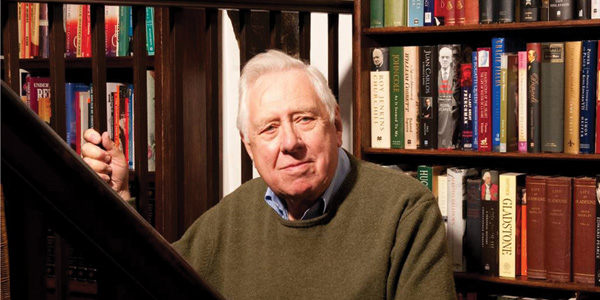

Roy Hattersley’s life has, in one sense, come full circle. He was born in Sheffield 84 years ago in the shadow of the Catholic Church, 11 months after his father, a priest in Nottingham diocese, had left the ministry to marry his mother (though their son only learned the full story four decades later). Now the former deputy leader of the Labour Party lives in a central London mansion block that stands in the shadow of Westminster Cathedral.

His choice of location is a fluke, he is quick to reassure me as he greets me at the door: “I am an unredeemed and unredeemable atheist. I just can’t believe in the magic and the mysteries and the miracles.”

But by the time we sit down in the book-lined dining room and persuade Jake, his English bull terrier, to leave us in peace, Lord Hattersley has softened his stance on the Church. “The whole thing is attractive,” he concedes. “Like Charles I, I find the ceremonies and the liturgy really attractive, especially in a Pugin church – he is one of my heroes. But for me it remains unbelievable.”

Not that such a conclusion has prevented Hattersley from spending the past four years researching his new book, The Catholics, a history of the faith in these islands from the Reformation, through the persecutions suffered by recusant Catholics, up to its almost seamless reintegration into national life today.

For a long time he ran a writing career in parallel with politics, combining newspaper columns and the occasional book with working with Labour leader Neil Kinnock between 1983 to 1992, in often dark days, to make their party electable again. Since he stood down as an MP in 1997 – on the eve of that long-hoped-for victory – his focus has been on books.

Politics, though, remains in his blood. “The Labour Party today,” he remarks in a voice of quiet despair, “is in a neo-terminal condition. I’m not sure it is terminal, but it could become that. It’s not just Jeremy Corbyn, though he is an incompetent and unsuitable leader. Labour is in desperate trouble and I see no one about to fight their way out of it.”

But he isn’t keen to dwell on the subject. “I want this to be about my book,” he chides me gently. So, to business. What made him chose native Catholicism – English, Scottish, Welsh and Irish – as his subject?

“Because religion interests me,” he answers simply. He may reject it for himself, but he is fascinated by others who don’t, and go on to do extraordinary things. His previous subjects for biographies have included John Wesley and the Salvation Army founders, William and Catherine Booth.

The post-Reformation centuries of Catholic penal taxes, priests’ holes and persecution hold a particular appeal for him, because they make for a “ripping good yarn”. The various plots to overthrow Elizabeth I and her successor James I, the martyrs who died for their faith, the switching back and forth between Catholic and Protestant monarchs right up to the Battle of the Boyne in 1690, the uprisings and rebellions, the romantic figures of Mary, Queen of Scots and Bonnie Prince Charlie: they all add up, he enthuses, to “a series of adventure stories”.

The pull of the subject, though, goes beyond the human drama. “What I most admire about the Catholic Church – and I hope my book makes clear there is a great deal I admire about the Catholic Church – is its certainty. A profound rationalist like me ought to have the Catholic Church at the far end of his spectrum, but it is nearer to my beliefs than other churches and that is because of its certainty, which is its true strength and why it has survived.”

For how much longer, though, he isn’t sure. “The Church’s certainty is faced with the pressures to liberalise, especially on family matters. In my terms, as an outsider, quite right too; but I can also see that it is a problem for a Church that for so long has been strong and positive, precisely because it was so definite.”

We are, however, racing ahead to the end of the story he tells over 650 pages. The early sections of his book – Henry’s break with Rome, the different religious directions chosen by his daughters, Mary and Elizabeth, the Gunpowder Plot – are familiar enough, if elegantly retold. It is, though, the aspects of the recusant story he has unearthed that capture his imagination. “I was fascinated,” he offers as an example, “by the efforts of the Catholic gentry in England in the eighteenth century to take over the Church, and the intrigue that caused. I suppose it attracted my class-conscious instincts.”

Equally irresistible are the “what if” questions the story throws up. What if, for instance, James II, the last Catholic monarch, had acted more cautiously after his accession in 1685, or had circumstances treated him differently: might Britain have switched back to being a Catholic country?

“I don’t think it could,” he replies firmly. “We are not by nature a Catholic people. It is all to do with being an island race. I argue at the very start of the book that the Reformation didn’t begin because of Henry’s marital problems, but because England, as an island race, wanted to take its own decisions. And that same desire remained, so James II would never have succeeded [in restoring Catholicism].”

There seems to be an echo of Brexit here. “Yes,” he confirms, “there is very much a parallel – the idea that we are different, that our instincts are to be our own boss, whether it means rejecting the Holy Roman Emperor, the Pope, Brussels or anyone else.”

It is an instinct that left those Catholics who refused to break their allegiance to Rome viewed with suspicion that could boil over into hostility, as in the Gordon Riots of 1780. And that very English view that Catholics are somehow “different” is something that Hattersley feels may not entirely have gone away. He remembers from his childhood in the 1930s and 1940s the attitude that Catholics should be treated with caution, that they weren’t entirely to be trusted.

“Although as I am saying that,” he continues, “it makes me wonder about my father. Did he keep his past as a priest secret because he didn’t want to be seen as different?” He pauses to reflect and then shakes his head. “I don’t think so. The only problem with my father was that he wasn’t married to my mother and we lived in an emergent working-class area, where people wanted to become middle class, and so my parents would certainly have been ostracised had it been known that they were living together.”

Father Frederick Hattersley had been ordained in 1927, but five years later, when preparing a local couple for marriage, he fell in love with the bride. Two weeks after the wedding, they ran away together, though they only married two decades later after her first husband died. It took until his father’s death in 1972 for Roy, just short of his fortieth birthday, to stumble on the truth when he read a letter of condolence sent to his mother by a priest friend of his father’s.

Why hadn’t they ever told him? “They thought I’d despise them, but instead it is the great regret of my life that I wasn’t there to see my father – this diffident, self-effacing, reticent man that I grew up with – in his moment of great heroism.”

From other letters that he has subsequently seen, Hattersley suspects that his father hadn’t ever had a vocation but was pushed into the seminary by family pressure, the chance of continuing his education, and the enthusiasm of the local bishop. His two brothers were also training to be priests. “My mother was the catalyst. She gave my father the courage to give it up. Otherwise, he would have soldiered on, unhappy and uncertain as a priest, but never really committed to it.”

What, I wonder, would the former Father Hattersley make of his son writing a book on Catholics, and dedicating it to him? “Well,” he replies, “his ambition for me was to be a history teacher in a grammar school.” He does not complete the thought, but he is smiling.

The Catholics by Roy Hattersley was published this week by Chatto & Windus. Peter Stanford’s latest book, Martin Luther: Dissident Catholic, is published by Hodder & Stoughton on 16 March.

02 March 2017, The Tablet

Outside in: English have always viewed Catholics as 'different', Labour Party stalwart Roy Hattersley tells The Tablet

The Tablet Interview

Edmund for England

Loading ...

Loading ...

Get Instant Access

Subscribe to The Tablet for just £7.99

Subscribe today to take advantage of our introductory offers and enjoy 30 days' access for just £7.99

What do you think?

You can post as a subscriber user...

User Comments (0)