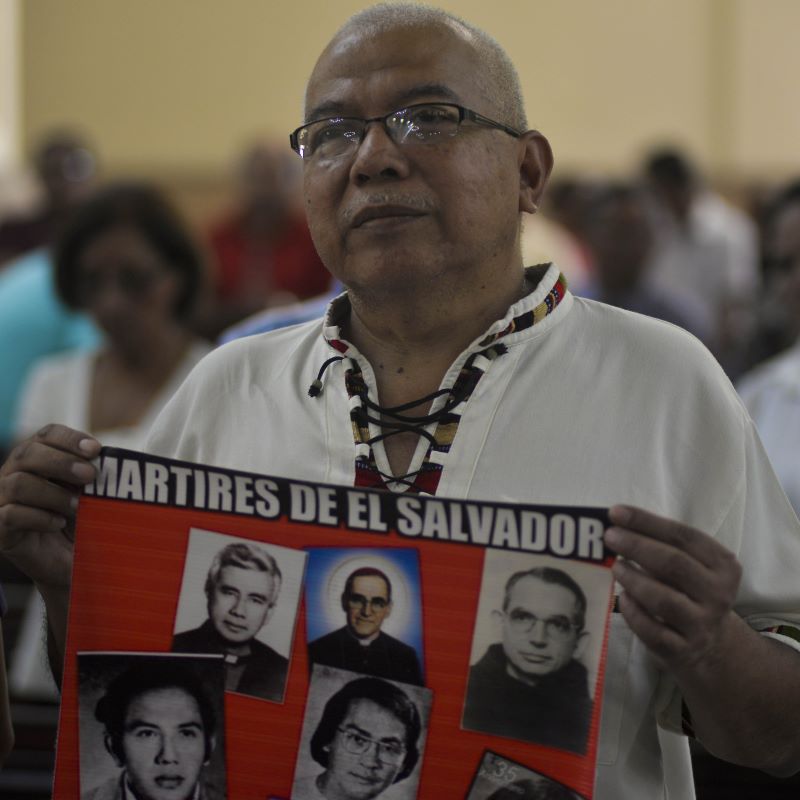

On 24 March, the anniversary of the Saint Oscar Romero's martyrdom, the Church celebrates his feastday. Many Catholics were marking the anniversary long before Romero's canonisation in 2018. Here is the sermon which Herbert McCabe OP preached at Blackfriars, Oxford, on the 24th of March 1989, at a Mass in memory of Romero. The gospel reading was Luke 24:1-10 (Luke’s account of the first Easter morning).

When the Brazilian Dominican Frei Betto was in prison one of his interrogators asked him: "How can a Christian collaborate with a communist?". He answered: "For me, men are not divided into believers and atheists but into oppressors and victims". I think this was a witty reply-it certainly wasn’t saying anything so tedious as "Truth doesn’t matter; let’s do something practical". I think it was witty because it turned the interrogator’s question round in a new and surprising way, and because it challenged and disturbed his interrogator: "Is it worse to collaborate with atheists as I do or to collaborate with injustice as you do? When I work with atheists I do not become an atheist; but when you work for the unjust you do become unjust".

Frei Betto was saying that it is just because he passionately thinks that truth matters and just because he is not an atheist, that his first concern is not whether people agree with him but whether they are suffering and in particular suffering at the hands of sinful men, from the lovelessness and injustice of others. His atheist comrades may have their own reasons for struggling against injustice, but for him his reason is his belief.

His belief is that God so loved the world that he sent his son, not to set the world to rights but to be one of us; not to rule the world but to suffer at the hands of the unjust and to suffer out of love, out of protest against the oppression of his beloved, to be a victim because he refused to collaborate with the domination of others. In doing this, by his acceptance of the cross, Jesus released in us, in will those who did not reject him, power from within us by which we may begin to set the world to rights.

This power is greater than all technical power, greater than the power of all the guns and bombs and torture instruments that men have made. It is the power which made men. It is the Holy Spirit. This power comes from unfathomable depths within us where God’s love is making us; it is God’s love, God’s spirit, welling up through us. This is the power, says St John, that overcomes the world, our faith: our recognition of God’s love within us and working through us to transform the world. This is the power that Paul calls the weakness of God, the weakness of God tortured, crucified, killed out of solidarity with all who suffer; this is the weakness of God that is stronger than all the power that human beings can wield over each other.

It is from the cross that our victory comes, and the name of this victory is resurrection. Luke’s story of the resurrection that we read tonight is identical with the other gospel accounts in two respects: firstly, it is the women who discover the victory which is the meaning of the cross, and secondly, it begins with loss, with absence, with desolation. The women because they were supremely the symbol of those forced into dependency-not necessarily poverty or suffering, certainly not in the Jewish world dishonour, but dependency.

When the prophets find a phrase for the most needy in society it is the "widow and orphan", those without a man on whom to depend. It is, I think, because women symbolise dependency that they play such an important part in the New Testament, where all the conventional values are reversed.

And in another and more fundamental reversal what they discover is not the return of Christ in power but his absence: an empty tomb. This, the gospel is saying, is the beginning of faith, of real faith: to recognise the emptiness, the absence of the power of Christ in this world. Frei Betto’s interrogator, for all I know, was what is called a ‘good Catholic’. If so, he knew where Christ was: in the Blessed Sacrament, in the power of the priest, in the sacramental structure of the church and its authority. But all these beliefs are just caricatures of the Catholic faith if they do not spring from a fundamental recognition of absence-what Jesus called a ‘hunger and thirst’, a desire for what is not there, a hunger and thirst after justice, a hunger and thirst for the kingdom of God. That is how we find the risen Christ in the poor, the oppressed: not in their goodness but in their need; in their hunger and thirst.

And so the women, the dependent, the victims, seek for what is not there; and it is only because they seek, it is only in their seeking, that the risen Christ appears to them. It is only if we have seen the injustice of our world, shared in the horror of a godless world; it is only if we can feel with and understand people who want to say: "How can there be a God, if I am treated in this way? Where is the power of God, who is supposed to be good and loving? Where is he to rescue me from the concentration camp, the military barracks, the death squads?"; it is only if we understand all this that we are ready to recognise his presence. It is only when we have said "My God, why have you forsaken me?" that we are ready for resurrection.

So, as Frei Betto said, it is only if we first see that we must divide the world into the oppressors and the oppressed that we have any right to talk about believers and atheists. And by that time the words "believer" and "unbeliever" have been shaken almost beyond recognition. Perhaps it is not a matter of who says "Lord, Lord" but of who wants to do the will of our Father.

Then to speak of God is not just to explain the world but to change it. To do what we call theology is to seek the word of God by seeking the word of God made flesh, not by looking in the right place but by tearing away the illusions and lies that conceal the risen Christ, that conceal the victimisation of Christ’s people. Then we shall find him in the victims-but we have not found the victims as victims unless we are with them in their suffering and in their struggle.

I said that Frei Betto’s reply was a piece of wit, because wit challenges the hearer, challenges him to see things differently and to see his own question and his own self, his own life, differently. So I was not too surprised to find (from the Oxford Dictionary) that "wit" and "witness" belong to each other. Witness, like wit, is not giving information, it is a call to conversion and this, as Archbishop Romero reminded us, "is difficult and painful because the changes required are not only in ways of thinking but in ways of living."

So when we say the creed we are not giving the world the benefit of our superior wisdom; we are not telling them a thing or two. The creed is an act of gratitude, in Greek a "eucharistic" act, gratitude for our conversion. For we have collaborated with injustice with Frei Betto’s interrogator and torturer, and still by our apathy and weakness collude with him.

But the Holy Spirit, the forgiving love of God, has allowed us to stand alongside the deprived, the wretched, the victims of our world, so that through them and with them and in them we may recognise our risen Lord and taste of his and their and our victory.

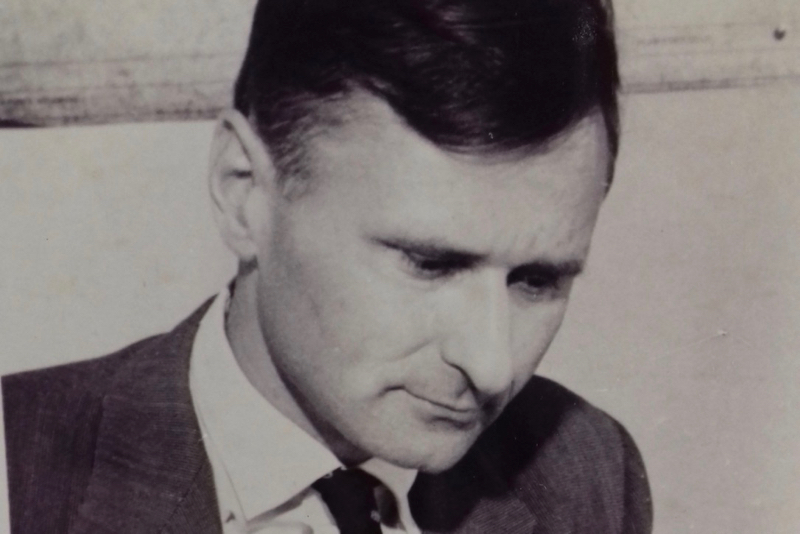

Herbert McCabe O.P (1926-2001) was a Dominican priest, theologian and philosopher. He was the editor of New Blackfriars between 1965 and 1967, and again between 1970 and 1977. Four books of McCabe's writings and sermons were published in his lifetime, and several more were published following his death in 2001.

This essay has been republished from New Blackfriars, the journal of the English Province of Dominicans, with the kind permission of the editor.

In this week's Tablet, our editorial asks what Saint Oscar Romero can teach us today, and Mark Dowd assesses the Archbishop's legacy in a visit to El Salvador, 40 years on from his martyrdom.

Loading ...

Loading ...

What do you think?

You can post as a subscriber user ...

User comments (0)