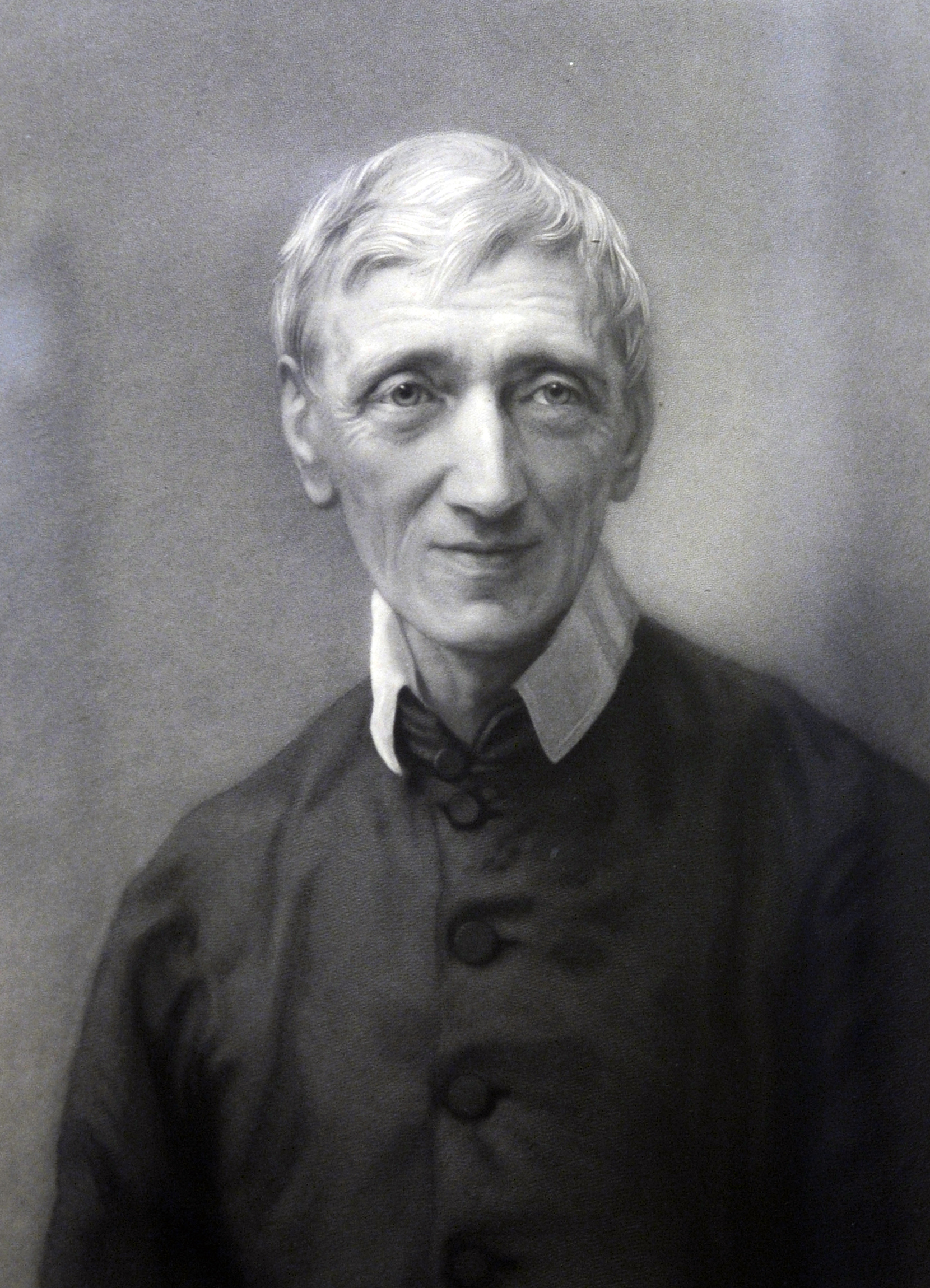

There was a time, not long ago, when librarians locked knowledge away to keep them safe from untrained and malicious eyes. Privileged few walked the stacks, and those who were admitted created yet more tomes for safe keeping. This strategy was not without warrant; after all, how else could they preserve deteriorating archives without walling them off? In the case of the Birmingham Oratory, spatial and financial constraints meant smaller staff with limited public access, so thousands of letters, diaries, photos, and more were packed into boxes and tucked away. Thus, with exception to the published Letters and Diaries (Oxford University Press), which only account for a fraction of the collection, access to Newman’s correspondence remained hidden for over a century. That is, until now.

The National Institute for Newman Studies (NINS), in collaboration with the Birmingham Oratory and the Pittsburgh Oratory, are transforming the way scholars and enthusiasts interact with Newman archives. NINS has scanned nearly 250,000 folios from 165+ boxes, totalling over 40 terabytes (TB) of data. [For comparison: 1 TB = 200,000 5-minute songs on iTunes, or 500 hours of movies]. Even long, multi-page documents, some of which contain 10+ GB of data per document, load on demand. What was once a large and unwieldy collection, locked in a nineteenth century cellar, is now organised and available at the click of a button. (https://digitalcollections.newmanstudies.org).

Research Implications

The archives of the Birmingham Oratory contain the personal papers of Cardinal John Henry Newman and his colleagues who helped establish the English Oratory in the mid nineteenth century. Although most of Newman’s letters have already been transcribed and published in the Oxford University Press, Letters & Diaries, NINS digital collections allow users to view the original manuscripts. And, for the first time ever, users can read thousands of letters written to Cardinal Newman, including letters from ordinary working people to key nineteenth-century religious and political leaders. NINS also has extensive collections from the Catholic aristocracy, and key political figures such as Disraeli and Gladstone, as well most members of the Catholic hierarchy including Cardinals Wiseman and Manning, and Bishops Vaughan and Ullathorne. The letters expose their personal views on topics such as the restoration of the hierarchy and papal infallibility, which opens whole new fields of research on Newman and the Church. Best of all, researchers and enthusiasts no longer need to rely on published transcriptions or travel to Birmingham to view the original documents.

NINS has the largest single collection of published books, articles, and journals on Newman in the world. Within the next year, NINS will publish the majority of these resources online, with full-text search, including options to compare published works with handwritten originals. Furthermore, NINS has a never-seen-before database of Newman’s borrowing records from the Oriel College Library at Oxford. This record makes it possible to compare what Newman was reading concurrent with his writing.

About the Technology

Until recently, image-based resources were locked up in digital silos, with access restricted to bespoke, locally-built applications. Thanks to a growing community of the world’s leading research libraries, NINS can deliver images on a massive scale. Unlike one-off applications of the past—where enormous catch-all software platforms were developed to handle every imaginable task, even at the expense of future change—NINS technology functions more like Legos: different “blocks” of technology are shared across systems and institutions, which gives users a playground to build upon Newman’s legacy. NINS’s new platform rests on three building blocks: 1) the International Image Interoperability Framework (IIIF), 2) a robust and auto-scaling cloud infrastructure on Amazon Web Services, and 3) web applications that tie everything together.

The International Image Interoperability Framework (IIIF) is a set of shared application programming interface specifications (APIs) for interoperable functionality in digital image repositories. An API is a way of standardising code so that data can be shared across applications. Most social media websites, for example, provide an API that allows developers to access user data in order to streamline login for other websites. So instead of building your own login system, you can borrow one from Facebook or Twitter. Similarly, IIIF provides a common language for viewing, zooming, and assembling the best mix of resources and tools to view, compare, manipulate, and work with images on the Web. As long as each library uses the same IIIF API, then image data becomes interoperable and shareable across many systems without the need to develop duplicate software to perform these tasks. Institutions can share common document viewers and other tools designed to talk with the IIIF API. The aim of the framework is to make images portable, shareable, citable, and embeddable, without the need to recreate the wheel for each library.

At its root the IIIF API leverages tiled graphics. That is, images are encoded using an algorithm that divides the images into tiles—much like cutting a cake into slices for consumption piece by piece. The algorithm also saves different resolutions of the same image into a pyramid of layers, sort of like a multi-tiered wedding cake, with smaller versions of the same cake stacked progressively higher (see Figure 3). A single high-resolution image might contain thousands of separate slices and dozens of layers, which allows applications to use the IIIF API to grab individual slices without downloading the entire file. One person can’t eat a wedding cake all at once (well, we shouldn’t, anyway); so, too, Internet browsers can’t render every pixel simultaneously. Thus, high resolution images when zoomed in on a IIIF document viewer are rendered from slices at the highest resolution layer of the stack, while low resolution images, such as thumbnails, are taken from the smallest resolution layer of the pyramid. In either case, the process requires bytes instead of megabytes. And using the common language of the IIIF API, images can be embedded on other websites, too, all without changing the original file or replicating data on remote servers. IIIF image servers can also flip, rotate, skew, crop, colorize, and much more, all on the fly. And since the heavy lifting is done in advance by the image servers, the user experience is very fast.

The high-speed computation behind IIIF and NINS data is powered by a custom designed network of Amazon Web Services (AWS). Original high-resolution TIFF images are backed up on local drives and uploaded to AWS Glacier, which is a low-cost, scalable image bucket for emergencies only. The images are then converted to pyramidal JPEG-2000s (JP2s), including slices and layers necessary for IIIF image servers, and uploaded to AWS Simple Storage Service (S3). Behind the scenes the images in S3 are automatically synced with AWS Elastic File System (EFS), which are servers that sit closer to NINS IIIF image servers for increased speed. The image servers render images from EFS in an auto-scaling cluster of Amazon Elastic Compute Cloud servers (EC2), which expand or shrink based on processor and memory loads. An important part of NINS’s secret recipe is the Kakadu image processor that compresses and decompresses JP2 images and the IIIF-compliant Cantaloupe image server where it resides, both of which run on EC2. This digital progression of acronyms (yes, its difficult for us, too) from Glacier to S3 to EFS to EC2--that is, from raw images to image servers/processors--happens before documents are ever added to the website, which is part of the reason that documents load so quickly.

The server-side technology comes to life on NINS’s sleek and mobile-ready web applications, one for curators, and another for end users. They are built using MongoDB, Angular, and Node, and they include IIIF resources from other institutions such as Mirador (document viewer), Leaflet (image viewer), the Bodleian Library Manifest Editor (IIIF JSON editor), and more. The initial launch of the software includes search functionality with detailed filters, deep-zoom, multi-document comparison, full-screen mode with draggable document panes, full document metadata, and related documents. NINS’s immediate roadmap (available by October 2019) includes optical character recognition, full-text search on published documents, transcription panes for handwritten documents, advanced search options, and data visualization. NINS curators have carefully analyzed bibliographic data for the first 60 boxes (over 30,000 pages), and the first batch of folios is available online with several hundred new documents added per day.

Implications for Digital Humanities

NINS is on the cutting-edge of library science. Dizzying amounts of data can be streamed simultaneously to end users and other institutions. Image-based resources remain in their original, high-resolution format while image servers and image processors apply algorithms that render them in endless configurations; cropped, flipped, sliced, colorized, resized, etc. It’s a curator’s dream! Precious resources are preserved while granting unfettered access to the world.

NINS digital technology makes possible things that are simply not possible in a physical library. For example, IIIF-rendered pages of documents from multiple locations can be stacked on top of one another in a single digital canvas. This means that manuscripts separated at birth--e.g., a torn letter with fragments from different archives--can be re-stitched together for a seamless viewing experience. Users can manipulate images (without harming originals) by applying deep zoom and image editing tools beyond anything possible to the naked human eye. Furthermore, annotations such as metadata, transcriptions, notes, links, videos, supporting documents, can be stacked onto the same canvas, and in the same document, and stored in non-relational, high-memory databases and search engines. And, since the data conforms to W3C web annotation standards, or “linked data,” the world can comment on, describe, tag, share, and link to NINS resources with ease. This data structure opens the door to advanced data visualisation and interoperability with other technologies, institutions, and academic fields. NINS has unlocked their cellar doors, and they can’t wait to see what scholars will do in their new digital playground.

Daniel T. Michaels is Chief Technology Officer for the National Institute for Newman Studies

Loading ...

Loading ...

What do you think?

You can post as a subscriber user ...

User comments (0)