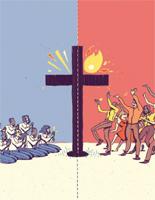

Their churches are increasing in number and popularity in Britain, particularly among African migrants living in urban areas. If Catholic parishioners leave the pews to join Pentecostal services, should their priest regret it? Or adapt to be more like them?

Recently, an Afro-Caribbean man came into the parish office to express concern that his youngest child was ready to start at our parish primary school but was not yet baptised. I told him that I had reminded his Congolese partner several times about the baptism. I also mentioned that I had not seen her and their other children, all baptised, at church over Christmas, indeed, for some time. “She now goes to a Pentecostal church,” he replied.

This is happening time and again: the drift of active parishioners, mainly African, but not exclusively, to Pentecostal churches. Over a year ago, we lost our youth group leader to one.

There are probably more families with children at our primary school, all baptised Catholics, who go to Pentecostal churches than their local Catholic parish church. Sometimes a parent will call me “Pastor” instead of “Father”.

On one level, what is happening is very dispiriting. As a result, we have encouraged our main Sunday morning Mass, which has a large number of families at it, to have a more vibrant feel. The choir is made up mainly of African mums and their children, who sing with great gusto. Frequently – not every Sunday – we have an offertory procession with swaying and singing women bringing up gifts of toilet rolls, washing powder and other sensible things for parish use.

On New Year’s Eve we have a bigger Midnight Mass than at Christmas, as Africans love to see in the new year in church. We have set up a Nigerian Association in the parish and established the Knights of St Columba (to be a “knight” is important for African men).

Still the drift continues. I know in my bones that we would have a bigger and more vibrant congregation but for this “Pentecostal drift”, as I call it. On the other hand, I sympathise with those who find Pentecostal worship livelier and more fulfilling spiritually. There is probably also a greater sense of community, and of collective and open faith-sharing in those churches, which the British/Irish are not good at.

Africans want to give thanks vocally to God and express their joy at his goodness to them. Catholic worship is too formal and constraining to allow this to happen, except in a completely African context in Britain. We have to make allowance for other ethnic groups in the congregation. Also, the preaching is more biblical, and Bible reading is encouraged more than in the average Catholic parish. In Pope Francis’ terms, they are probably experiencing more evangelii gaudium, sheer joy at listening to the Good News. So part of me is happy for them.

Then I find myself arguing that the Catholic Church is more doctrinally serious, that it has religious gravitas. After all, the Pentecostals are subject to the whim of their pastors, who have no one to police their preaching and challenge their often outrageously fundamentalist reading of the Scriptures. And then there is all that “health and wealth” stuff: follow the Bible and you will be successful, have a good job, bigger house and enjoy better health.

But another part of me feels uneasy with that assessment. The sheer exuberance of Pentecostal worship is surely telling its own story. “By their fruits ye shall know them” – and the fruits are joy and sheer delight at God’s munificence, even in adversity. Why can’t we communicate that same joy in most of our Catholic churches in Britain?

Often, when I look at the congregation at Mass from my vantage point behind the altar, I ask myself the question, “What brings them here week after week?” There is often little joy on their faces or in their body language. One reason I went in for the priesthood was because it had become too painful for me to stay in the pews. Had I not become a priest, I am convinced I would have lapsed.

Pope Francis hit the nail on the head in his recent apostolic exhortation when he said that we should not look like people who have just returned from a funeral. Is it any wonder, then, that our congregations are shrinking, except in London and other urban areas, where immigrants, often African, are rejuvenating our parishes with their unselfconscious faith in God’s presence in their lives (unless, of course, they have moved to the Pentecostal church).

On the day some years ago when London shut down because of heavy snow and not a single bus ran, two African parishioners told me they got to work that day by bus. I said that was impossible. They looked at me with some astonishment at my lack of faith and said, “We prayed to God and a bus came.”

The other day a Nigerian woman, who lives in a council flat with two unemployed sons, thrust a very substantial cheque into my hands for our church restoration fund. “But how can you afford it?” I said. “God has been so good to me, Father, this is the least I can do to pay him back and show my gratitude,” was her sincere reply.

After eight years in London’s multicultural East End, I am convinced more than ever that a fundamental part of my job as a parish priest is to provide the conditions for my parishioners, wherever they are from, to worship, thank and praise God. And if a worryingly high number of those parishioners are going elsewhere to do just that, then I have to ask myself, and the Church, the question, “Why?”

I suspect the answer may be quite a complex one. After all, in the 1970s and 1980s the charismatic renewal movement had an opportunity to rejuvenate our parishes and bring joy back into worship. Such a renewal met with some success but never became widespread, and is now on the wane.

Neither do I see a return to more formal and ritualised worship as the answer, and I am not against either formality or ritual in the liturgy. Putting six large candlesticks and a crucifix on an already overcrowded altar to try to shoehorn the Missa Normativa into a pre-Second Vatican Council style of worship may work for some, but is not in my view the vehicle for those who want to express their joy and delight at God’s presence in their lives.

Pope Francis has courageously named an “ostentatious preoccupation for the liturgy” (Evangelii Gaudium, 95) as one of the problems in the contemporary Church. Apparently, he incurred the wrath of some of his former flock in Buenos Aires by going to a Pentecostal service and being prayed over. With that simple gesture, he made it clear that he respected them and acknowledged the healing presence of the Lord in their worship.

So maybe we need to reassess our attitude to Pentecostalism and look on it in a more positive light, while acknowledging the many problems, not least the “prosperity gospel” and the showy wealth of some pastors. The Canadian theologian James K.A. Smith is helpful here. He, too, sees the drawbacks of the prosperity gospel, but he also sees in it a profoundly incarnational theology.

As Smith puts it in his study, Discipleship in the Present Tense: reflections on faith and culture: “It is evidence of a core affirmation that God cares about our bellies and bodies.” Implicit in it is a belief that God is concerned not just for our souls but also for our material well-being, which is not too different from the theological impulse behind work for justice and peace.

Both the prosperity gospel and Catholic Social Teaching arguably belong to the same stable, with the same potential for each to become distorted in its own particular manner: the prosperity gospel distorted by the pursuit of ostentatious wealth, and a misunderstanding of social teaching leading to concern for social issues that becomes merely political. Both need to be tempered by an awareness of the provisional nature of all earthly endeavour in the light of God’s Kingdom.

But that Kingdom is in the here and now as well as not yet.

So instead of bemoaning the drift of some of our parishioners to the Pentecostal churches, perhaps I should rejoice in the diversity of God’s gifts and expressions of Christian faith. And if there are any lessons to be learnt, I should be humble enough to admit that perhaps I am not meeting the spiritual needs of my flock in the way that I should be. In fact, I might follow Pope Francis’ example when he was an archbishop and go along to a Pentecostal service to be prayed over!

* Paul Graham OSA is parish priest of St Monica’s, Hoxton, London, and provincial of the Augustinians in England and Scotland.

Loading ...

Loading ...

What do you think?

You can post as a subscriber user...

User Comments (1)

Sometimes the word spreads slowly as it spreads widely. I am at least the third reader of this issue, and it is a topic that interests me. I would be interested in knowing what the response has been and what conclusions or recommendations have emerged.