At the Ground Zero sites of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, where atomic bombings instantly killed tens of thousands and destroyed the lives of countless others, Pope Francis shifted the papacy’s position on nuclear.

Before his trip to Japan, it was expected that the Pope would deliver an uncompromising anti-nuclear message and condemn the use of nuclear weapons. His predecessors had done the same.

The Holy See has for years pressed for nuclear disarmament, although past popes tolerated countries holding weapons as a deterrent so long as they were on a path to giving up arms. In 2009, however, Benedict XVI edged the Church closer to an abolition position by saying the “presence alone” of atomic weapons threatens the future of the planet.

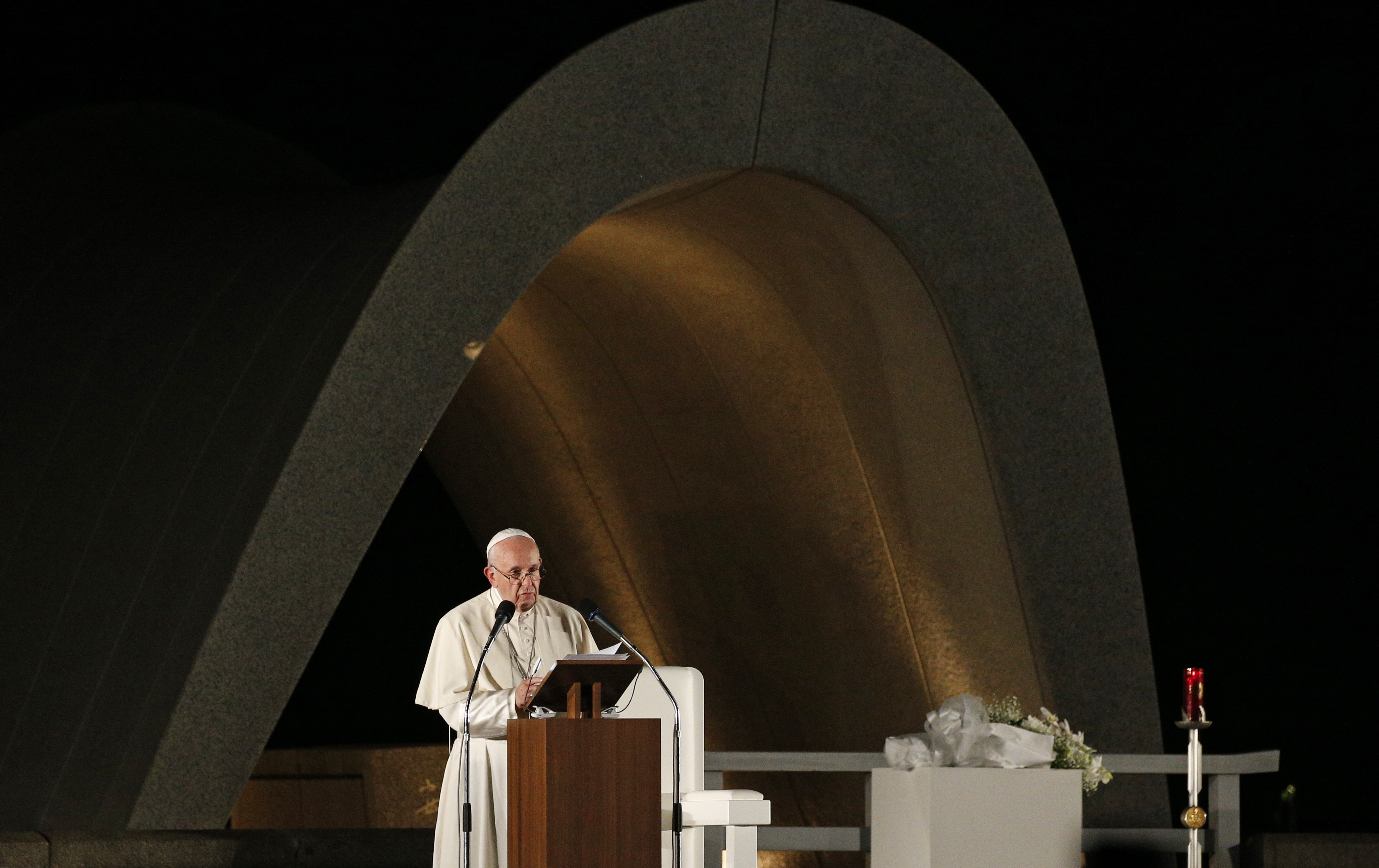

On 24 November 2019, after lighting a candle and praying at a memorial in Hiroshima in the presence of elderly survivors the horrific World War Two bomb, Francis took the Church a step further.

“The use of atomic energy for purposes of war is immoral, as is the possession of nuclear weapons,” said the 82-year-old Pope, adding in the line about possession which was not included in the prepared text. “We will be judged on this.”

Before speaking, the Pope, and a gathering of religious leaders heard from Yoshiko Kajimoto, a woman in her later 80s who was 14 when the bomb was dropped on the United Sates on Hiroshima on 6 August 1945. The death toll in the Japanese city was 140,000 by the end of the year.

“No one in this world can imagine such a scene of hell,” she explained. “I could not tell the difference between men and women, their hair standing on end, their faces swollen to double size, their lips hanging loose, with both hands held out with burnt skin hanging from them.”

The effects of the radiation from the bomb later killed both her parents, while she explained that “most of my friends have died of cancer”. Yoshiko suffers from leukaemia, and had two-thirds of her stomach removed in 1999.

“If we really want to build a more just and secure society, we must let the weapons fall from our hands,” Francis told the gathering. “How can we propose peace if we constantly invoke the threat of nuclear war as a legitimate recourse for the resolution of conflicts?”

Earlier in the day, while in Nagasaki, the other of Japan’s atomic bomb sites, he emphasised that possessing nuclear weapons will not bring peace. After placing a wreath at a memorial to the 74,000 who died instantly after the US dropped a nuclear bomb Nagasaki on 9 August 1945, Francis said he was convinced that “a world without nuclear weapons is possible and necessary”. He also reminded political leaders “that these weapons cannot protect us from current threats to national and international security”.

During Francis' pontificate, the Holy See has become more assertive in trying to eliminate nuclear weapons. Although it has observer status at the United Nations in 2017, it was granted full member status to vote in favour of a draft treaty calling for nuclear disarmament. The Vatican is also urging states to sign up to a 1996 treaty banning nuclear testing.

The Pope revealed the Church’s frustration about the lack of international co-operation on the matter and the general breakdown in countries coming together to pursue common goals. This might also have been a motivating factor in Francis speaking out so clearly on disarmament.

“There is a need to break down the climate of distrust that risks leading to a dismantling of the international arms control framework,” the Pope said in Nagasaki.

“We are witnessing an erosion of multilateralism, which is all the more serious in light of the growth of new forms of military technology. Such an approach seems highly incongruous in today’s context of interconnectedness; it represents a situation that urgently calls for the attention and commitment of all leaders.”

The Pope wrote in a book of remembrance at Hiroshima that he was visiting the site as a “pilgrim of peace” and to “grieve in solidarity with all who suffered injury and death on that terrible day in the history of this land".

What impact will the Pope’s anti-nuclear appeal have? Francis can hope for little more than to stir the consciences of world leaders. He wishes to be a “voice for the voiceless”, to witness to the tensions of the contemporary age where armed conflict is constantly breaking out. He wants a Church that is a leaven of peace, even if the flock is small in number and success by worldly standards is lacking. The Catholic Community in Japan is small, numbering around 500,000 native Catholics in a population of more than 125 million.

“We are to be a little opening through which the spirit continues to breathe hope,” he told them in Nagasaki.

Francis’ visit to Japan, the first by a Pope in 38 years, fulfils an ambition he has had since being a young Jesuit: to arrive in Japan as a missionary. He realised the dream as autumn of his life, as the octogenarian Bishop of Rome and leader of the Catholic Church. This visit was always going to produce something new.

He’s channeled the spirit of two important saints called Francis: St Francis Xavier, the Jesuit missionary who brought Christianity to Japan in 1549, and St Francis of Assisi, the saint of poverty and peace, and the Pope’s namesake. His Japan trip has opened the Church onto the path of a radical, anti-nuclear position.

At the end of his speech in Nagasaki, he called on everyone, Catholic or not, to make the prayer of St Francis their own: “Lord, make me an instrument of your peace.”

Loading ...

Loading ...