An experienced translator of ancient texts reflects on the particular problem of rendering words considered to be divinely inspired into modern English, and explains why modern Bible translation now uses inclusive language as a matter of course

The Bible nearly always comes to us through translation. The consequences of this can be overlooked by those whose lives are affected by Scripture, especially if they are monolingual and have not engaged in trying to understand an unfamiliar foreign language. A translation is the result of a series of decisions about the meaning of words, decisions based on understandings of their grammar and syntax, and of the style and purpose of each phrase, clause, sentence, paragraph, chapter and book. This matters, since the Bible is foundational to more than one religion, and those who entrust themselves to what is told and taught in its pages grant it a unique authority. Although most thinking readers do not take this authority in a literal word-for-word form, but grant it to the whole, a whole which developed and changed over the centuries of its composition, they still see it as communicating essential truths not available elsewhere.

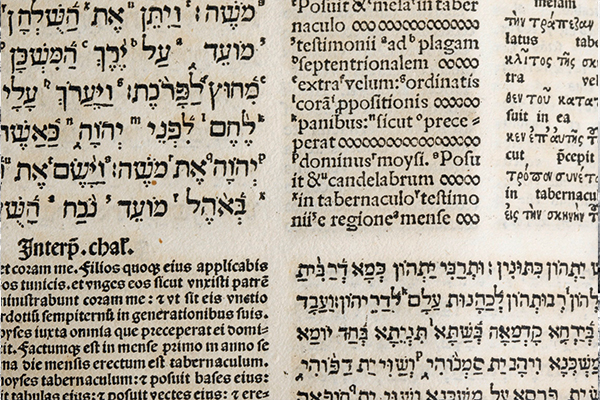

The Old Testament, unlike the foundational documents of some other religions, was not left in its original Semitic languages, but translated in the second century BC into Greek, a language more familiar to many Jews than those of the ancient original texts. The Old Testament was often read in Greek by Jews and, when supplemented by the New Testament, by Gentiles. In the West, the Bible was put into Latin; then into other languages, translated from Latin, or from Greek, or from Greek and Hebrew. Translating the Bible into English did not begin with Wycliffe; there were several Anglo-Saxon translations. Our Bibles today are in our vernacular tongues; Greek and Latin are learned tongues from the past. But for centuries they were popular tongues also. The word “vernacular” comes from verna, a household slave.