When a public officer, acting as such, wilfully neglects to perform his duty and/or wilfully misconducts himself to such a degree as to amount to an abuse of the public’s trust in the office holder, without reasonable excuse or justification, guess what? He can be charged and tried in the Crown Court with the common law offence of misconduct in a public office, maximum penalty life imprisonment.

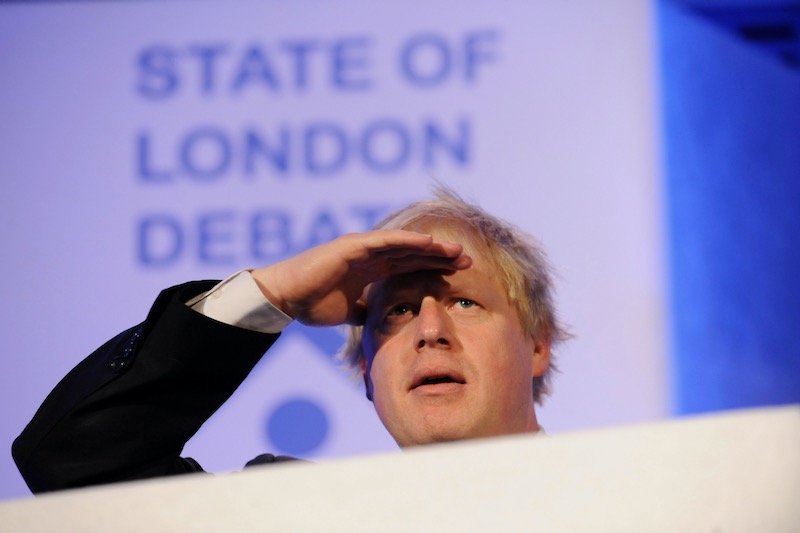

My first sentence is a direct quote from official guidance to prosecutors issued by the Crown Prosecution Service for England and Wales. And the jaw-dropping thought occurs to me, and may have occurred to the Metropolitan Police, that one person who may have committed the offence is the Prime Minister, Boris Johnson.

Suppose the report by Sue Gray, the senior civil servant called in to investigate partygate, finds him culpable for a series of breaches of statutory regulations, which he either caused or condoned. Does that not suggest that every detail of the criteria defining the crime of misconduct in a public office may have been satisfied? Surely it does so at least prima facie, that is to say there is a case to answer.

This would be the constitutional crisis of the century. How on earth would the police handle it? The answer, I suspect, is by the book. Not for nothing is their nickname PC Plod. They would follow the normal steps of any criminal investigation, from A to B to C. If there is evidence of a crime, they would arrest the alleged perpetrator and question him or her under caution, and after receiving legal advice from the CPS along the lines of my first sentence, charge them or release them. If the former, they would be brought before a magistrates’ court, remanded to the Crown Court for trial, and either released on bail or taken into custody.

The law says the charge of misconduct in a public office should only be brought where there was no statutory offence available that covered the same facts. Dereliction of duty could then be offered to the sentencing court as an aggravating factor, increasing the severity of the likely sentence for the statutory offence. But causing or authorising a systematic breach of Covid regulations would not by itself be a separate criminal offence against statute law. So that would leave the way clear for a charge under common law.

Given that a breach of Covid regulations is normally covered by a fixed penalty notice, and only goes to magistrates for summary trial if the allegation is contested, there is no reason to suppose that release of Sue Gray’s report would prejudice these low-level processes. Magistrates are supposed to be immune to public or media pressure – and I hereby declare an interest as I am one myself, albeit now on the supplementary list.

One is forced to conclude, therefore, that the Met has bigger fish in mind. There is at least the possibility that a serious crime has been committed. Let us suppose that two or more witnesses have told Sue Gray that the Prime Minister, when asked, had said that there was no need to worry about the rules “because, after all, they’re hardly going to come in here and arrest us”. And maybe added: “We could always say it was a work event.” (I have no idea whether that actually happened). That would certainly amount to an abuse of the public trust as it would encourage people to break the rules themselves.

A prime minister as such has no protection against prosecution, and if things ever got this far, the clamour for his or her immediate resignation would be irresistible. Yet there is one conceivable loophole in this scenario. The attorney general, a government minister, has the power to take over a prosecution on public interest grounds and then abandon it. But they would have to withstand a judicial review, and try to justify such actions in court. I do not imagine for one minute the courts would wear it. And think of the deluge of bad publicity, the outrage on the streets, in the media and in Parliament.

This sketch of one possible outcome of the partygate impasse in British politics may seem improbable. But improbable does not mean it must be wrong. Sherlock Holmes tells us in The Sign of the Four: “When you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth.” We shall see.

Loading ...

Loading ...

What do you think?

You can post as a subscriber user ...

User comments (0)