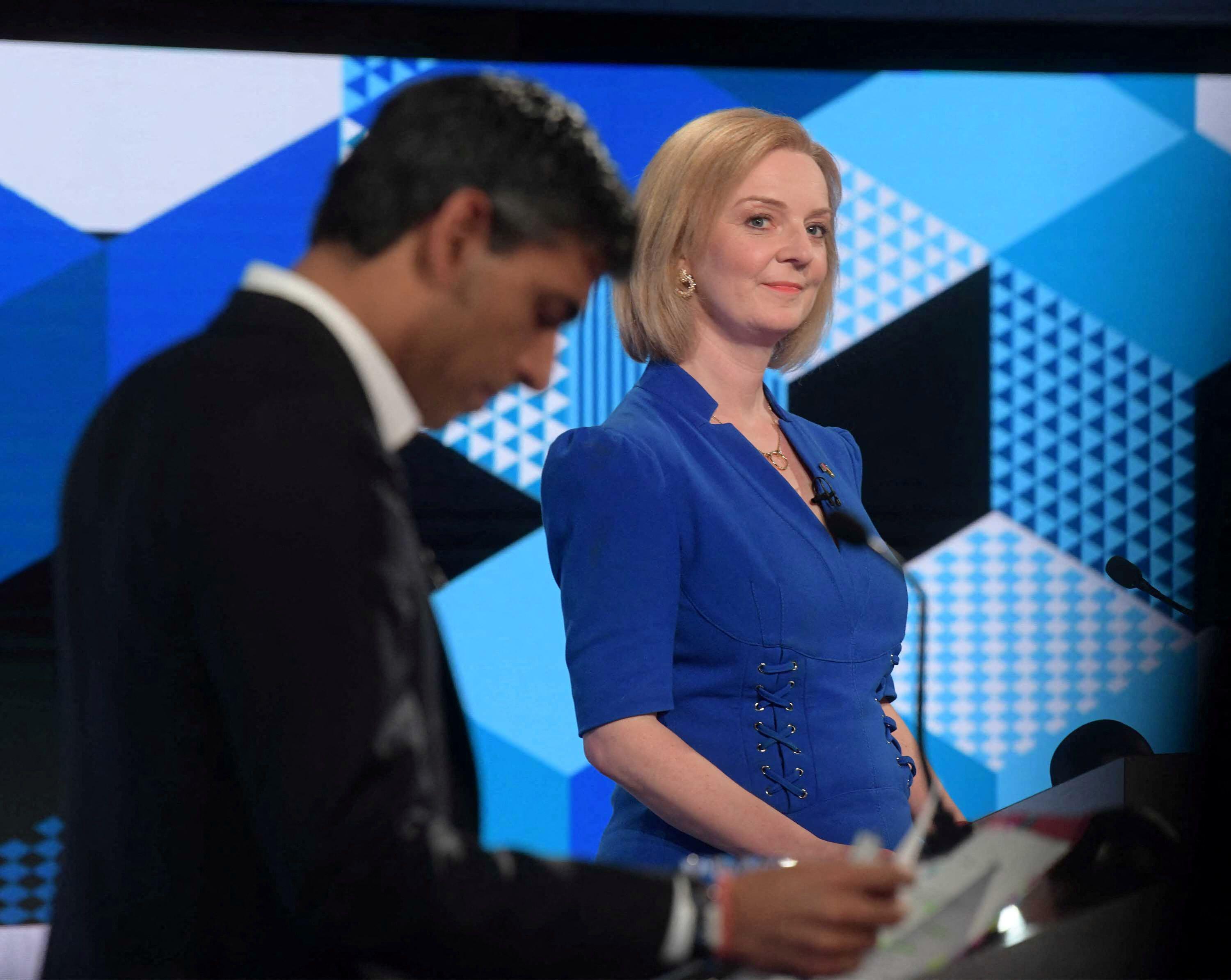

In the past few days, the Tory leadership race entered the educational arena with both candidates Truss and Sunak declaring a view that we need to create more grammar schools, clearly demonstrating that both have a complete lack of understanding as to what the current issues within the education system are.

In the 2019 election, the Conservative party won a landslide victory, hoovering up many traditional Labour heartlands in the north of England with a manifesto centred on “levelling up” and the promise to pour more funding into areas that have so often seen little investment.

However, this new pledge to open new grammar schools is completely at odds with their election winning manifesto and the mandate that was given to the party by the people. A policy such as this would seek to draw an even greater dividing line through our society and place children at the centre of this division; this is not levelling up.

If we take a closer look at the school-level data in areas that contain grammar schools then we get a better understanding of the division that is created with a move to this system.

The national average in England, in 2019 (the last time we had a full set of examined GCSEs), for students leaving school at 16 with a strong pass in both English and mathematics, was 43 per cent. Acquiring at least a grade five or above in English and mathematics is fairly essential in advancing on to A-level programmes of study.

While not every student may want to advance on to A-levels, we have a clear duty to try and ensure as many students as possible have this opportunity at their disposal, as well as a strong grasp of both English and mathematics.

Let’s take the political constituency of Sleaford and North Hykeham in Lincolnshire which has two selective grammar schools and five non-selective secondaries.

Both of the selective grammar schools saw their students attaining significantly above the national average with strong passes in both English and maths – 86 per cent of students at Sleaford and Kesteven Selective Academy attained this threshold.

The picture in the other five secondary schools, educating 6.4k students, is much bleaker, with every single one being below the national average by the same measure, with a mere 22 per cent of students at North Kesteven Academy attaining strong passes in English and mathematics.

It’s not surprising that in the “Levelling Up” White Paper, published in February 2022, some three years after the 2019 election, Lincolnshire has been named as an “education investment area” due to their low standards. This is a pretty damning indictment of the grammar system by the government itself.

There are some other far more crucial areas that the future prime minister must turn their attention to in education rather than vanity tropes such as “introduce more grammar schools”. Today the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) dealt a hammer blow to the government highlighting that it would not meet its pledge to “restore per pupil funding” to 2010 levels by 2024-25; a promise made by none other than, Rishi Sunak himself. In fact the IFS have stated that it is likely that, due to inflation, funding will be 3 per cent less than 2010 levels.

This is not “levelling up” in any shape or form. At the Exeter hustings we heard the candidates talk about a fairer funding formula to support more rural schools, but this was announced by Justine Greening in 2016 and has been consistently kicked down the line.

There is a plethora of local authorities that have run into deficits on their “high needs block”, the funding reserved for some of our most vulnerable children, those with special educational needs, resulting in cuts at both local authority and school level. There simply isn’t enough money within the system to meet the demand. Put simply, financial investment in education is withering on the vine.

On the last day of the summer term, the government announced a 5 per cent pay increase for teachers that will not be funded but would rather have to be found within existing budgets. Unfortunately, half of the schools in England have already set their budgets, in March, therefore an announcement by the Department for Education four months into the fiscal year demonstrates a complete lack of understanding for how school budgets operate.

In a survey conducted of more than 1400 schools by Teacher Tapp, 58 per cent of schools stated that they couldn’t afford these pay rises with a further 28 per cent stating they were still unsure whether they could afford them or not. These are worrying statistics. Schools are currently using the increased investment that was announced last year to attempt to cover the rising energy costs that are coming this winter: for most schools this is around two and a half times more than last financial year (for my school we are estimating £110k on energy costs). Many schools will struggle to break even at the end of this financial year with leaders focusing their energy on what to cut from their budgets rather than focus on offering the very best support.

Maybe the leadership contenders could set their sights on their plan for recovery in education post the Covid-19 pandemic. Since emerging from the pandemic, attendance levels of students in schools has remained significantly low: an astounding four percentage points below the 2019 national average, prompting the Children’s Commissioner, Dame Rachel De Souza, to set this as a key target and focus for all schools.

In fact, government narrative around post-Covid recovery in schools has gone remarkably quiet in recent months and has come nowhere near to touching the £15 billion that was advised by Sir Kevan Collins, the recovery education expert appointed by Boris Johnson to assess the educational need for children post-pandemic.

His words upon resigning from his post were pretty disconcerting. He said: “A half-hearted approach risks failing hundreds of thousands of pupils. The support announced by government so far does not come close to meeting the scale of the challenge.”

Furthermore, this summer we will see the first set of exam results since 2019 and potential issues regarding admissions to university as there are forecasted to be fewer places available, what will happen to these students and their ambitions?

The next Prime Minister, be it Truss or Sunak, has an awful lot to contend with to ensure that we, as a nation, can provide a first-class education to all of our young people after what has been a very difficult few years.

The issues and problems I have listed are not insurmountable and can be tackled if the government places education at the heart of its agenda.

Unfortunately, the reintroduction of grammar schools is simply not the answer and the fact that both candidates have placed this at the centre of their pitches to their party is gravely concerning. We can only hope that they both come to appreciate that their spontaneous “vote-catching” responses in this matter will result in damaging the educational progress of many thousands of young people.

Loading ...

Loading ...

What do you think?

You can post as a subscriber user ...

User comments (0)