A ban on public celebration of the liturgy, restricted access to the sacraments, and special arrangements for the burial of the dead. No, I’m not referring to the closure of churches and other places of worship because of Covid-19. Early 13th-century England and Wales witnessed curtailments of religious observance that were every bit as extensive as the emergency regulations that have been very partially eased this week. What’s more, the application, mitigation and ultimate lifting of limitations on worship 800 years ago were every bit as uneven, piecemeal and confusing as anything we’ve experienced during the lockdown of 2020.

In the popular imagination, the Middle Ages are associated with dirt, squalor and mass mortality caused by epidemic disease. But the sweeping restrictions on priestly activity in the early 1200s weren’t because of a visitation of the Pestilence (the Black Death wouldn’t arrive for another century or more).

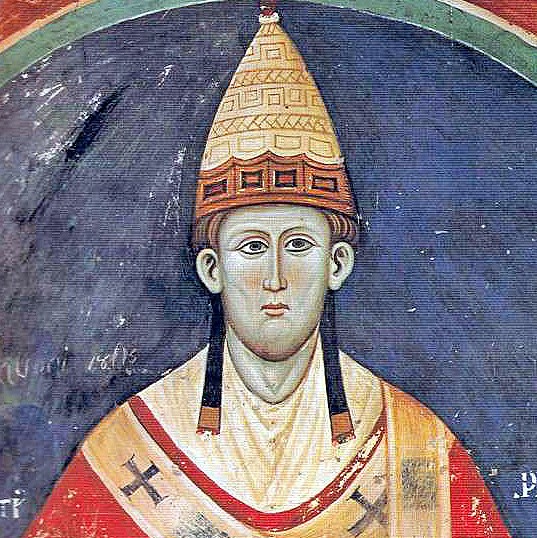

Rather, their origin lay in a bitter spat between King John and Pope Innocent III over the appointment of the archbishop of Canterbury.

Under papal guidance, Stephen Langton was elected to the see of St Augustine (Canterbury) in 1206. But King John was having none of it, angrily asserting that no bishop could be consecrated in England and Wales without the explicit consent of the Crown. There was no way that the Pope was going to agree to that.

Events rapidly escaladed. John forbade Langton to land in his realm. This prompted Innocent to deploy the ultimate weapon in the papal spiritual arsenal: in March 1208, John’s kingdom was placed under an ‘Interdict’ - a clerical lockdown.

The terms of the Interdict were deliberately far-reaching and severe. They extended to both the guilty King (who was also under sentence of excommunication) and his subjects. Innocent was fully aware that the latter had done nothing wrong. But the hope was that John would be forced by the collateral spiritual damage inflicted on the populace to come to heel and accept the authority of the Pope.

Religious life was pared back to its bare essentials. The only permissible sacraments were baptism and the Last Rites, the minimum needed to offer any hope of spiritual salvation. Celebration of the Mass was prohibited, so too the ordination of the clergy. The dead were denied burial in consecrated ground, and were instead interred in makeshift un-blessed burial plots. Church bells fell silent.

But from the outset there was confusion about the precise terms of the Interdict

For instance, were newborns to be baptized at home, or was it permissible for baptism in parish churches with only the priest and godparents present? And given that the consecration of holy oil wasn’t allowed, what should be done when supplies were running low? Was it ok to dilute the ever-diminishing stocks with holy water?

Just like now, some assumed that the restrictions were for other people. The austere Cistercians believed that their special papal privileges exempted them from the Interdict and therefore carried on much as normal. Innocent rapidly slapped them down. The white-clad monks were left in no doubt that the Church, all all its parts, were in this together.

There were also some loopholes. Services with a congregation were a strict no-no, but it was ok for clerics to say their hours in private. The portals of great monastic churches were slammed shut, though pilgrims were allowed to use more ‘secret’ (or side) doorways to enter and venerate relics.

Nor were the restrictions entirely logical. Confession was encouraged but without its essential element, the comforting words of absolution.

Innocent was sadly mistaken if he thought the Interdict would force John into rapid compliance. Instead, the King defiantly hit the Church where it hurt, confiscating the estates of prelates who wouldn’t celebrate the liturgy.

John also ordered the locking up for ransom of the ‘mistresses, housekeepers and lady-lovers’ of numerous naughty priests. This action simultaneously embarrassed the offending clergy while also denying them the (admittedly illicit) comforts of human company and intimacy. Some monastic authors did their best to ensure that the guilty clerics were suitably shamed for their transgressive behaviour.

Yet despite all this, priests and laity across the land did their best to and adhere to the Interdict’s terms. There’s no evidence of mass disobedience. The ecclesiastical authorities continued to conduct whatever activities remained permissible: the building of churches continued, priests announced feast days, holy water was distributed in churchyards.

The severity of the Interdict was gradually eased. In 1209, ‘conventual’ churches were permitted to celebrate a weekly Mass behind closed doors. But this led to allegations that some parts of the Church were being singled out for special favour: why should religious communities, but not the laity, be allowed the Mass and the opportunity of Holy Communion? Moreover, if you’re not quite sure what makes a church ‘conventual,’ then you’re in good company as there was considerable uncertainty about the definition, even at the time of the Interdict. Less controversially, provision of the Last Sacrament to people on their deathbed was officially sanctioned.

It couldn’t last forever. After six gruelling years of more or less closed and silent churches, Pope Innocent formally lifted the Interdict in July 1214. But even then, it wasn’t because the underlying cause had been satisfactorily resolved. Rather, political and economic expediency had forced King John to give in and accept Langton as Archbishop of Canterbury, because he needed papal backing to help face down the twin threats of rebellious barons at home and a French invasion fleet.

King John ended up with the worst of all worlds: not only did he capitulate to the Pope but his grip on power rapidly disintegrated. Let’s hope that our lockdown comes to a speedier, more satisfactory and consensual conclusion.

Loading ...

Loading ...

What do you think?

You can post as a subscriber user ...

User comments (0)