As regular readers of these columns might have guessed, I’ve a bit of a thing for medieval saints. Sooner or later, anyone with more than a passing interest in medieval hagiography, history, art history or theology will need to consult the Golden Legend (Legenda aurea in the original Latin).

This anthology of saints’ lives and accompanying commentary on the major feasts of the Christian year was compiled by Jacobus de Voragine, an Italian Dominican friar, in about 1260. It was a medieval bestseller. But who was Jacobus? Why did he write this work? How can its extraordinary popularity be explained? And what caused the Golden Legend to dramatically fall from favour in the sixteenth century?

None of the answers are exactly straightforward and even his name requires some explanation, being a Latinised version of his Christian name – Jacobo – and place of birth – Varazee, a small town near Genoa in Lombardy. Jacobus was born in c.1230 and joined the Dominican Order at the tender age of about 14. Founded by St Dominic just thirty years earlier, this Order (also known as the Order of Friars Preacher, or the Blackfriars because of the colour of their outer cloak) was an intellectual powerhouse of the medieval Church and its bulwark against heresy.

Jacobus’s talents were such that he quickly rose to prominence among the Dominicans’ learned ranks. Jacobus’s crowning achievement was appointment in 1292 as bishop of Genoa, an office he occupied until his death in 1298. His episcopal rule of Genoa was characterised by love for the poor and peace-making between rival noble factions. No surprise, therefore, that the Genoese venerated his as a saint.

The erudite Jacobus was also a prolific preacher and author, his output including collections of sermons and a history of his beloved Genoa. But he is most famous today for his writings about the saints and the sacred.

The mid-thirteenth century, when Jacobus composed his anthology of hagiographies, was a time of great ecclesiastical reform. At the core of these changes was the strengthening of the pastoral care of the laity and the quality of the parish clergy. Preaching and catechising were central to these efforts and the Golden Legend was most likely compiled to assist Jacobus’s brother Dominicans and parish priests in such tasks.

The fact that it was written in Latin, the language of the medieval Church, further indicates its intended clerical audience. The book’s original title was Legenda sanctorum, or Readings on the saints. Each of its 200-plus chapters is devoted to an individual saint or Christian festival, especially the feasts of Christ and the Virgin. The book starts with Advent (then, as now, the beginning of the ecclesiastical year), the subsequent chapters following the rhythms of the Church year.

The saints and holy days deemed worthy of inclusion were, for the most part, the “official” saints and feasts of the thirteenth-century Church, and would therefore have been encountered in liturgical calendars from across medieval Europe. That being said, the reader is left in no doubt of the author’s patriotism for his native Lombardy. The penultimate chapter, ostensibly a Life of Pope Pelagius I (r.556-61), turns into an extended dissertation on the history of the Lombards. Indeed, an alternative title for the Golden Legend was The History of the Lombards.

The individual biographies for the saints are somewhat formulaic and, I have to be honest, can be a bit of a hard slog. They typically start with an often-fanciful discourse on the etymology of the saint’s name, showing that, through nominative determinism, the person was destined for sanctity. The saint’s various holy deeds, miracles, and in many cases grisly martyrdom are then recounted. Apparently, 81 different methods of torture, mutilation and painful death are described. It’s not a book you’d want to fall into the hands of tyrants or the criminally insane.

Jacobus’s sources encompassed the Bible and Apocrypha, early Christian Fathers such as SS Ambrose, Athanasius and Augustine, medieval theologians and thinkers like St Bernard of Clairvaux and earlier assemblages of saints’ lives.

The book was an immediate success and was widely disseminated, even during Jacobus’s own lifetime. It quickly assumed the name by which its known today, the Legenda aurea or Golden Legend: its contents were quite simply considered worth their weight in gold. It’s also worth emphasising that “legend” had none of the negative associations of today and then simply meant reading aloud.

Anyone tempted to indulge in a moment of Monty Python-esque snobbery of chronology, mocking Jacobus and his audience for their credulity and superstition, will be surprised to discover that on more than one occasion the author raised his literary eyebrow when recounting the more colourful deeds of the saints. For instance, he states that the story describing how St Margaret of Antioch, one of the most popular saints of the Middle Ages, survived being swallowed by a dragon and burst from its stomach, “was apocryphal and not to be taken seriously”. But overall, the Golden Legend was very much a work of its time: a mirror reflecting the beliefs and preoccupations of thirteenth-century Catholicism.

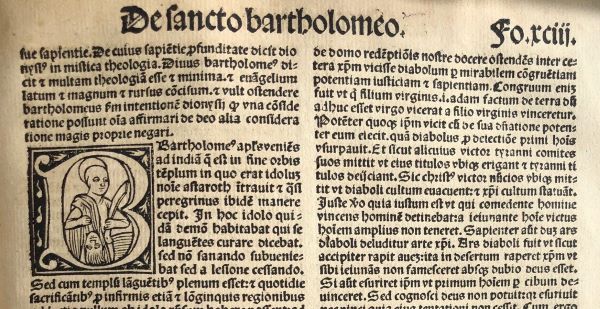

And that ensured its success. The medieval popularity of the Golden Legend is shown by the survival of over 1000 manuscript copies. It was translated into most of the major European languages, the earliest surviving English version dating to 1438. The invention of printing in the mid-fifteenth century only added to its fame. Between 1470 and 1500, over 150 editions rolled off the presses, many adorned with woodcuts illustrating the saints’ pious deeds and bloody deaths. William Caxton printed an English translation in 1483, the first of nine such editions, the last appearing in 1527.

But by then this quintessential work of medieval hagiography was already falling out of favour. High-minded humanists (in the Renaissance, not Richard Dawkins sense) regarded the Golden Legend with disdain. It just didn’t come up to their scholarly standards which were founded on a rigorous revaluation of Biblical and early Christian texts. “How unworthy of the saints…is that history of the saints called the Golden Legend”, wrote Luis de Vives (d. 1540). “I cannot imagine why they call it golden when it is written by a man with a mouth of iron and a heart of lead.” The harshness of this judgement speaks volumes about this age of Catholic and Protestant Reformation.

Interest in the Golden Legend revived in the nineteenth century when it chimed with romantic notions of the Middle Ages. Historians and art historians began plundering it as a sourcebook, as they do to this day. I’m among them: a well-thumbed modern translation rests on my bookshelves. Perhaps more unusually, I also have a Latin edition printed in Lyon in 1509.

It’s not a book I regularly read (it’s much easier to consult the translation), prizing it instead as an historical artefact and enjoying it for its woodcut initials. And it says something about the late medieval popularity of the Golden Legend that 500-year-old copies are readily affordable to the likes of me.

Loading ...

Loading ...

What do you think?

You can post as a subscriber user ...

User comments (0)