It’s a popular hymn at weddings and an emblem of Englishness, but the story behind William Blake’s words and Hubert Parry’s music is complicated and contested

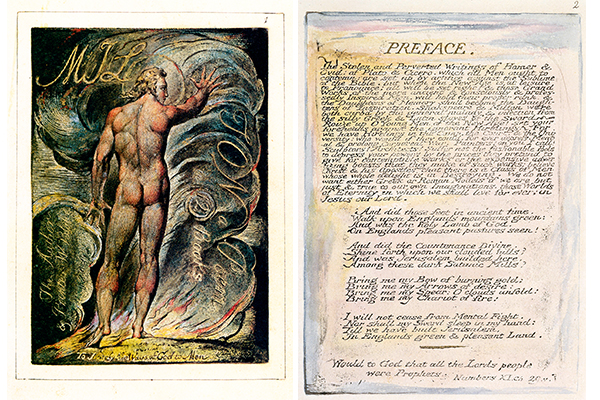

On 10 March 1916, the composer Sir Hubert Parry handed over a manuscript to his friend and former student, Henry Walford Davies, remarking rather casually: “here’s a tune for you, old chap. Do what you like with it.” The tune was Parry’s setting of William Blake’s “And did those feet”, a lyric poem of four stanzas that Blake had included in the Preface to his illuminated “book in two parts”, Milton: A Poem. Parry had been commissioned by the Poet Laureate Robert Bridges to set Blake’s poem – which had been almost forgotten in the 100 years since he had written it – for Fight for Right, an organisation set up by the explorer and adventurer Sir Francis Younghusband to raise morale during the First World War. “Jerusalem”, as it became more famously known, was instantly popular and over the following century would become established as a patriotic hymn of England and Englishness.

The common assumption is that “Jerusalem” became an integral part of the national consciousness following the war. When I told people that I was writing a history of the hymn, many would regale me with memories of singing it at school assemblies or on the cricket field, and assume that I was driven by a similar nostalgia. The truth is, however, that I have no recollection of hearing Blake’s words and Parry’s music before seeing the film Chariots of Fire on television in the early 1980s. Although I had long been an altar boy, I cannot remember the hymn being sung at my Catholic school or in my parish church. Certainly, it was not a staple of The Westminster Hymnal (1952) nor Petti and Laycock’s New Catholic Hymnal (1971), although it was included in compilations such as the London Oratory’s The Catholic Hymn Book (1998) and the Catholic edition of Hymns Old & New (2008). As an athletics-obsessed teenager, I was more interested in a film about running and, if pushed, Vangelis’ opening soundtrack than the traditional performance that ends the film. It was only when I took up a scholarly interest in Blake that I became aware of the significance of the stanzas from the Preface to Milton.

User Comments (1)