Do you get anxious every Friday the thirteenth? If so, you might want to stop reading now, for according to traditions stretching back to Classical antiquity, every month has two unlucky days. We’ve just survived the one on 30 August and another is about to strike tomorrow, on 3 September.

In the medieval centuries, these 24 days of ill-omen were known, for reasons I’ll explain presently, as the “Egyptian Days”. The best minds of the medieval universities of Paris and Oxford directed their intellectual firepower to discovering the origin of these ill-fated days and to devising prophylactics and palliatives against the evil they were believed to bring.

Woe betide those who did not heed when these days of ill-fortune fell. Catchy verses were therefore composed to fix their annual recurrence in the minds of the medieval faithful, princes, prelates and paupers alike.

Belief in these days of bad tidings was part of the medieval world’s Classical legacy. The ancient Romans were, to put it mildly, a superstitious bunch. Their calendar was peppered with various “dies atri” – “dark” or “black” days when it was considered unwise to embark on any new task, sacrifice to the gods or celebrate a religious rite. Starting in the mid-fourth century, these superstitious, pagan beliefs inveigled themselves into the liturgical calendars of the nascent Church, ultimately morphing into the “dies aegyptiaci” or Egyptian Days of the Christian Middle Ages.

They were so called because the medieval mind associated ancient Egypt with magic and soothsaying. By the eight century, it was accepted that there were 24 Egyptian Days per year with two allocated to each calendar month. Their origin was thought to lie in the plagues which a vengeful God visited on the Egyptians to convince the Pharaoh to release the Israelites from slavery.

Each Egyptian Day was believed to mark the date of a disaster inflicted on the ancient Egyptians.The fact that Exodus describes a mere ten plagues was no obstacle to this becoming accepted fact. Peter Comestor (d. 1178), a leading theologian at the university of Paris, offered a ready explanation: in addition to the ten plagues enumerated in Exodus, there were an addition 14 minor plagues that Moses didn’t think worth recording. In a classic case of circular reasoning, John of Trevisa (d. 1402), an English author and translator active in the late fourteenth century, argued that the total number of Biblical plagues could be surmised from the 24 Egyptian Days of his own time.

Just about every human activity was deemed unlucky if undertaken on an Egyptian Day. This included receiving medical treatment and even giving birth – those born on such a day were thought to be destined for a life of misfortune and misery.

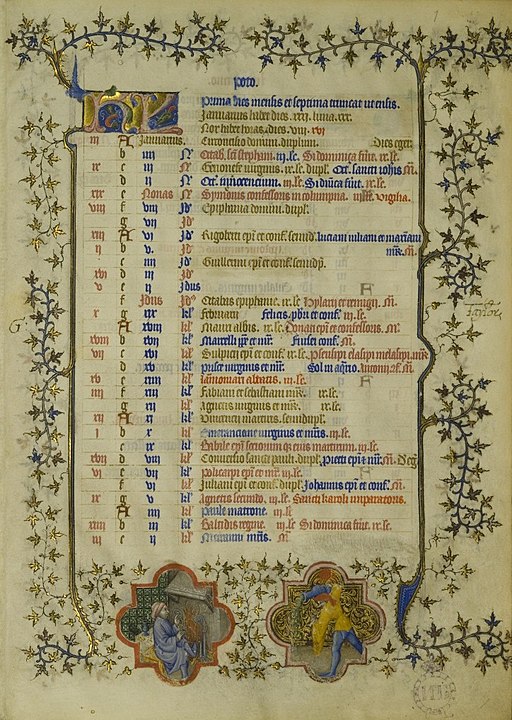

Also called “evil” or “dismal” days, their occurrence was routinely recorded in medieval liturgical calendars. An example from Whitby Abbey dating to c.1400 shows that its monks believed the following days were laden with a heightened risk of misfortune: 1 and 7 January, 3 and 4 February, 1 and 4 March, 10 and 11 April, 3 and 7 May, 10 and 15 June, 10 and 13 July, 1 and 2 August, 3 and 10 September, 3 and 10 October, 3 and 5 November and 7 and 10 December.

In common with other calendars, the Whitby manuscript contains mnemonic verse explaining the specific evils associated with each of the Egyptian Days.

The first day of the month and the seventh cuts like a sword / The fourth leads to death, the third overthrows the strong man / The first disrupts he who orders (or sends), the fourth he who drinks?/ The tenth and eleventh are full of the face of death / The third kills and the seventh strikes the coasts (or the earth)?/ The tenth turns one pale, the fifteenth is ignorant of treaties, alliances / The thirteenth of July immolates, the tenth shakes to ruin / The first kills the strong man, the second overthrows a company / The third of September and the tenth bring evil to limbs / The third and the tenth are as the death of someone / The fifth is Scorpius and the third is girt with slaughter / The seventh deprives the manly of blood, the tenth is as a serpent.

But dates could differ between calendars, and in addition to the days listed above, 25 January, 26 February, 28 March, 20 April, 25 May, 16 June, 22 July, 30 August, 21 September, 22 October, 28 November and 22 December were also regarded as “dismal”. Some authorities even went so far as to identify the exact hour when the risk of ill fortune was at its greatest.

However, medieval people clearly didn’t believe that they were entirely helpless in the face of such misfortune. A mid-fifteenth-century manuscript now at the Bodleian Library, Oxford, lists the “perilous dates for to take eny sekenes in, or to be hurte in, or to be weddyd in, or to take eny Journey vpon”, but crucially adds that God would still provide His protection on these days.

Moreover, even in the Middle Ages, belief that the Egyptian Days were a portent for ill luck was far from universal. William of Newburgh, a twelfth-century Yorkshire Augustinian canon and chronicler, readily accepted that bodies could rise from their graves and torment the living, but dismissed belief in the Egyptian Days as nothing more than a pagan superstition – at least as far as Christians were concerned. William asserted they were still a reality for the the Jews, and in keeping with the virulent anti-Semitism of his age, he cited the Egyptian Days as a reason for the pogrom in York that culminated in the mass suicide, slaughter and forced baptism of the city’s Jewish population at York’s royal castle (Clifford’s Tower) in March 1190.

Canon lawyers also viewed the Egyptian Days with skepticism, so too the astronomer Bona de Luca, who in 1254 argued that their widespread presence in calendars was to commemorate the plagues of Egypt, and that as anniversaries or feast days honouring miracles worked by God, they were not to be feared. I can’t help but think he was a very clever fellow indeed.

Loading ...

Loading ...

What do you think?

You can post as a subscriber user ...

User comments (0)