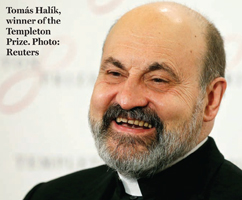

In the first of two interviews this week with clergymen who have made outstanding contributions to the Church and the wider world, Jonathan Luxmoore talks to the winner of this year’s Templeton award, the Czech Fr Tomás Halík, who was active in the clandestine Church of the Communist area

In Prague’s Baroque Most Holy Saviour university church, a smiling, bearded priest greets his youthful congregation. Beyond the glass doors, tourists wander past fashion boutiques bordering the medieval Charles Bridge, against a background of steeples and turrets running uphill to Hradcany Castle.

At 65, Mgr Tomás Halík displays a shyness that belies his importance as a religious philosopher communicating the Christian message to a deeply sceptical society. With his achievements now acknowledged with the prestigious Templeton Prize, the influence of this modest Czech pastor looks set to attain new heights.

“It’s an honour not just for me, but also for my teachers – people who bore the cross in prisons, camps and uranium mines so I could enjoy the Easter of freedom,” Halík told me. “But it’s also a moral obligation to go deeper in my thinking, and develop the culture of dialogue which is so important for today.”

When the “Theological Nobel” was announced last week, it was welcomed by Cardinal Dominik Duka, a former Communist-era fellow dissident, as a reminder that Central Europe was “not just a place where religion and theology were once persecuted”, but also a home “to people of deep thought who can speak to audiences in Europe and other continents”.It places Halík alongside such luminaries as Mother Teresa of Calcutta and Alexander Solzhenitsyn. But it also crowns a remarkable, often dramatic career, which has varied from dodging the secret police in underground seminars to visiting professorships in at least 20 countries.

He was born in Prague on 1 June 1948, four months after the Communist seizure of power; his roots lay not in Catholic tradition but in the secular humanism of Czechoslovakia’s modern founder, Tomas Masaryk. His father, a literary historian, was a close friend of Masaryk’s favoured playwright, Karel Capek, so when Halík became a Catholic at 18, it meant going against a family tradition.

“It was partly protest, partly affectation, partly the search for a new dimension,” he explained to me in a previous interview. “Perhaps I also wanted something which differed absolutely from Communism, and humanism never quite did so.”

He studied sociology and psychology at Charles University, and philosophy with the revered phenomenologist, Jan Patocka, who died in 1977 after a police beating. During the 1968 Prague Spring, he was elected a student leader and helped set up a Movement for Conciliar Renewal, the DKO, to promote the ideas of the Second Vatican Council.

Halík’s conversion had owed much to English Catholic writers such as G.K. Chesterton and Graham Greene, in whom he found “the Catholicism of a minority, without triumphalism”, as well as to John Henry Newman, whose emphasis on conscience suited someone versed in the Czechs’ own “martyr of conscience”, Jan Hus (1369-1415).

He was on a course in religious philosophy at Bangor University (Wales) when, in August 1968, the Prague Spring was crushed by Warsaw Pact tanks. He considered political asylum, but eventually decided, “after praying all night”, to return home.

Halík trained for the priesthood underground while working with drug addicts and alcoholics as a psychotherapist. In October 1978, he was secretly ordained during a visit to Erfurt in neighbouring East Germany. By then, Czechoslovakia’s Charter 77 human- rights movement was helping create a “parallel culture”. It was an atmosphere in which Halík thrived.

As an underground university chaplain, Halík arranged secret seminars for such visiting theologians as Hans Küng and Johann Metz. He also got to know the playwright Václav Havel, a Charter 77 spokesman and later president of the Czech Republic, and gained a close friend in Fr Josef Zverina, a Jesuit priest and Charter signatory who had survived Nazi and Communist incarceration.

After the 1989 Velvet Revolution, Halík became one of many former dissidents thrust into prominence. He was named secretary general of Czechoslovakia’s revived bishops’ conference and a member of the then Pontifical Council for Dialogue with Non-Believers, helping plan the Pope’s April 1990 pilgrimage, his first to post-Communist Eastern Europe.

But the attraction of such positions soon ended. He quit the bishops’ conference in 1993, the year Czechoslovakia split into separate states, and succeeded the late Zverina instead as head of the ecumenical Czech Christian Academy. It turned out to be the right move: Halík’s strength was as a man of ideas, not as a church bureaucrat. Like many Czechs, he had also grown disillusioned with the Church’s post-Communist preoccupation with money and property and frustrated at the Church’s failure, as he saw it, to reach out pastorally to the non-believers he collaborated with under Communism.

In 1998, he led calls for wider democratic representation and founded a protest movement, “Impuls 99”. In a radio broadcast, President Havel let slip he would “willingly see” Halík as his successor when his second term ended in 2003 and others urged him to run for the Senate but he eventually abandoned the idea.

Since then, as professor of sociology at Charles University’s religious studies department, Halík has flourished intellectually, gaining an audience at home and abroad for his cherished “philosophy of dialogue”. It was born, he explains, from his encounters with Catholic priests who had spent time in Communist prisons and labour camps alongside inmates from very difficult philosophical and ideological backgrounds. The Church of the future, they had concluded, must be a serving Church – precisely the vision that seemed to have emerged from Vatican II.

Halík has debated internationally with scientists and atheists, as well as with Jews, Muslims, Hindus and Buddhists, and gained respect among Czechs as an advocate of social reform and an outspoken opponent of racism and intolerance.

But he is most attracted, as a student chaplain, to those he describes as “seekers after God”.

“I say to atheists not that they’re wrong, but that they lack patience,” Halík explained. “The interpretation that God is silent or dead isn’t patient enough. We need the virtues of faith, hope and love to see God through his apparent hiddenness.”

Just how much weight that would be given by today’s militant New Atheists is another matter. But Halík’s message is that faith itself is easily misunderstood. Far from bringing certainty, faith teaches a way of living with the mysteries and paradoxes of life in an ambivalent world. It offers, as the French mathematician-philosopher Blaise Pascal (1623-62) noted, “enough light for those who want to believe and enough shadow for those who do not”.

Does the contemporary Church reflect this? Halík takes up Carl Gustav Jung’s metaphor comparing the life of mankind to a single day. He rejects the view of atheists that Christianity is approaching its end, and the claim of Teilhard de Chardin that Christianity is “at its beginning”. The image emerging instead is of a “Church at noon-time”, challenged to decide whether to consolidate its existing structures and practices, or to venture further and deeper in a continuing spiritual development. Both conservatives and progressives make the mistake of taking the Church’s institutions too seriously, he thinks. If renewal is to happen, the signs of the times must be read with greater imagination and vigour.

For a contemporary society needing critical feedback, the Church must offer a “competent, clear, powerful and prophetic voice”. It must also be a “school of true virtues”, showing how faith, hope and love can still provide guiding lights to a world clouded in complexity and confusion.

“The Church has promised love, respect and fidelity to today’s people, so we can properly ask how well it’s kept this promise,” Halík explained. “After so many conflicts and misunderstandings, there are times when dialogue within the Catholic Church seems more difficult than the Catholic dialogue with other religions.”

Halík says he is delighted the Templeton award was announced on the first anniversary of the new pontificate. He sees Pope Francis as a man after his own heart – close to people and open to dialogue, offering the vision of a simple Church serving the poor and downtrodden.

Whether the new pontiff has a real impact will depend on Catholics themselves, Halík thinks, and on whether he is treated as “just an admired icon”, or as a “true spiritual model”. He points out that as Martin Heidegger (1889-1976) observed, the world of modern technology has created bridges but has not always brought people closer. So the Church’s task is to cultivate a “culture of nearness”, something the new Pope seems intent on doing.

“I’m relieved my own voice isn’t connected with any great formal authority, and that I’m still free to talk and express my views according to my own conscience,” Halík said. “If this honour gives me the chance to extend my work and be more visible internationally, that will be helpful. But it also carries a challenge which I plan to take very seriously.”

Jonathan Luxmoore writes for The Tablet about Eastern and Central Europe.

Loading ...

Loading ...

What do you think?

You can post as a subscriber user...

User Comments (0)