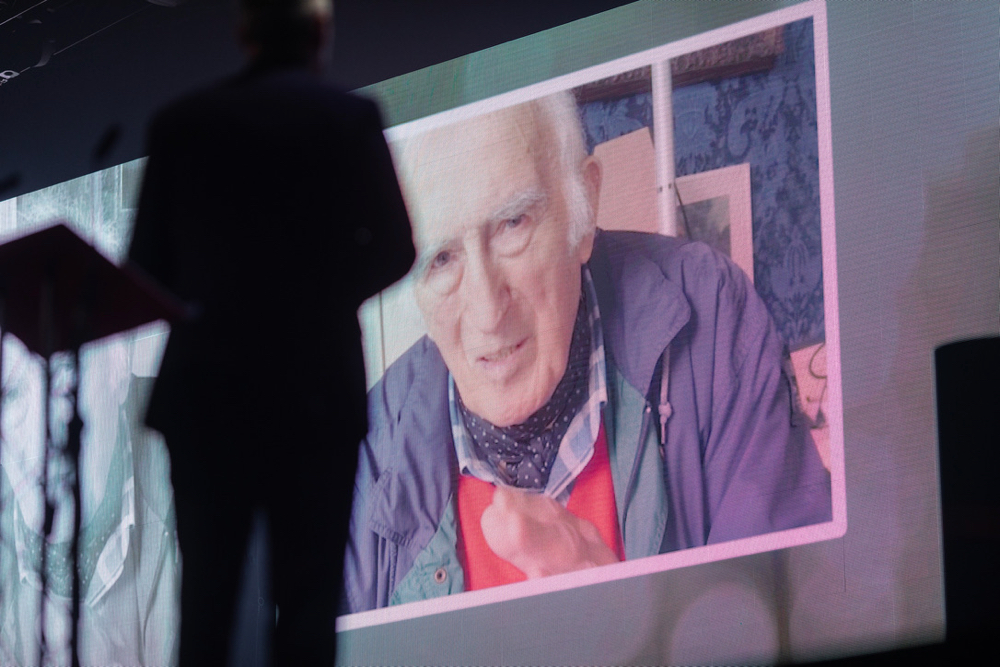

John Habgood, Archbishop of York from 1983 to 1995, and Bishop of Durham from 1973 to 1983, died on 6 March, aged 91. He was one of the most remarkable churchmen of his age. A brilliant scientific thinker, Christian apologist, ecumenist, liturgist and supporter of women's ordination, he was always working on the boundary of theology. He was also prominent in the World Council of Churches, and wrote extensively on a wide range of issues. He made a particular contribution to medical ethics, the dialogue between science and religion, and the place of Christianity in the modern world. Within the Church of England, he was deeply involved in the ecumenical movement, and served on many professional and House of Lords working parties into scientific and technological questions.

He was especially good as a communicator in the press, and often was able to write a short article or letter explaining in simple terms the complexities of a controversial subject while also giving a Christian reflection to justify his own position. On television he was more reserved, fearing that the need for a quick answer would fail to do justice to the question. In the House of Lords or in the Church of England General Synod he came into his own, where his contribution (usually made towards the end of a debate) would summarise the discussion so far and indicate what the central issues were which underlay the argument.

This had a decisive effect on every debate and it was through his leadership in General Synod over twenty years that the Church of England was able to sustain a position he once described as being that of a “conservative liberal”. What was remarkable was that he was not only intellectually brilliant but also prepared to attend innumerable meetings required to build trust and win confidence. He could also speak and write at many levels, from the highly erudite to the discussion of ecumenism at a small group of rural laity and clergy. He was a shy person but he was prepared to meet people where they were. This could be literally true: I remember him arriving unannounced on a wet, windy evening in autumn 1977 when I had just moved into a small mining village in County Durham as the parish priest. He had worked out that his car was a few miles from my house (map reading was one of his great skills) and he suddenly knocked on the front door to welcome me to the diocese.

His reputation was established early on. His first career was as a scientist in Cambridge where his doctoral thesis was on hyperalgesia. He was seen as a highly promising neurophysiologist who lectured and researched as part of a group investigating the nature of pain. Habgood had left Eton as an atheist but at the age of 19 he was converted by an Evangelical mission to the university. It was in a very short time that Habgood broke with his new-found Evangelical friends because of their anti-intellectualism but he did not reject Christianity. Instead his discovery of the dialogue between science and theology fascinated him and gradually drew him into a decision to be ordained in the Church of England. At Cuddesdon Theological College, where he arrived in 1953 at the age of 26, he wrote articles for The Spectator but his impression of Anglican theology was bleak. He found Cuddesdon churchy and disagreed with several of the more conservative lecturers. Life as a curate in Kensington was better, but it was not until he returned to Cambridge in 1956, where he succeeded Robert Runcie as Vice Principal of Westcott House, that he began to find his true metier. The six years Habgood spent at Cambridge were ones of intense theological ferment both within the Church of England and in English theology more generally. Much of that excitement was generated in Cambridge itself, with biblical theologians such as Hugh Montefiore and John Robinson debating alongside patristic scholars like Geoffrey Lampe. Habgood certainly took a leading role in this conversation but his contribution was measured and restrained. He contributed to the highly influential collection of essays called Soundings edited by Alec Vidler in 1962. Nevertheless, Habgood was no clear-cut modernist and found Robinson’s writings rhetorical and imprecise, despite the widespread fame which attended the publication of Robinson’s best-selling book, Honest to God.

Habgood never saw his life as simply that of being a theological academic. He was delighted when Ken Carey who was the Principal of Westcott House, and then became Bishop of Edinburgh, invited him to be Rector of Jedburgh. It was his ministry in Jedburgh which led him to be asked to apply for the post of Principal of Queen’s College, Birmingham in 1967. Habgood rapidly turned it into the first ecumenical theological college in the Church of England, uniting it with Handsworth (Methodist) Theological College.

I have a vivid memory of him leading a group of ordinands from Queen’s and Westcott in 1973 on a visit to the city of Portsmouth. He brought alive the week by challenging the city planners openly on their vision for the city which they were so energetically rebuilding since the devastation of the war had been allowed to remain for too long. His concern was that the continual erection of tower blocks and concrete office buildings was creating a city without a heart. What, he asked, was their vision, and where was the place of the church in all of this? It was a shame he was not listened to, but the planners were unable to answer him at all. However, it was no surprise that in the same year Habgood was appointed Bishop of Durham (the fourth most senior see in the Church of England) at the very young age of 46.

For the next twenty years he was at the centre of English church life. His contribution fell into five areas. First, there was his long commitment to ecumenism. He joined the Churches’ Council for Covenanting in 1979 until 1982, when he resigned commenting on “the bleakness of the immediate ecumenical outlook”. In spite of this setback he remained a member of the British Council of Churches (B.C.C), and took part in the joint Catholic Bishops’ Conference / B.C.C visit to Rome in 1983. He also gave much attention to the World Council of Churches.

Secondly there was his work in liturgical revision where he oversaw the introduction of the Alternative Service Book 1980. Habgood was a cautious reformer, convinced of the need to change but aware from his study of David Martin’s writings that the symbolic function of liturgy could easily be misunderstood. He said in a 1989 presidential address: ‘liturgy ensures that our worship has enough solidity, depth and historical rootedness in Christian tradition, to carry this weight as interpreter of the Gospel.’

Thirdly there was his long advocacy of the ordination of women to the priesthood. Here too, however, Habgood was concerned not to divide the Church of England into schism. As a result, he was the person, above all else, who made it possible for clergy opposed to this change to be given ‘alternative Episcopal oversight’. This was perhaps the most controversial of his decisions but he defended it on the grounds that it gave the Church of England time to come to terms with such a momentous event.

Fourth he was the pre-eminent Christian leader worldwide who understood the nature of the global technological revolution including nuclear power, medical advances and biotechnology. He was tireless in writing, attending conferences, and serving on Government working parties, ever seeking to comprehend and shape the application of technology. This made him a very rare specialist, the highly trained scientist and the religious leader. His House of Lords speech in 1989 on the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Bill was requoted for many years there in future debates on the subject.

Finally, he was a Christian apologist. He defended the establishment of the Church of England as a service to the nation, and his many books included Church and Nation in a Secular Age, Faith and Uncertainty, and Varieties of Unbelief. He defied his critics over the consecration of David Jenkins as his successor as Bishop of Durham in 1984 while making clear that Bishops had a corporate responsibility as a member of the episcopate. Along with his close friend Peter Baelz, whom he persuaded to leave an Oxford theology chair to be Dean of Durham, Habgood was always concerned to explore the subtleties of faith in the contemporary world. In a sermon in Durham Cathedral to celebrate the 1300th anniversary of the death of St. Cuthbert he spoke of how in our day consciousness was divided ‘between the objective scientific understanding of nature, and the passionate intensity of belonging within a world shot through with the glory of God.’ Habgood lived with that tension all his life. He was a person of extraordinary spiritual insight and depth who nevertheless expressed himself with restraint and caution. He could be the most sympathetic listener, with great warmth and a dry sense of humour but he was also aware of the need to preserve ecclesiastical dignity. It was a unique expression of Christian leadership which will be remembered for generations to come.

He was perhaps the greatest Archbishop of Canterbury we never had in the twentieth century. There was a strong campaign in the Daily Telegraph called ‘ABH: Anyone But Habgood’, when Robert Runcie retired in 1991. It was led by Conservative M.P.s such as the Anglican evangelical Michael Alison (father of the Catholic theologian James Alison) and John Selwyn Gummer. Margaret Thatcher instead chose George Carey Despite being better qualified in every respect Habgood was astonishingly loyal and never did anything either in office or in retirement to make life difficult for the Archbishop of Canterbury. The final presidential address to General Synod in July 1995 by John Habgood was an eloquent and moving farewell. It gave an indication of how different things might have been if the Church of England had faced its many divisions in the 1990s under Habgood’s leadership. He warned of the danger of a church turning inwards and becoming obsessed by organisational reform.

He had a long and happy retirement in the small country town of Malton in Yorkshire. His hobbies were painting, carpentry and repairing things. He refitted their camper van, and enjoyed many holidays in it. He was also the Bampton Lecturer on Varieties of Unbelief at Oxford in 1999, and Gifford Lecturer on The Concept of Nature at Aberdeen in 2000. He spoke in the House of Lords well into his 80s on medical ethics. At his funeral in Malton, the parish priest gave a moving tribute to his quiet involvement with the parish church, and his devoted care for his wife Rosalie, who died in 2016.

In an age where religious leaders often respond to changes in technology with disquiet, and prefer the unchallenged simplicity of piety, Habgood remained on the frontiers, ever questioning, accompanying and praying for the modern world in which he was so much at home. As he said in his farewell sermon as Archbishop of York: ‘An archbishop is called to do much of his work on this frontier. As part of the public faith of the Church he has unique access to the places where public policy is made. As one who holds a universal faith, he constantly has to struggle for its public validation. It can be bruising work. We frequently get it wrong. But we rely on the support, prayers and friendship of our brothers and sisters in Christ.’ Such a dialogue remains his lasting legacy.

Loading ...

Loading ...

What do you think?

You can post as a subscriber user ...

User comments (0)