The first four verses of today’s gospel in the original are just about the most elegant Greek of the whole New Testament. Coming at the very beginning of Luke’s gospel, they indicate beyond doubt that the author was an educated and literate individual, who chose his words carefully and paid close attention to style. They also show that he was well-connected and familiar with the formalities of officialdom. So, for instance, he addresses his reader – and possibly his patron – as Most Excellent, the normal address for a high-ranking Roman official.

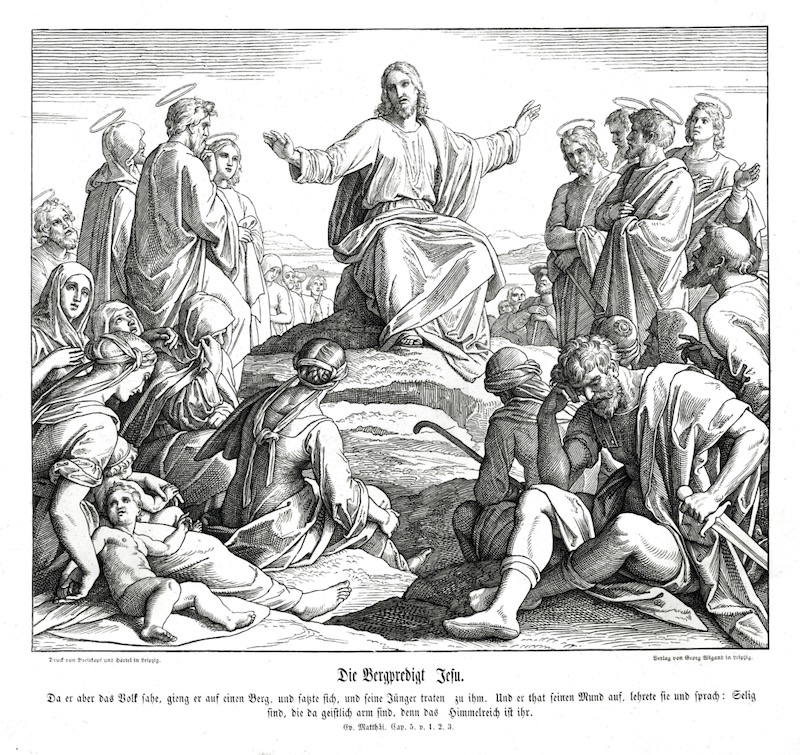

But literate, educated and well-connected as its author was, Luke’s gospel, for all its elegance, is in many ways the hardest hitting of the four. For instance, where Matthew’s beatitudes begin with the more nuanced, “Blessed are the poor in spirit”, Luke’s version states baldly, “Blessed are the poor”, full stop.

Again, he makes no bones about the chief cause of conflict between Jesus and the religious establishment: in his view, prejudice, pettiness, and pride had turned the broad and generous provisions of the Mosaic Law into a straitjacket, confining those who were “in” and damning those who were “out”. Luke is clearly writing for the latter. Little surprise, then, that his second volume, which we now know as the Acts of the Apostles, charts the breaking out of the Gospel from its Jewish origins to become Good News for every nation and every race under heaven.

It’s also significant that there are more allusions in Luke’s gospel than in any other New Testament text to worldly markers and reference-points. Each of the first three chapters of his gospel, for instance, opens with just such a secular reference: “In the days of King Herod of Judea”; “Now at this time Caesar Augustus issued a decree”; and “In the fifteenth year of Tiberius Caesar’s reign”. But in each of these chapters, immediately after making these grandiose references, Luke switches his attention to individuals of no worldly significance at all: a barren woman, an ageing couple, an unmarried, pregnant village girl and a desert-dwelling eccentric.

So, even at this early stage of his gospel, Luke clearly intends to challenge his readers. In particular, he asks us to reconsider where the centre of things really lies and to ask ourselves where we locate ourselves in relation to that centre. In particular, he asks us to examine whether we too draw boundaries between those who we think are “in” and those we think are “out”. This consideration sets the pattern for the whole of his gospel. In his narrative, those who play the central roles are all outsiders, either outside the recognised structures of respectable, tribal or patriarchal society on account of being childless, widowed or unmarried, for instance; or the sort of people who’ve excluded themselves, by their profession or behaviour or both: tax collectors and prostitutes, for example.

It’s these, in Luke’s understanding, who are the ones to whom Jesus, as he implies in the quotation from Isaiah, has been sent: “The poor, the downtrodden, the blind and the captive.” According to Luke, it’s not the rulers and leaders of this world or the rich and powerful who are to be lifted up by God, but those who, from the world’s point of view, have no part to play in the way the world works. Hence, Luke puts at the centre of his account individuals who, according to conventionally pious expectation, could never enjoy either the world’s or God’s favour.

That reversal is the common theme running through the three great songs of these early chapters of Luke’s gospel – that of Mary in the Magnificat, Zechariah in the Benedictus, and Simeon in the Nunc Dimittis. And throughout the rest of his gospel, Luke depicts Jesus repeatedly clashing with all those whose position is threatened by his sympathy for the outsider in their midst: as, for instance, when the sinful woman gatecrashes the Pharisee’s dinner, or the greedy collaborator, Zacchaeus, unexpectedly and, to the Pharisees, unacceptably, plays host to Jesus. Luke makes the same point in his powerful parables of loss and return, such as the parable of the Prodigal Son. In each, he shows that those who believe that they’ve put themselves beyond the reach of God’s love and mercy, turn out to be closer to God in their hearts than anybody else. And, in common with the other gospels, Luke makes it abundantly clear that, as a matter of fact, these were the kind of people whose company Jesus personally preferred.

That observable fact alone carries huge significance. But we’d make a great mistake if we inferred from this that, in Luke’s account, the outsider replaces the insider, as if Jesus were advocating some sort of primitive socialism or barmy bohemianism or, much less, social iconoclasm. No, Luke is endorsing neither moral lassitude nor moralising superiority. And he’s certainly not debunking legitimate authority or denigrating devotion. He’s not suggesting, for instance, that Jesus loves the sinful woman more than the Pharisee; or that the rogue Zacchaeus is more favoured by God than the religiously observant who complain about the company he keeps. What he’s teaching is that it’s God’s view that matters, not ours: what we are before God, is what we really are, nothing more, but nothing less, as St Francis says in one of his Admonitions.

He’s overturning, in other words, the ingrained habit we all have of judging others and even ourselves on the false premises of power, status, achievement, or adornment. It’s precisely that tendency, usually borne of deep and unacknowledged insecurity, that inexorably creates the outsider. But most uncomfortable of all: Luke is teaching us, as does Matthew in that terrifying parable of the sheep and the goats at the end of his gospel, that whenever and however we consciously exclude anybody from human warmth, respect and esteem, and even more, when we persecute them for not being “one of us”, we’re excluding and persecuting God. That was precisely what Saint Paul so painfully discovered on the road to Damascus. Whenever we consciously, even if only interiorly, consign anybody, on any grounds whatever, to the role of outsider, we are making God an outsider. And how mad is that?

Loading ...

Loading ...

What do you think?

You can post as a subscriber user ...

User comments (0)