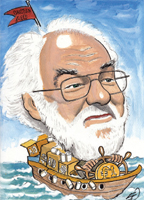

The former Archbishop of Canterbury is now the chairman of Christian Aid. Rowan Williams talks to Madeleine Bunting about his role at the helm of the charity, how inequality of power must be fought – and why the press are good for the soul

Y ou’ve lived in palaces, been entertained by the Queen, had Cabinet ministers clear their diaries to meet you and always had recourse to a readily available slot on the BBC?Today programme to air any thoughts to the nation. Alongside all that prestige and soft power, you have also been subjected to some of the harshest media treatment of any public figure. Lambasted from every side, criticised by friend and foe. By any measure, Rowan Williams’ tenure as Archbishop of Canterbury was a form of media trial. Selected for his huge intellect and holy humility, he struggled to bring them to bear on his attempt to explain faith to an increasingly secular national audience, and all the while his efforts seemed to be thwarted by fellow believers seemingly obsessed with sex. After all that, what do you choose to do next? Was he tempted by a remote post in west Wales, where he could write his poetry and pray like his admired fellow countryman R.S. Thomas? I asked him last week in the House of Lords. He chuckles: “Not yet.”

He was about to give the first Christian Aid parliamentary lecture at a dinner last Friday night in the Lords, doing so in his role as chairman of the aid agency he took on a year ago. We are perched at a table while waiters and waitresses clatter crockery and glasses as they prepare for the evening. But Williams is as calm and present as if in a cloister. You could call this his secret weapon – a quality of attentiveness and presence that wins him many admirers and friends. It is what makes him suited for the role of heading up a major aid agency because he can win friends everywhere. So much of aid agency leadership is a form of diplomacy, building delicate coalitions both nationally and internationally to talk to governments.

But there is another side to heading up an aid agency, and that is public advocacy – making the case for aid; explaining what it does, how it does it and why it does it. Aid is a deeply political subject. It has long since drifted away from apolitical charity, and Christian Aid’s position is unequivocally clear: its struggle to end poverty is profoundly influenced by its analysis of power. Last week’s lecture, in which he talked about the redistribution of power as crucial to tackling violence and poverty – just as vital in tackling inequality as the redistribution of wealth – was one of Williams’ first stabs at laying out how he proposes to take on this territory.

“The truth is that poverty and a sense of powerlessness are regularly among the major drivers of violence,” he told his audience, “while violence in turn is a major driver of poverty. So what we must do is recognise the vicious circle here, and ask where and how we break it.”

While there were some striking sound bites – “Christian NGOs need to move just beyond ambulance work” – the lecture also exposed some of the quirks that got the man now ennobled as Lord Williams of Oystermouth into so much trouble back in his days as Archbishop of Canterbury.

On occasion, he is prepared to take on politically sensitive subjects, but then fudges it. For example, in last week’s lecture, he raised the subject of the securitisation of aid – the practice of shifting aid money into programmes closely associated with military operations. Williams says: “Whether or not this is fair (and it should not obscure the rather substantial achievement by successive governments of avoiding direct cuts in aid expenditure), it’s tempting to suggest that we expand our aid budget by redefining aid projects as security related.”

Then, talking about the inequality of power across the world, he pleads with governments and financial institutions to “show more courage” and to share power. But the powerful rarely give up power by choice.

There is no question that Williams is game – he recently took up the Christian Aid challenge of living on £1 a day for five days. He talks with real warmth and feeling about his experiences in Africa. He spent some time in South Africa in the 1980s and describes it as life-changing.

“There was something raw and essential about the Church there; you see a little bit into the heart of things,” he recalls. “I felt the same in Zimbabwe. The extraordinary experience of being with Christians who have been savagely persecuted by the security forces, and yet there was a swelling of joy and hopefulness. The congregations who were barred from their churches met under trees. It was the closest experience to the Early Church. You come back and say that’s what it’s all about. Defying Mugabe because the Gospel matters more. In Africa, lots of people find that a layer of protection is taken away and one is a bit more in touch with human and other realities.”

There are interesting challenges ahead in helping to steer Christian Aid. The charity, which was central to the success of Jubilee 2000 and Make Poverty History in 2005, is almost a victim of its own success. In the last financial year, it received £38 million in grants from the UK Government and the European Commission, nearly half its annual income. So while its annual report and website is all about the 100,000 volunteers who will go door to door during Christian Aid week, the reality is that their contribution of just under £13m is dwarfed by government contracts.

Williams’ tricky job as chairman will be to tell a coherent, overarching and credible story. One wonders whether the campaigner he used to be – he was arrested at the US air base at Lakenheath in 1985 on a CND protest – might re-emerge. And if not, why not? Have the intervening decades spent running cumbersome institutions worn down his radicalism, replacing it with a pastoral preoccupation to keep everyone talking to each other?

The other major part of Williams’ post- Canterbury life is as master of Magdalene College, Cambridge, and he admits ruefully that he spent much of the previous day interviewing architects. “I like being in an academic community. I was attracted by making it work and I enjoy that contact with students. It doesn’t feel too rarefied although it’s very beautiful. It’s very preoccupied with keeping its doors open.”

It was an open secret at Lambeth Palace that his real delight was a few hours with an obscure theology text, so it comes as no surprise that he has headed back into the leafy privilege of Cambridge academia and a round of international lectures and writing books. It is striking that the Welsh radical who once talked openly of disestablishment has ended up running so many establishment institutions of national stature. Yet he is ambivalent about the experience. There is a gleeful “Yes” at the suggestion that leaving Lambeth was a vast relief. At quiet moments, does he think about his time in office? “Of course. I look back and ask questions – did I make a difference? – knowing myself that I will never find adequate answers, but I can’t stop asking.”

Are you glad you took the job? “Well, yes. Not because it was a bundle of fun. But the Church was calling me to do something and I felt I ought to do it. But I don’t want to be mean-spirited. It opened lots of doors and forged friendships. It took me to many places. There’s a strange aspect of the job whereby you go from a school assembly to lunch with the UN secretary general – and that’s based on a real incident.”

Does he feel he was misunderstood? “I don’t want to whinge about modern communications,” he says. “It doesn’t help.” Then, after a pause, he continues: ‘There is something about the sheer rapidity and reach of global communications which is increasing more than ever. Misinformation goes faster than the truth can. I am much happier talking to people I can see. I can think, what do these people need to hear? Broadcasting, I have to think extra hard about who’s listening and then resign yourself to be misunderstood and live with that.”

Did he ever look at the press cuttings when he was at Lambeth? “Against the advice of friends, I did read quite a lot. I’m sure it’s good for the soul. You need to know. It is really poisonous if you’re protected from the critical voices out there. Your most ambitious self- image needs to know that you may still look like a complete idiot.”

Williams is laughing again and it’s time for him to start mingling with the arriving dinner guests. He’s off to do what this shy man does surprisingly well, meeting and greeting, making friends and changing minds.

* Madeleine Bunting is an associate editor at The Guardian.

Loading ...

Loading ...

What do you think?

You can post as a subscriber user...

User Comments (0)