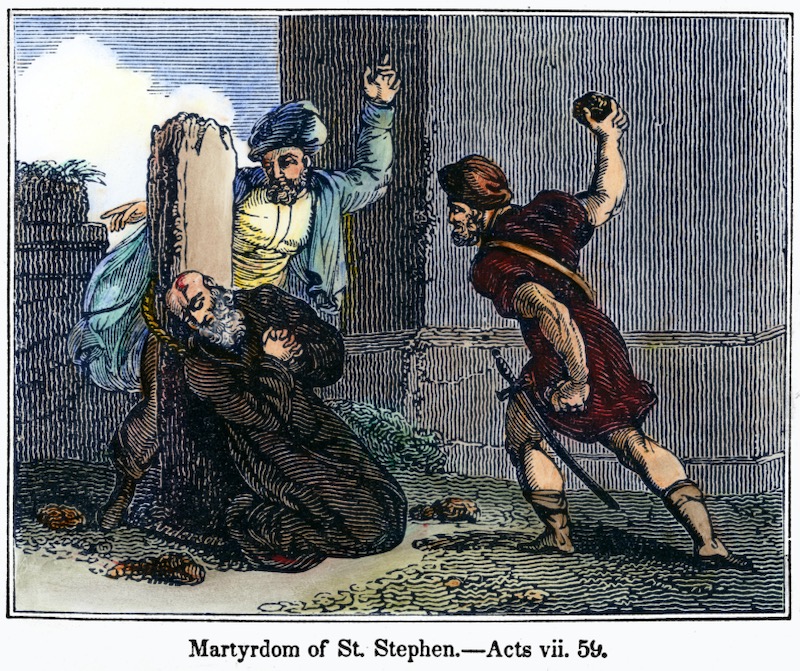

It may at first seem strange that today’s readings on the last Sunday of Eastertide include accounts of both the first Christian martyrdom, the stoning to death of St Stephen, and the outbreak of the first persecution of Christians, both aided and abetted by the zealous Saul, later to become Paul.

Equally significant is the choice of the Book of Revelation for the second reading, the last book of the New Testament, written during a time of vicious persecution, possibly under the emperor Nero, more probably Domitian, offering encouragement, consolation and hope to the beleaguered Church in a time of terrible tribulation.

Until this Sunday, attention has been focused on the successful spread of Christianity around the Roman world, from Jerusalem to the very heart of Empire, Rome, the Eternal City. But turning our attention to martyrdom and persecution as we leave Eastertide is a salutary reminder that the planting and flourishing of Christian faith did not take place without the witness of Christians suffering out of love for Christ. Stephen’s martyrdom is a potent reminder that the core witness is not our words, but our living and, indeed, our dying.

The second-century African theologian, Tertullian (160-225AD), has it in his Apologeticus (197AD) that the blood of the martyrs was the seed of the Church. A much later and more gentle reminder that what we are and do matter more than what we say, is given in the early 14th century Fioretti di San Francesco, where it’s recounted that on one occasion, Saint Francis took the young Friar Juniper with him to preach in and around Assisi.

When they returned without having uttered a word, the puzzled young friar asked St Francis why they hadn’t preached, as intended. He replied that they had indeed been preaching, from the moment they left to the moment they returned.

In the Acts of the Apostles, Peter and Paul and others speak of themselves in their preaching as ‘witnesses’ to the resurrection. But by the middle of the second century, that word would be used explicitly and almost exclusively for those whose witness led to the shedding of their blood, as it would in due course for both Peter and Paul in Rome. μ?ρτυρας became our word ‘martyr’ and the martyrs would become the first Christians to be revered as ‘saints’, who, in their heroic imitation of Christ, had forged the closest possible identity with Christ in his own self-sacrificial death.

It was that identification that gave rise from the earliest times to the practice of celebrating the Eucharist on the tombs of the martyrs, continued still in the custom of placing martyrs’ relics in the altar. And it was that close association of martyrdom with the Eucharist that prompted many of the early (and much later) martyr-priests to kiss the scaffold on which they were about to be executed, just as they kissed the altar on which they were about to celebrate Mass. As we identify ourselves with Christ in his self-offering in the Mass – “This is my body, which will be given up for you” – so even more explicitly they in their martyrdom, their last Mass, identified with his supreme act of love on the Cross.

And this is key to understanding martyrdom, so ambivalent a notion in the modern world, widely regarded as it is as either an expression of intolerance or the tool of terrorists or the pathological glorification of pain. Christian martyrdom is the supreme act of witness because it is the supreme act of love, not sought for its own sake, but endured where unavoidable out of love. Martyrdom witnesses to Christ’s own love, manifest in his readiness to accept the consequences of becoming human, fully human, which is to say fully loving, in a world fashioned by fear, violence, rivalry and the abuse of power – the opposite of love, in other words.

It is not dying, as such, that is the supreme witness, but the love that accepts death as its price. We were redeemed not by Christ’s death, per se, but by the divine love which led to his death at our hands. “We know love by this, that he laid down his life for us.”

For every one of us, too, selfless love is the only authentic witness to Christ; and, though it may or may not cost us our lives, it will always be costly. But, like all the other virtues, it is its own reward because love is life itself. Without love we are dead. “Whoever does not love abides in death.” It was God’s love that gave us life; and in becoming a human being, it was his love, enduring all that being human entailed, that brought us to life again, by sharing with us his own, eternal life. That is what is meant when it is said that ‘Christ died for our sins’. Jesus promised that “…the Spirit of truth…will be my witness: and you, too will be my witnesses”.

The Spirit, in other words, will witness in and through us. For it is the Spirit, the mutual love of the Father and the Son, that empowers us to love as God in Christ loves, and so, by the gift (and gifts) of the Spirit, be his witnesses, even if it costs us “not less than everything”.

Loading ...

Loading ...

What do you think?

You can post as a subscriber user ...

User comments (0)