The Passion of Christ, read on Palm Sunday today, and again on Good Friday, carries us into the heart of the mystery we call God, the mystery of our Creator’s unbounded love for the whole of his creation, from the infinitesimal elementary particles that constitute the whole of material reality around and within us, to the vast infinity that stretches into the endless unknown distance of time and space beyond us.

And, even more wondrous, for each one of us, for you and for me: minute in scale, momentary in duration: “This Jack, joke, poor potsherd, patch, matchwood, immortal diamond…” made and destined to share in the endless life and infinite love of our Creator.

“God loved the world so much”, St John tells us, “that he gave his only Son, so that everyone who believes in him may not be lost but may have eternal life.”

Nevertheless, hearing the Passion should also unnerve us. It is unnerving to remember that Jesus met his death not at the hands of criminals, terrorists or the deranged, but people trying to avoid trouble, for themselves and for the institution they served: people, doubtless, much like most of us, not distinguished for either heroic good or gross evil.

If his death had been engineered by obviously bad people, viciously intent on doing him harm, it would be easier to distance ourselves, easier to feel unimplicated. But no such distance exists. They were pragmatists, putting the needs of an institution before the good of an actual flesh and blood person: and thereby, also, saving their own skins. His discomfiting presence threatened both their sincerely held certainties and their jealously guarded self-interests. And so they had conveniently decided he was not “one of us”.

Who knows how we would have acted (or reacted) in the same situation? What price would we have been prepared to pay to keep ourselves out of trouble, to retain the regard of those we respected and the popularity of our peers? But even more disconcerting is the fact that those who conspired to bring about Jesus’ death were seeking to preserve specifically religious rectitude and purity. They were the appointed guardians not only of order and decency, but piety and religious observance: a fact that should prompt painfully searching questions for all of us.

How often have I acted for “good” reasons that were at variance with my “real” reasons for doing what I did? Or how many of my actions, honestly undertaken for the good and in accord with my understanding of “God’s will”, might in fact turn out to have been contrary to that will, a figment of my deluded self-righteousness or fainthearted reluctance to listen to the views of other and even change my mind?

The uncomfortable truth is that the tragic actions of those who brought about Jesus’ death prefigure the sins and failures of all of us throughout human history, from the most horrendous, stomach churning, public evil to the myriad concealed subterfuges and hypocrisies engaged to avoid trouble or save face or simply to secure a quiet, untroubled, prosperous existence, inwardly reassuring ourselves that this has nothing to do with us.

But, at the same time, the infinitely comforting truth is that his death absorbed even the very worst that we have, can or will ever do: he, we believe, bore all our faults and shouldered all our sins on his Cross. And just as those who brought about his death were unknowingly instrumental in bringing about our redemption, so God will, as only God can, bring unimaginable good out of all the pain and anguish caused in this world by human folly - our folly.

His Cross reassures us of that: it was, after all, both the greatest evil and the greatest good. So, as Holy Week unfolds, we should remember that we are not mere spectators but participants.

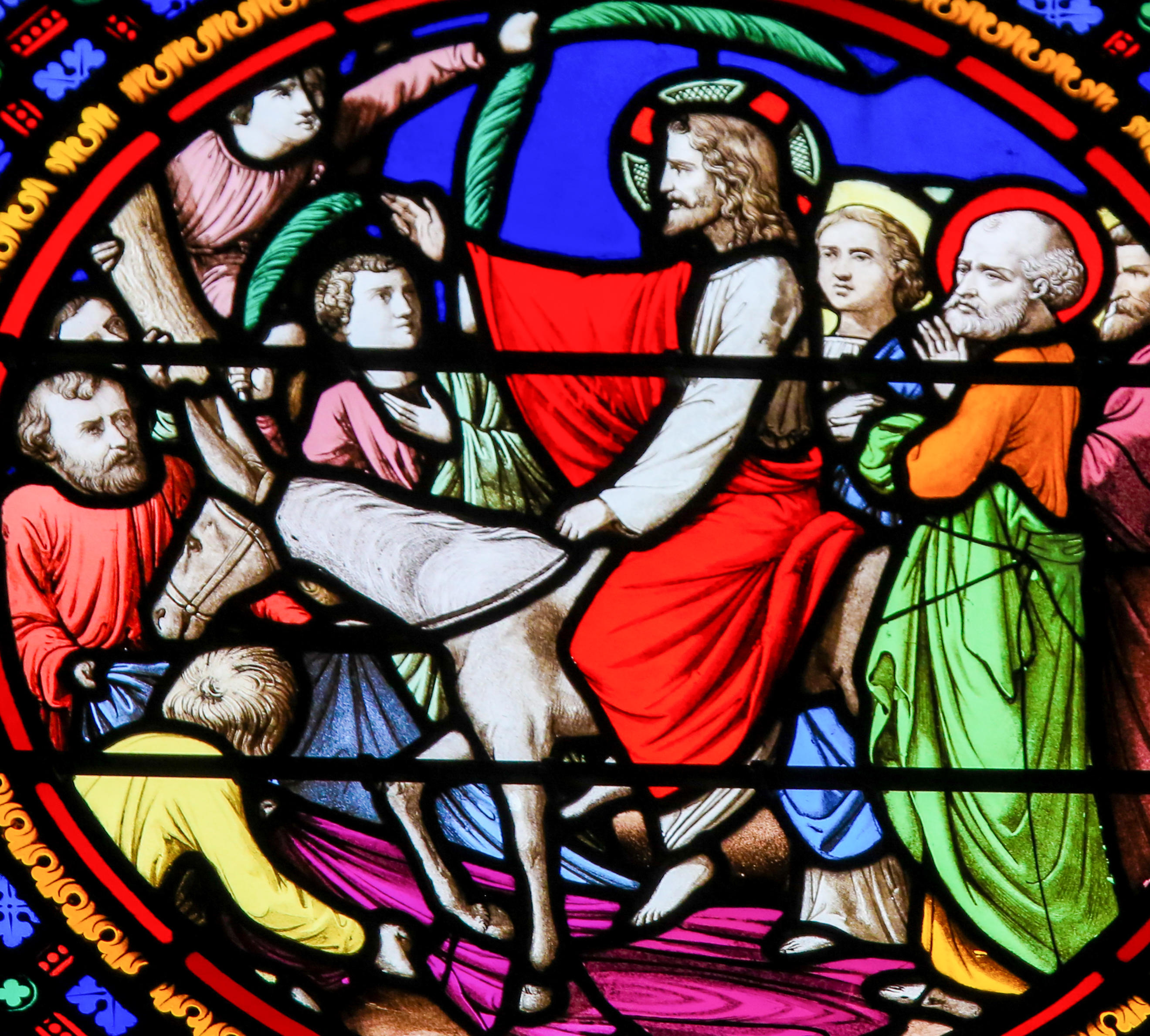

We are among the cheering tumult in Jerusalem on Palm Sunday; in the upper room, celebrating Passover with him on Maundy Thursday; witnesses on Calvary, alongside his mother, Mary, on Good Friday; experiencing the same silent sense of loss on Holy Saturday; and with Mary on Easter Morning who, in the garden where his lifeless body had been laid, recognises her beloved, unchanging friend, Jesus, when he utters her name.

We should remember as Holy Week begins, that we’re contemplating not an end but a beginning: a death, certainly, but a death that was uniquely life-giving. In St Thomas the Apostle’s heart-rending words to his fellow-disciples, as they turn towards Jerusalem: “Let us go also, then, that we may die with him.” For, as St Paul says, “If we have died with him, we shall also rise with him.”

Loading ...

Loading ...

What do you think?

You can post as a subscriber user ...

User comments (0)