It’s the very definition of a first world problem – working out how to explain the causes, complexities and consequences of Henry VIII’s break with Rome and the English Reformation.

I know from my work at English Heritage and university teaching that the religious disputes of the sixteenth century can seem remote, baffling, even repellent to audiences in our largely secular, even post-Christian society.

But it’s a challenge I’m happy to embrace and as an art historian I rely on works of art to interpret and bring the past alive. I’d therefore argue there’s no better guide to this pivotal epoch in English history than the works of Hans Holbein the Younger (1497-1543), the great artist of the Tudor Court, his panel paintings, drawings and illuminations, as eye opening and revealing as any written document.

Often named together with Lukas Cranach and Albrecht Dürer as one of the three great propagandists of the Lutheran Reformation, his oeuvre tells a somewhat different story encompassing not only religious change but also conservatism and continuity and agonising questions of personal conscience and a contested path to the Divine and spiritual salvation.

Born in Basel in 1497, the religious world of the young Holbein was one of conventional, even thriving, late medieval piety. It was a world of saints, relics, pious works and glorious devotional imagery. This is epitomised by two extraordinary silver-gilt reliquaries which depict St Christopher and St Sebastian. They were made in the year of the artist’s birth, based on designs by his father, Hans Holbein the Elder. Containing relics of these two saints, they were commissioned by a Cistercian abbot in the hope that the saints so exquisitely rendered in precious metal would intervene on his behalf and provide protection against a visitation of the plague (I’m tempted to invoke them myself).

The precocious Hans the Younger was soon producing equally magnificent religious works of art, especially panel paintings such as the so-called Darmstadt Madonna. It depicts the Virgin and Child together with the man who paid for the painting, Jakob Meyer zum Hasen, a leading Basel citizen, and members of his family.

The painting has Holbein’s trademark realism and is a typical work of early Renaissance Catholic piety. If you look closely you can see how the Virgin’s cloak is draped over Jacob’s shoulder, an indication that she was extending her protection over the pious donor. Jakob’s daughter, in the right of the paintings, is depicted clutching a rosary, the key expression of popular devotion to the Virgin.

The painting takes on a whole other significance when you learn that it was painted in 1526 when Basel was riven by confessional strife. One faction advocated the adoption of the ideals of Martin Luther who had unleashed the Protestant Reformation nine years earlier. The other, led by this painting’s donor, supported traditional religion.

He was to be on the losing side. Basel embraced the Reformation. The contested place of imagery in the Reformed religion caused Holbein, whose own works were destroyed by iconoclasts, to migrate to London in 1526, the very year he completed the Madonna for his Catholic patron.

In England Holbein found a religious environment much conducive to the arts. In 1521, the young Henry VIII wrote his Defence of the Seven Sacraments, a stinging repudiation of Lutheranism. Holbein’s woodcut borders ornamented the book’s title page.

Holbein’s arrival in England was eased by the patronage and connections of Erasmus, the great Dutch humanist thinker – and I means humanist in its Renaissance rather than contemporary sense – whom Holbein had painted a few years earlier.

Among Holbein’s early clients was Sir (later Saint) Thomas More. A preparatory drawing for a now lost panel painting of More and his family resonates with religious significance, especially the devotional jewellery worn by his daughters and the books of hours, medieval “best sellers” and works of traditional piety, which they are shown reading.

In 1528, Holbein returned to Basel, where, after some initial reluctance and inner turmoil, he apparently accepted the reformed Lutheran faith. These decisions of conscience could come at a cost: Erasmus, Holbein’s onetime patron and friend, complained that by embracing Lutheranism the artist had “deceived those to whom he was recommended”.

Holbein returned to England in 1531/32 where the religious situation had shifted radically in favour of Evangelicals, eager to promote an agenda of reform.

The catalyst was, of course, the King’s “Great Matter”, Henry’s struggle with the Pope to annul his marriage of Queen Katherine of Aragon and marry Ann Boleyn. In 1534, Henry took matters into his own hands, repudiating papal authority, and declaring himself head of the Church of England, below Christ, as far as the law of God allows.

This key event in the English Reformation – the Royal Supremacy – was given visual expression by Holbein in this masterly work of art. In the tradition of luxury illuminated manuscripts and painted in vellum using the most expensive of pigments, it was likely a New Year gift from Holbein to Henry in 1534 – he genuinely did know how to make friends and influence people. One you understand the miniature’s complex iconography, you’ll understand why the gift would’ve warmed Henry’s heart and gladdened his soul.

The subject is King Solomon receiving the Queen of Sheba, an event described in the Old Testament. Seated on an elevated throne and the very image of power and majesty, Solomon closely resembles Henry. The stately figure of the Queen of Sheba, her back half turned as she approaches the King, was intended to personify the Church, her attendants the clergy, who had recently sworn their allegiance to Henry as their head. The Latin inscriptions, all with a biblical source, explicitly state that Solomon – Henry – had been placed on his throne, given authority from God Himself.

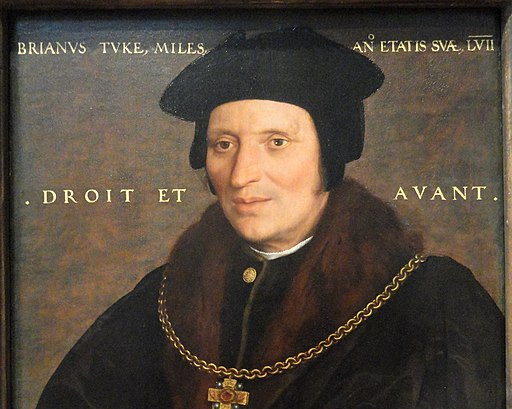

But Henry’s Reformation was not as radical as many Evangelicals hoped, and many religious issues remained bitterly contested. It’s a point well made by Holbein’s portrait of the courtier, Sir Brian Tuke, painted at around the same time as the miniature I’ve just been discussing. It’s a typical Holbein portrait. As is so often the case with his work, the details really matter, in this case the cross hanging around the sitter’s neck.

Devotional bling, it depicts the Five Wounds of Christ, an incredibly popular focus of late medieval piety and an expression of what nerds like me call Christ-centric piety. This encouraged people to form an emotional connection with Christ’s suffering for the redemption of humanity. It makes clear that much of Catholic England’s traditional devotional culture initially remained unaffected by Henry’s break with Rome.

Nevertheless, the King’s Reformation nevertheless provoked bitter opposition, even outright rebellion. In 1536 much of northern England participated in an uprising called the Pilgrimage of Grace. Its causes included Henry’s assault on traditional religion, and the dissolution of the smaller monasteries which was then in full swing. Significantly, the Pilgrims rallied beneath a banner and wore badges depicting the Five Wounds. As was so often the case with Henry, art was political.

Holbein’s work also evokes the spiritual excitement, the sense of agency which the Reformation provided for many. For instance his Allegory on the Old and the New Testaments, painted in 1533-35. It asserts the central tenet of Lutheran theology, that salvation is achieved through faith in Christ alone.

However, the Henrician Reformation more often entailed the destruction rather than the creation, of works of art. Henry also destroyed lives, and Holbein has given us likeness of many of those who suffered and died because of their consciences or Henry’s caprice: the Catholic martyrs St John Fisher of Rochester and St Thomas More and advocates of reform such as Queen Anne Boleyn and Thomas Cromwell.

Holbein’s skill was such that we’re able to gaze upon the faces of recognisable individuals with whom, even after the passage of half a millennium, we can identify, even empathise. For me, forging an emotional connection with the people who lived through and shaped this turbulent era is central to untangling its complexities and bringing it alive.

Loading ...

Loading ...

What do you think?

You can post as a subscriber user ...

User comments (0)