Jesus is driven out into the wilderness. That would have evoked powerful if contradictory associations for any first century Palestinian Jew. For one thing, much of Palestine is wilderness, uninhabitable and largely barren land to both east and south, suitable only for meagre pasturing. The book of Deuteronomy describes the southern desert, for instance, as “great and terrible, with venomous serpents and scorpions and thirsty arid ground”. 1 It was popularly believed that demons dwelt there.

For first-century Palestinians, then, the wilderness was a place where you were at the mercy of life’s extremes. It was also associated with sin and failure: in the wilderness Israel had been tested and found wanting, when the people substituted a craven idol for the living God who had brought them out of Egypt. And yet, the wilderness was also where Israel first encountered God. So the prophet Hosea can speak of God leading Israel back into the wilderness, in order to speak directly to her heart once more and reclaim her love.

The wilderness, in other words, was as much a place of trysting as testing; a place of terror, to be sure, but also a place of tenderness. All these allusions are present throughout the gospels. So, for instance, when Jesus is tested (rather than tempted) in the wilderness, it is an immediately recognisable echo of Israel’s testing, though this time without sin and failure in its wake. The testing of Jesus in the wilderness is graphically depicted as a struggle with Satan, a conflict concerned as much with motive as act, the head and the heart, as much as the hand.

These allusions are helpful as we embark on our own forty days in the Lenten wilderness. The early desert Fathers called the wilderness “a place for the weighing of the human heart”. We, of course, don’t go out to the wilderness: rather, we withdraw into the wilderness, the wilderness created within by whatever penance we’ve adopted. The purpose of that penance is to create a space within in which to encounter God by confronting our real needs and acknowledging our deepest desires: a space and stillness within, in which to come face to face with the me I’ve created through my free choices, in order to become more fully the self created by God’s free choice. Lent is a time for undistracted honesty, a time for refreshing not both our perceptions and our motivations, so easily muddied and muddled, by prejudice and self-regard, on the one hand, or fear and faintheartedness, on the other.

It was Jesus’ humanity that was tested, the humanity he shares with us. His testing is a reminder that there is in every human being a continuous struggle, a ‘warfare in our limbs’, a fight for integrity, for harmony between head, heart and hand. But Lent has nothing whatever to do with obsessive introspection. The ascetical practices of Lent are not about self-improvement and human perfectibility.

We shouldn’t be even trying to make ourselves presentable to God: it can’t be done. We can’t earn God’s love; and we don’t need to. He knows us infinitely better than we will or can ever know ourselves, and still loves us. God sees our sins more clearly than we do: he knows our disordered cravings and failings and in Lent we entrust everything to his healing power and ask for the grace to know our need of God. This is, of course, easier said than done.

There’s a moment in Graham Greene’s The Power and the Glory when the failed and forlorn “whisky priest”, at risk to his own life, is hurriedly hearing whispered confessions. He says, by way of encouragement to an elderly woman penitent: “Remember your real sins.” To which she replies indignantly: “But I’m a good woman, Father.” “Then what are you doing here,” he says to her, “keeping away the bad people?”

But owning our sinfulness is the absolute precondition of acknowledging the sheer gratuitousness of God’ love for us, because he meets us precisely where we most need him, in the confusion and chaos of our real lives. And our fasting (or whatever we choose to do or not to do) during Lent is a token, an expression, of our desire for God. But outer fasting will contribute nothing, except corrupting self-satisfaction, unless it’s an expression of inner fasting that concerns the heart. We’re to fast, first and foremost, from all that doesn’t have love and compassion as its motive and goal.

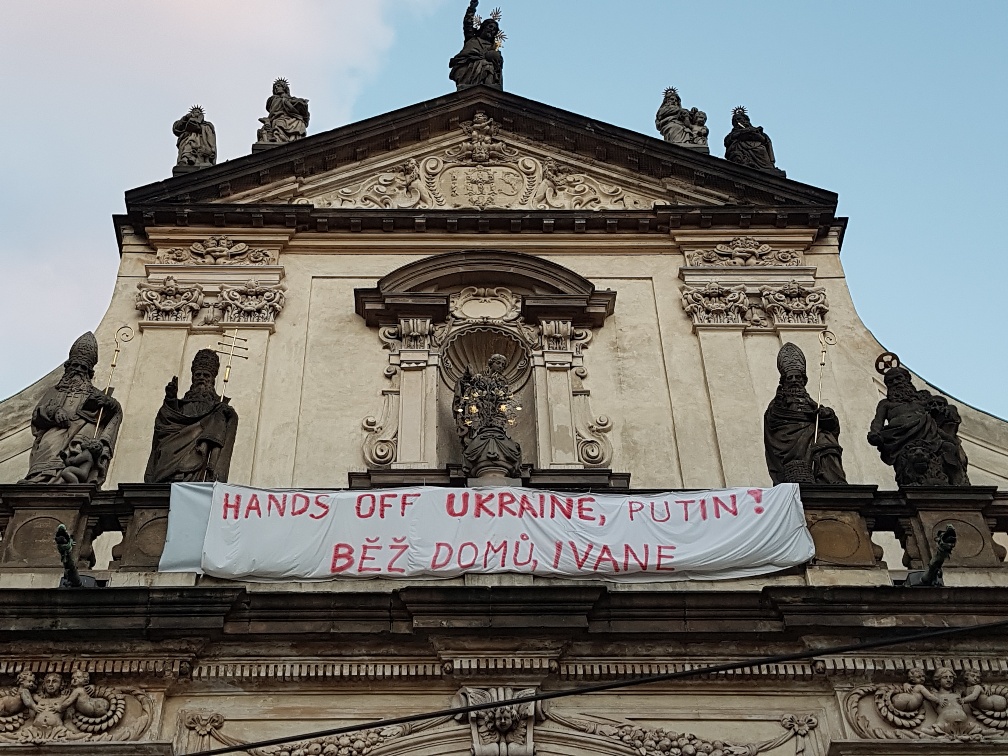

Where love and compassion are absent, what the Germanborn American political philosopher, Hannah Arendt (1906- 75), called radical evil all the more easily fills the vacuum. She was commenting in the aftermath of the Second World War on the totalitarianism that dragged the world into violent conflict, pointing to the calamitous consequences of power that is prepared to do anything to prove that anything is possible to the person preserving himself in power. The radical evil that sucked the whole world into war is once again in view.

The other casualty of totalitarianism, of course, is always truth. To twist truth to serve the murderous pursuit of power wreaks havoc not only on the lives and relationships of countless others but also on the inner life of the perpetrator. No one is left unharmed. When St Antony, the first of the desert fathers, went out into the wilderness, he was immediately beset by all the demons he carried within himself: lust, avarice, anger, vanity, pride, despair. If in our wilderness, we uncover similar things in ourselves and are able freely to acknowledge them, we are blessed; because it’s only by owning the truth about ourselves that we become receptive to God, the Truth Itself, who reaches out to us.

Loading ...

Loading ...

What do you think?

You can post as a subscriber user ...

User comments (0)