A sermon should provide a bridge between the world of the biblical text and the world of the listeners. This is no easy task in a world that in these dramatic times changes literally every day. I do not dare predict what is going to happen in the days between my composing this sermon and the Sunday when I am going to preach it.

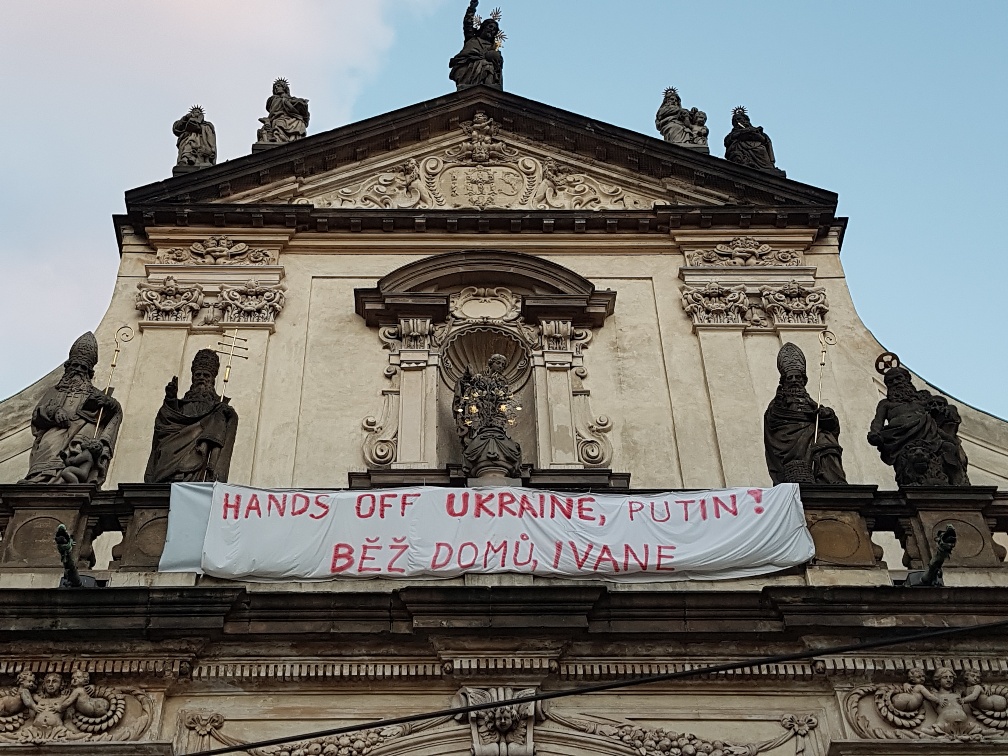

Just a short time ago, very few could imagine that Europe would be at war again; that Vladimir Putin’s Russia would exclude itself from the family of civilized countries: committing war crimes; violating international law; perfidiously and despicably attacking its weaker neighbour; and seeking to erase a democratic country from the map of the world by brutally killing its citizens, including women and children. The blood of Ukraine cries out to the Lord of hosts.

We began Lent with the rite of the cross of ashes, accompanied by the words: “Remember that you are dust and to dust you shall return.” This rite and these words confront us with our mortality, our death. They lead us to adulthood, maturity, and responsibility. After Lent is over, we celebrate Easter, the holiday of the glorious victory over death and the fear of death. Then we can ask: “Where, O Death, is your victory?” Scripture tells us that we were held in bondage through the fear of death. However, we are called to freedom, to freedom from fear. The purpose of Lent is internal transformation. It represents an opportunity for liberation and re-creation.

The imaginative account of the creation we read in the Bible tells us that the human being is a great paradox: taken from nothingness, from the dust of the earth, we are brought to life through God’s spirit. Dust and ashes symbolise nothingness; something that can be swept away in the blink of an eye. God alone can create things out of nothingness. God alone can endow nothingness with a form, a shape, a face, and a meaning; in short, God alone can endow it with God’s spirit. And so, a human being, vulnerable and finite, becomes – through the power of God’s spirit – an image and expression of God’s freedom and creativity.

When we abuse the gift of freedom, when we encapsulate ourselves in the shell of our selfishness to stay away from the blowing of God’s spirit – in theological language, this self-enclosure is referred to as sin – we fall back into nothingness. In Psalm 104 we read: “When you take away their breath, they die and return to their dust.” But the psalm immediately speaks of repentance, a transformative change of heart, as re-creation: “When you send forth your spirit, they are created.”

This shift from nothingness, sin, and self-closure as spiritual death and, especially, this transformation of heart and forgiveness as the resurrection and awakening to full and liberated life that our Lenten preparation for entering into the Easter drama of the victory of life over death guilt, and fear is all about.

We need to have our faith, our love and our hope resurrected. Let us not mock God’s call by turning Lent into a time when we give up eating chocolate. The years to come will bring more than enough asceticism. In the time of the coronavirus, God closed our churches to tell us: If you have thought that your Christian faith lies in leading a decent life and attending church on Sunday, then beware: that is not enough. The motto of Lent is, seek the Lord while he may be found.

God wants us to courageously, creatively and generously seek new, more profound, and more challenging ways to think about and live our faith. Pope Francis’ call to a synodal reform goes in the same direction: to transform the Church from an institution where we all march in lockstep into a network of mutual communication, a path of searching together for responses to the signs of our epochal times. Neither escapism into the past, nor cheap modernisation – but a demanding journey from superficiality to profundity.

The gospel reading for the first Sunday of the Lent season reminds us that Jesus went through 40 days of fasting in the desert. When he stepped out of the shadows of anonymity and was baptised in the Jordan, Jesus was recognised by both John and the divine voice as the long-awaited Messiah and the beloved Son of God. And yet, rushing from his baptism straight into the streets of the world is not what he does. Instead, he goes alone into the desert. For the next forty days he will be tested, as the people of God were tested during their forty-year journey through the desert from slavery to freedom.

The desert was not considered a place of peaceful contemplation, but a place where demons dwelled. Hermits would not go to the desert to enjoy solitude but to grapple with the spirit of evil on his home turf. Those who retreat into solitude, silence and fasting should expect nothing pleasant. Silence and solitude can expose our shadow, the side of our personality we have suppressed or drowned out with leisure and noise. When we feel down or abandoned, we often look for a way out in eating and drinking; when we experience hunger, we can be mean and hostile. Manifold temptations arise in the soul of one who is frustrated. Similarly, Jesus, too, was tempted when he was hungry. All three of the temptations he faced in the desert strove to counter the role of messiah that he had accepted at his baptism and had refined in the solitude of the desert.

Of all the messianic images familiar at that time – often featuring victory over the Roman occupiers and restoration of the might and glory of David’s kingdom – Jesus identifies himself with the one described by the prophet Isaiah: the Messiah will be a man of suffering who bears the transgressions of all people and is killed like an Easter lamb: yet it is through his wounds and scars that many will be healed.

Craftily using scriptural passages out of context, the devil offers Jesus a completely different image of the Messiah: a messiah without a Cross, a messiah of success and impressive miracles, a messiah of might and glory who is revered and enjoys popularity. Turn these stones into bread and feed yourself and all those who are starving! Find solutions to social problems! Establish a reign of affluence! Throw yourself headlong off the roof of the temple – and you will be fine. Quite the contrary, all will applaud you! Indulge yourself in royal authority over the whole world. It is a real bargain – it will only cost you a single bow before the Lord of Darkness. No Cross but a golden throne instead!

But Jesus knows that a Christ without the Cross would be an Antichrist. The Church without the Cross would be merely another of the powerful institutions of this world; the priest without the Cross would be a mere office-bearer, agitator, and ideologue. A Christian without the Cross would be merely a member of an institution, simply the proponent of an ideology or worldview.

When Christ started saying that he is about to go on the path of the Cross, Peter – whom Jesus had commended a short time earlier for his messianic confession and had referred to as the rock on which he would build his church – tries to talk him out of it. Everything is fine; you can avoid all this suffering, he assures him. This is when Peter hears the harshest words that ever came out of Jesus’s mouth: “Get behind me, Satan!” In Peter’s soothing words, Jesus discerns an echo of Satan’s temptation in the desert.

And the same temptation comes for the third time in the hour of his death: Come down from the cross and we will all believe in you! Martin Scorsese’s film The Last Temptation of Christ, adapted from Nikos Kazantzakis’ novel, portrays the greatest temptation on the Cross: Renounce your way of the Cross! Live a “normal life” like anyone else! Though many Christians were offended by the book and by the film, both end on a very orthodox note – Jesus resists the temptation, returning to the Cross.

Jesus does not use magic to turn stones into bread. Instead, he gives his flesh and blood, his whole being, thus becoming the bread of life. Jesus smashes himself on the pavement of this world, rejecting the safety net provided by the angels. Instead, he drinks the whole cup of suffering without running away from the burden of human destiny. Jesus has been given all authority on earth and in heaven. However, it is not a reward for devil worship. Instead, it is a fruit of faithfulness to the will of the heavenly Father.

“Say No to the Devil.” This is a song that the Czech Protestant minister and dissident Sváta Karásek sang following the Soviet occupation of Czechoslovakia. He confronted the police regime, its intimidation and its temptations and promises. Our world is once again threatened by the powers of darkness. From the same place that sent us a great frost in 1968 – a frost that burned the yearning for freedom in our country for the next twenty years – are again coming lies, blood and the fire of destruction, tempting the world to give way to selfishness, aloofness, and the foolish belief that everything is fine, that we can avoid suffering. It is not true. Let us not lull ourselves into a false tranquillity. Let us be defiant: Say No to the Devil.

Tomáš Halík is professor of sociology of religion at Charles University, Prague, where he was born in 1948. Under the communist regime, he was secretly ordained as a priest in Erfurt and was active in in the underground Church while working as a psychotherapist. He has received numerous international awards and prizes for his contribution to the Church in times of persecution, and for dialogue between religions and cultures. He was awarded the Templeton Prize in 2014.

Loading ...

Loading ...

What do you think?

You can post as a subscriber user ...

User comments (0)