The more I work in the field of human rights advocacy, the more convinced I am of three essential principles: the importance of regular rest, retreat, renewal; the need for unity among those who share a common cause; and determination, whatever the weather.

On a recent long weekend break in Norfolk, I received reminders of all three.

I had not been to Norfolk since a childhood holiday on the coast in Blakeney as a toddler. Since becoming a Catholic almost 11 years ago – in Myanmar (Burma) – I had always had a desire to go to Walsingham, and also to Norwich.

So last weekend I fulfilled both wishes. Packing a small suitcase ridiculously crammed with books – far more than I could get through – I jumped on a train from Liverpool Street to Norwich and began a new adventure.

Soon after arriving on Friday, and after checking into the Maid’s Head Hotel – the oldest hotel in the country – I went to evensong in the Anglican cathedral next door. I have no regrets whatsoever about becoming a Catholic a decade ago, but as a former Anglican, if there is one aspect of my old tradition that I still cherish it is choral evensong in our great cathedrals.

As I walked around the close and cloisters in Norwich Cathedral, I sensed the history and spirituality of a place where prayers have been said for over 900 years in this one-time Benedictine monastery.

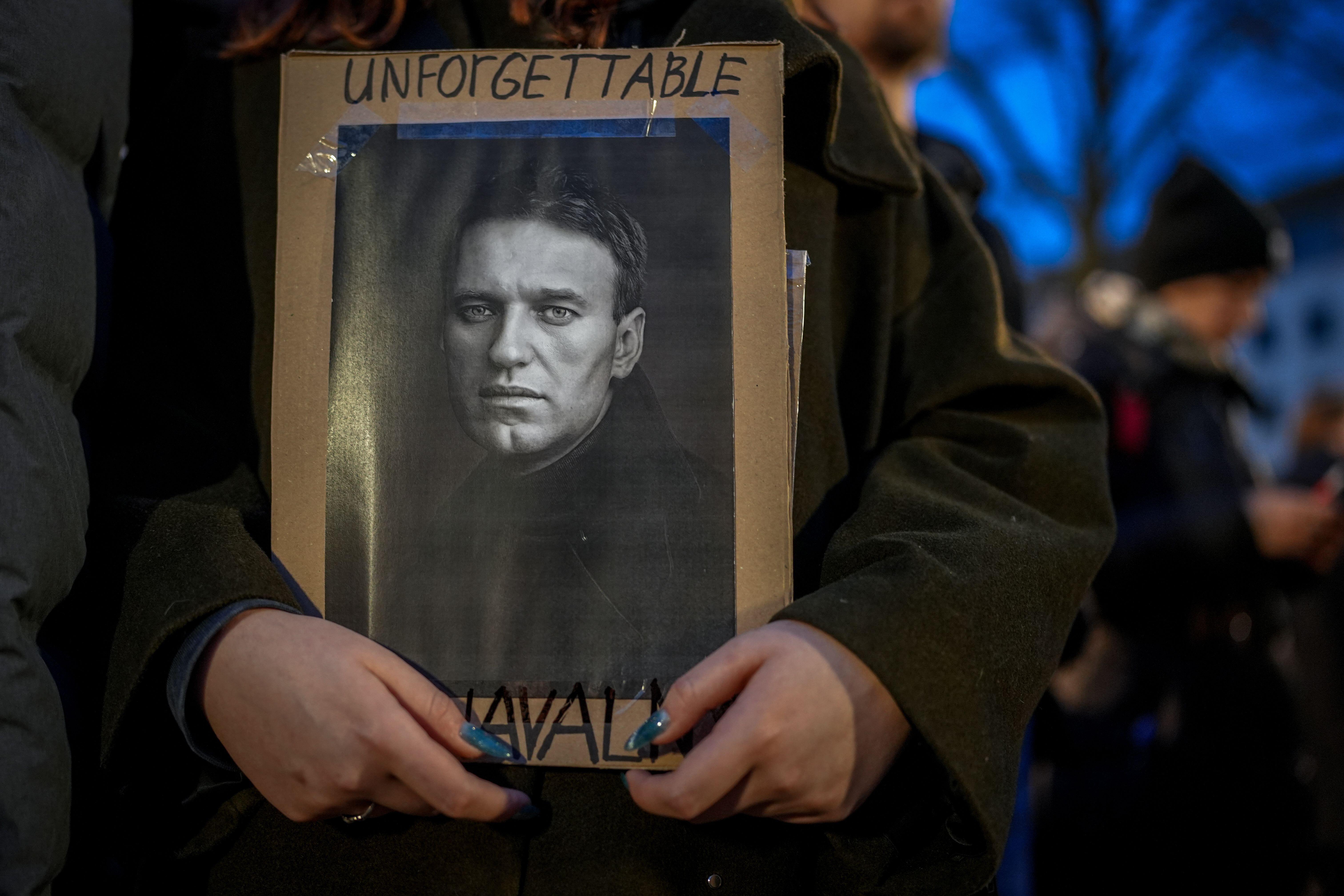

The next day, I made another visit to the cathedral and its cloisters and grounds. There I lit candles and said prayers for the causes that are most on my heart. I littered both the Peace Globe and the Prayer Board with requests and multiple candles: for my friend Jimmy Lai, a 76 year-old entrepreneur, devout Catholic, pro-democracy campaigner and British citizen in Hong Kong who has been in jail for over three years and faces the prospect of the rest of his life in prison; for all other political prisoners in Hong Kong, many of whom are my friends; for the Uyghurs and Tibetans, for persecuted Christians and Falun Gong practitioners across China; for the people of Myanmar, especially Aung San Suu Kyi, my friend Dr Sasa, a key spokesperson for the government-in-exile, and for Myanmar’s Cardinal Charles Bo; for North Korea; Ukraine; Israel and Gaza; and of course for the family and friends of Vladimir Putin’s murdered opponent Alexei Navalny, and all Russians who desire freedom and peace.

I repeated those prayers and lit those candles again and again, in every place of worship I visited, across Norwich and Walsingham. In Walsingham I implored Our Lady repeatedly to intercede for these causes. Like the persistent widow in St Luke’s gospel, I was going to hammer on their doors until Heaven and Our Lady got the message.

After a walk along the river, I visited St Julian’s Church, on the site where the fourteenth-century anchoress Julian of Norwich once lived. I had already brought her Revelations of Divine Love among the many books in my creaking suitcase, and so it was beautiful to sit for a few moments in Mother Julian’s cell and ponder her words: “God is everything that is good and the goodness that is in everything is God.” I also reflected on her reminder that “God wishes to be known, and is pleased that we should rest in him.”

I then went around the corner to the simple Visitors’ Centre, where I received a wonderfully generous welcome. Offered coffee, I sat with a retired vicar who used to preach in St Julian’s Church, whose wife was having a cataract operation. He, on the other hand, was off to watch Norwich play Cardiff in the nearby football ground with his friend. We were joined by a former London policeman who had decided, while his wife went shopping, to come and pray in the Shrine of Julian of Norwich. We shared stories and experiences, discovered multiple common threads, and I marvelled at the blending of the sacred and the secular, the spiritual and the worldly, the sublime and the day-to-day.

On Sunday, I went to Mass at Norwich’s other cathedral, the Catholic Cathedral of St John the Baptist, where we heard a truly inspiring homily for the first Sunday of Lent from a visiting Indian-born Augustinian priest, Fr Gladston Dabre.

I loved the fact that in Norwich my Anglican roots and my Catholic faith were reunited in a particular way, intertwining evensong in the Anglican cathedral and Mass in the Catholic cathedral, together with an ecumenical devotion to Julian of Norwich.

After Mass on Sunday, I faced a choice. I had seen much of what I wished to in Norwich: the cathedral, the castle, St Julian’s Church, the river. I had a heavy cold coming on and the weather was not enticing. Sunday began with a downpour and threatened further showers. It would have been easy simply to spend the rest of the day in my hotel room with my suitcase of books.

But an inner voice told me that I could do that at home. I should get out and explore. And so I hopped on a train to Hoveton and Wroxham, to explore the entry to the Norfolk Broads. With my umbrella up, I walked through pouring rain alongside the River Bure for a little while, and then jumped on a train to Cromer to see the coast. By the time I got to Cromer, the skies had cleared and a little sunshine had appeared, and I spent the rest of Sunday afternoon strolling along the sandy and pebbly beach and along the clifftop.

And then from Norwich, it was on to the real heart of my journey: my first ever pilgrimage to and retreat in Walsingham.

Ever since becoming a Catholic over a decade ago, I had heard about Our Lady of Walsingham. To be honest, when I was first exploring Catholicism, while I had no doubt about the value of honouring Our Lady, I became slightly confused about the different places and names: Fatima, Lourdes, Knock, Mount Carmel, Guadalupe and Walsingham. I was always curious as to why a tiny Norfolk village merited an “Our Lady” title.

Over the years, I made several attempts to visit Walsingham to learn more, but each time was thwarted: either the pilgrim houses were booked up or they were closed at that time of year. This time I had a few days in my schedule when I thought I could go. I tried to book at the Catholic pilgrimage accommodation, but – to coin a phrase – there was no room at the inn. “Try the Anglicans,” I was told. I did, and they gave me a room.

I spent a blissful 24 hours in Walsingham. I prayed at the Anglican shrine, in the Holy House, and ate with fellow pilgrims in the refectory. I walked beside the snowdrops in Walsingham Abbey gardens.

Twice I walked the Pilgrim Way to the Catholic National Shrine and Basilica of Our Lady of Walsingham, one day in beautiful gentle sunshine with birdsong in the bushes and the next day with howling, bracing winds biting at my cheeks.

On the second day, on the way to Mass at the Catholic shrine, I contemplated turning back several times, as the weather was so unpleasant. But a voice within told me: “This is the whole point. It’s one thing to stroll along to Mass with the sun in the sky and the birds singing and a song in your heart. It’s quite another to push through the wind and the chill.” I understood the message and kept going: and I was glad I did. Ours is not simply a fair-weather faith: it’s a faith for all times, good and bad, joyful and tough, otherwise it ain’t a faith worth following.

What I loved about Walsingham was that the labels “Anglican” and “Catholic”, while there in writing, were almost completely dissolved in spirit. I saw little difference.

The only thing that surprised me was just how Catholic the Anglican shrine and pilgrims were. I came into the Catholic Church from the evangelical, moderately charismatic, low-church end of Anglicanism. Although I was aware of it, I had little prior encounter with Anglo-Catholicism. But meeting pilgrims at the Anglican shrine and joining evening prayer and shrine prayers, I would be hard pushed to see the difference between their Catholicism and mine. We prayed the Rosary; we genuflected to the Blessed Sacrament, we venerated Our Lady; the clergy were referred to as “Father” and they celebrated “Mass”; confession was offered. I found myself thinking: why don’t they make the whole journey, as I did, and swim the Tiber?

But whether they do or not, the intertwining of our history and traditions that I encountered in Norwich through evensong, Mass and Julian, and in Walsingham through both Shrines and the Pilgrim’s Way between the two, shows that those of us who look to God, follow Jesus, seek the guidance of Our Lady and work for peace, justice and reconciliation in the world must walk and work together.

Throughout this little Norfolk pilgrimage, my literary companions in my suitcase, beside Julian of Norwich’s Revelations, included Joseph Pearce’s brilliant Catholic Literary Giants, Humphrey Carpenter’s The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, Iain Dale’s Kings and Queens and a biography of St Charles Borromeo. I also read one or two of Christina Rossetti’s poems each day.

The others on my pile – Rowan Williams’ Passions of the Soul, St Gregory the Great’s The Life and Miracles of St Benedict, Malcolm Muggeridge’s A Third Testament, Austen Ivereigh’s First Belong to God: On Retreat with Pope Francis, Pope Benedict XVI’s Great Christian Thinkers, Michael Walsh’s The Jesuits and Jan Morris’ Oxford – will have to wait until later in Lent or beyond.

Pearce’s book was absolutely gripping, a wonderful journey through Catholic writers, largely dominated by G.K. Chesterton, Hilaire Belloc, Evelyn Waugh and J.R.R. Tolkien, with people like Maurice Baring, Siegfried Sassoon, Graham Greene and others making appearances. As I journeyed around Norwich and parts of Norfolk, discovering parts of my own country I had never visited before, Pearce’s musings on Chesterton, Belloc, Waugh, Tolkien and the others provided riveting company.

I have been engaged, in various capacities, in human rights advocacy for over 30 years. During those years at least two of my friends have been assassinated, others have survived attempts on their lives and many others live with daily death threats. Many of my friends are in prison.

The murder of Alexei Navalny – which happened just hours before I embarked on this retreat – was a reminder to me that some of my friends could still die in prison. I had the privilege of knowing Russian dissident Vladimir Kara-Murza, a British citizen now serving 25 years in Vladimir Putin’s gulag. I have already mentioned Jimmy Lai. The family of Myanmar’s democracy leader Aung San Suu Kyi’s are friends of mine, and I have had the honour to meet her on several occasions, yet she may well not see freedom again. Churches, shrines and cathedrals across Norwich and Walsingham have been inundated with prayer cards and candles invoking requests for intercession for these friends and others.

I have been deported from Myanmar twice, denied entry to Hong Kong once, chased by the police in northern China, missed a bomb by five minutes in Islamabad and stared evil in the face in North Korea. What I have experienced pales into insignificance compared to what Navalny, Lai, Suu Kyi or others face, but it gives me some tiny taste, and an ability to empathise.

After a while, as passionate as I am about this cause and as invigorating and inspiring as this work can be, it gets a bit exhausting. And so regular breaks – whether it is keeping week-ends free, taking a day off here and there, ensuring a good holiday a few times a year or going on retreat, or some combination of these – are vital.

And it is when taking such breaks that one realises the importance of unity among those who have common cause, and the importance of persistence.

Two street names stayed with me from this adventure. The first is the fact that Norwich’s Catholic cathedral – of St John the Baptist – which is the second largest Catholic cathedral in the country after Westminster’s, is situated on “Unthank Road”. That seems a peculiarly inappropriate street name. I am not sure if there is a pun intended, but I’d like to rename that street “Thankfulness Road”. There is much that is wrong in the world today – but there are still things for which we can and should thank God.

The second is that the Anglican shrine in Walsingham’s address is Common Place. That seems an altogether better address.

Let us all find a common place in which to unite – and give thanks, as we renew our faith, our determination and our fight.

Benedict Rogers is a human rights activist and writer. He is the co-founder and chief executive of Hong Kong Watch, a senior analyst at CSW, author of three books on Myanmar, a personal memoir – From Burma to Rome: A Journey into the Catholic Church (Gracewing, 2015) – and most recently The China Nexus: Thirty Years In and Around the Chinese Communist Party’s Tyranny (Optimum Publishing International, 2022).

Loading ...

Loading ...

What do you think?

You can post as a subscriber user ...

User comments (0)