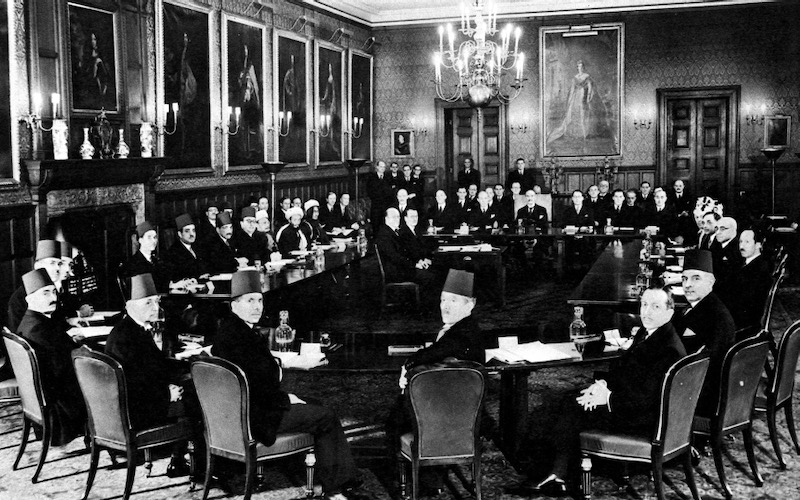

Lord Halifax with Hermann Göring at Schorfheide, Germany, 20 November 1937. By Bundesarchiv, Bild 102-17986 / CC-BY-SA 3.0, CC BY-SA 3.0 de.

Lord Halifax with Hermann Göring at Schorfheide, Germany, 20 November 1937. By Bundesarchiv, Bild 102-17986 / CC-BY-SA 3.0, CC BY-SA 3.0 de.

After the fall of France in June 1940, Churchill told the War Cabinet there would be no negotiated peace. Halifax argued furiously to be allowed to negotiate with Hitler via Mussolini, who wasn’t yet committed to war, but was overruled when Churchill put it to the whole cabinet.

And so in July, as instructed, Halifax reluctantly rejected the German peace offers made through the Papal Nuncio in Berne. He then took a few days’ leave in Yorkshire, recording how he and his wife “spent a lovely summer evening walking over the Wolds, and on our way home sat in the sun for half an hour at a point looking across the plain of York. All the landscape of the nearer foreground was familiar – its sights, its sounds, its smells; hardly a field that did not call up some half-forgotten bit of association; the red-roofed village and nearby hamlets, gathered as it were for company round the old greystone church, where men and women like ourselves, now long dead and gone, had once knelt in worship and prayer. Here in Yorkshire was a true fragment of the undying England, like the White Cliffs of Dover, or any other part of our land that Englishmen have loved.

“Then the question came, is it possible that the Prussian jackboot will force its way into this countryside to tread and trample over it at will? The very thought seemed an insult and an outrage; much as if anyone were to be condemned to watch his mother, wife or daughter being raped.”

This was Halifax’s conception of the German threat. He’d served in the First World War, and the stories of German brutality in Belgium, or “frightfulness” as it was called at the time – the shooting of suspected partisans, including priests, the deliberate burning of the ancient library at Louvain, the swaggering boorishness – would at once have been recalled.

But the threat wasn’t “just” the Prussian jackboot of the 1914 pattern; it was of course far more insidious. At the Wansee Conference in January 1942, when the Nazis decided on die Endlösung der Judenfrage – the “Final Solution to the Jewish question” – Adolf Eichmann of the SS presented the estimate of the number of Jews in Europe, by country, for whom the “solution” would have to be found. On the list was: “England: 330,000.”

How could Halifax have been so wrong? In part as a beneficiary of the churchmanship of the “biretta belt”, as well as being a lover of the sport of foxhunting in God’s Own County, I’d long been interested in the Third Viscount. Ten years ago I discussed him with the journalist and biographer Kenneth Rose, who’d written Halifax’s entry for the Dictionary of National Biography.

Rose, who died in 2014, and whose extensive journals have since been published, was, like me, a Yorkshireman, and had met Halifax on occasions in the 1950s. He’d also been a wartime officer in the Welsh Guards. And he was also Jewish, although non-practising. Indeed, he was a sort of Anglican atheist (or at least agnostic), much attached to the chapels of his old school, Repton, and his alma mater New College, Oxford, and above all the Guards Chapel at Wellington Barracks off St James’s Park.

After we’d talked at length about Halifax’s life and long career of public service, I asked why he thought Halifax had been an appeaser for so long, even once the war had begun. Just how could he have been so wrong? Rose answered very simply that Halifax had no conception that the Nazis – that anyone indeed – could be so thoroughly evil. Only that they were wrong, misguided, errant. And then he added: “I think that it’s the way with many genuinely devout men, that in persisting in looking for good, they fail to recognise – or refuse to recognise – pure evil.”

I’ve reflected long on that conversation. I think that in Halifax’s case it must have been true – until the Holocaust proved the existence of such evil to him beyond doubt. So what? Perhaps this: that when we petition in the Lord’s Prayer to “deliver us from evil”, we understand that first we must recognise evil for what it is. And then to heed the sign that Churchill would have put up: “Do not on any account feed the crocodiles.”

Loading ...

Loading ...

What do you think?

You can post as a subscriber user ...

User comments (0)