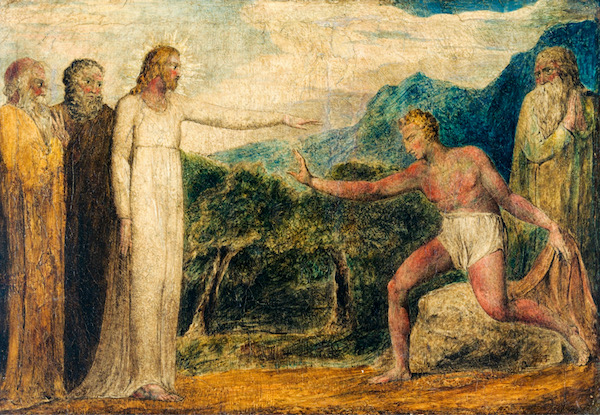

Bartimaeus, the blind beggar, is one of only a handful of people Mark names in his gospel. He even tells us the name of his father. That alone should alert us to the significance he attached to this episode, the last of Jesus’ miracles in Mark’s account. It forms a mini climax to his narrative, bringing together many of its principal themes.

Significantly, it comes at the end of a long section that began with the healing of another blind man, this time un-named. And in between these two restorations of physical sight, Jesus has been trying, with little success, to cure the spiritual blindness of his closest followers, the disciples. But the healing of Bartimaeus is much more than a miracle story: for all its raw immediacy, it is an intriguing and subtle dialogue about the meaning and consequences of faith. Bartimaeus may be without physical sight, but he possesses prophetic insight in abundance. Yet again, Mark points to an outsider, someone without status, position, or possessions, as a model of faith.

He is drawing, of course, an uncomfortable contrast between the blind, deprived beggar, and his own disciples. Mark drives that painful contrast home by having Jesus ask the blind man the same question that he’d asked James and John a little earlier, when they had shamefacedly sought positions of power and influence. Precisely the same construction and the same words are retained “What would you have me do for you?” James and John had asked him in last week’s gospel for glory; blind Bartimaeus asks him for sight, contrasting his humility with their arrogance. The blind beggar’s acknowledged helplessness, in other words, enables him to see more clearly than the two disciples, who are blinded by venal ambition and hunger for power.

All of this is conveyed in the detail of the encounter: Bartimaeus’s actions are those of a desperate man who knows that Jesus’ passing by is his one and only chance to recover his sight; and nothing is going to deter him from approaching him. The casting off of his cloak, in his indigence his most prized and most needed possession, is a powerful and vivid expression of faith.

Trusting that he will be cured, he sets aside all other needs, in order to reach Jesus. What emerges from his dialogue with Jesus is not that he believes because he’s healed, but rather that he’s healed because he believed. As on so many other occasion, Jesus tells Bartimaeus that his faith has healed him. His faith, like all faith, is, of course, a gift of God; and it was faith that afforded him insight into what he needed most and assured him where and how that need would be met. Faith enabled him to know that Jesus would not refuse him what he needed most. (God often gives us, not what we ask for because we think we that need most, but what we really need most and would have asked for had we known. Often prayer teaches us what we really need and want.)

Mark clearly thinks that the disciples – and, by implication, we – have much to learn from the blind beggar. And we do. Only knowing what we need most, as did Bartimaeus, renders us receptive to the gift of faith. And, as with Bartimaeus, faith consists, first and foremost, in knowing and trusting that we are loved unconditionally, that nothing we do can ever stop God loving us; and knowing that God always answers our prayers, albeit often in ways we don’t at the time recognise. Of course, we articulate what we believe in language, in words and propositions. But the object of our faith isn’t, ultimately, those propositions: the object of our faith is what 3 they seek, inevitably inadequately, to express.

The object of our faith is God, who is beyond all propositions, language and thought. Everything that we profess in faith is a way of saying that we believe in God; and saying that we believe in God is saying that we believe in God’s love, because He is love. Though God’s existence and God’s love can be formally distinguished – we can be convinced that the world doesn’t account for its own existence, from which we infer that there is something that does, namely God – we don’t, in practice, arrive, first, at the conviction that God exists, and then, discover that he loves us. It’s precisely God who is Love Itself, who reveals himself to us.

To have faith, then, is to believe that there exists a love that will never be withdrawn and to set our hearts on that love, which is God., the source of the love that we experience here and now and the source of that desire for a love that will never end that is written into our very nature. To live here and now in the presence of that love, God, is what it means to live in faith. To live endlessly in the presence of that utterly fulfilled and utterly fulfilling love, is what it means to live in Heaven.

Loading ...

Loading ...

What do you think?

You can post as a subscriber user ...

User comments (0)