According to a credible estimate, no more than 5 per cent of the art created in the Middle Ages still survives. The reasons include successive waves of religious reform, warfare, the fickle finger of fashion, neglect and decay. But as the wonderful, and free, Fragmented Illuminations exhibition at London’s Victoria and Albert Museum, explains, even people who loved, admired and imitated the artistic accomplishments of the Middle Ages and Renaissance, were more than happy to dismember medieval and sixteenth-century manuscripts.

These biblioclasts included nineteenth century churchmen, librarians, curators, thieves and even John Ruskin, the great Victorian art critic and author.

“Cut missal up in evening – hard work,” reads his diary entry for 3 January 1854. Well, that’s one way of working off the excesses of Christmas, I suppose.

The exhibition showcases a small fraction of the 2000-plus loose leaves and cuttings from medieval and Renaissance manuscripts now in the collection of the museum. It’s a collection that dates back to the founding of the museum in 1852.

At this time, the art market was awash with treasures of this sort, the consequences of decades of warfare and violent turmoil ignited by the French Revolution. Monastic and cathedral libraries across Europe were ransacked and looted.

Not even the Vatican was spared, its books pillaged by French soldiers in 1798. Although many of the resulting spoils found their way into university and national libraries, where they remain to this day, others were destined for dismemberment at the hands of book dealers and collectors.

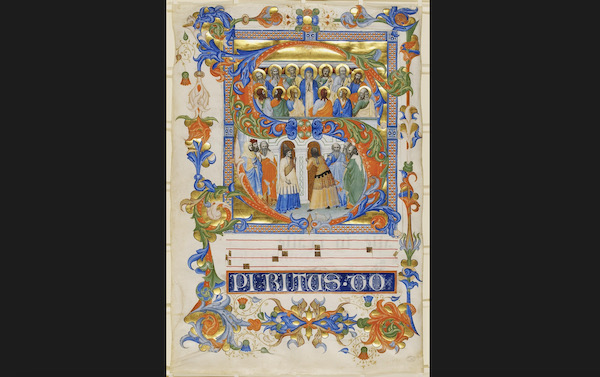

In March 1825, Sotheby’s in London held a four-day auction devoted solely to cuttings from medieval and Renaissance manuscripts. Its organiser was Luigi Celotti, a Venetian priest turned art dealer. The star lots were cuttings from early sixteenth-century papal service books. The exhibition includes a montage of fragments from manuscripts commissioned for the chapels of Leo X (1513-21) and Clement VII (1523-34). The illuminations depict the Virgin and Child, various saints, coats and arms, mottos and intricate architectural designs, all of which Celotti reassembled and pasted onto an ornate gilt wood frame in imitation of a Renaissance panel painting.

Sir John Charles Robinson, the Victoria and Albert’s first curator of ornamental art, formed a formidable personal collection of medieval and Renaissance artefacts and manuscripts. The fragments on display include initials with engaging depictions of Christ and the saints excised from a mid-fourteenth century Netherlandish manuscript. These we, are told, were acquired by Robinson in Bonn during one of his regular “shopping” expeditions to mainland Europe, where rich pickings, often at bargain prices, awaited connoisseurs of medieval book production.

Halloween is just around the corner. In the spirit of the season it’s therefore worth noting that Dennistoun’s prowess as a collector was such that he almost certainly provided inspiration for a character in what’s arguably one of the best ghost stories ever written, Canon Alberic’s Scrapbook, by Montague Rhodes James.

The main protagonist is an antiquarian called Dennistoun, who on a visit to the ancient cathedral of Saint Bertrand-de-Commignes in the foothills of the Pyrenees purchases a book, for a what turns out to be a frighteningly good price, containing leaves cut from medieval manuscripts by a seventeenth-century priest, the eponymous Canon Alberic. Was Alberic a bibliophile or biblioclast, or both? We are told that Dennistoun was “amateur des vieux livres”, or “lover of old books” and that he spoke with “a touch of the North British”, that’s to say, Scottish, “in his tone”. MR James is most famous today for his ghost stories, but was also one of the greatest scholars of medieval manuscripts ever to walk the earth and he’d certainly have been well aware of Dennistoun’s activities as a collector.

As the exhibition also makes clear, these dismembered treasures of medieval book craft were used as didactic tools for nineteenth-century craftsmen. Examples of their work, every bit as accomplished as the medieval originals, are included in the exhibition. So too are wonderfully decorated and illuminated leafs from an array medieval of service books – antiphoners, graduales, missals, breviaries – from which priests, monks and nuns sang the liturgy. You can also see pages from biblical commentaries, and medical and legal text books, the mainstays of medieval monastic and university libraries. Hats off to Dr Catherine Yvard, the curator who put together this feast for the eye and mind.

Loose leaves and cuttings of the kind included in the exhibition can be found in the collections of most major museums and libraries. They continue to be sold at auction, with twice yearly sales at Christie’s, Sotheby’s and Bloomsbury Auctions offering pages and cuttings of a type that have been traded since the Celotti auction in 1825. The scholarly sale catalogues and the diligent research of Peter Kidd for his outstanding Medieval Manuscripts Provenance blog, mean that more than ever is known about the original context of these dismembered treasures of medieval and Renaissance book production.

Loading ...

Loading ...

What do you think?

You can post as a subscriber user ...

User comments (0)