Christmas plans in ruins after Boris’s bombshell? Well, spare a thought for the Cistercian monks of Hailes Abbey, who on Christmas Eve 1539 appended their signatures to the deed “voluntarily” surrendering their monastery to Henry VIII, an act which quite literally led to the ruination of their abbey.

History doesn’t record how the dispossessed Hailes monks spent their first Christmas after being expelled from the cloister. But there’s plenty of evidence showing how sacred observance and secular celebration of the festive season found itself on the front line of a fierce early modern culture war. Between the sixteenth and eighteenth century, the Twelve Days were besieged by the twin forces of religious and moral reform. When it was all over, a battered, diminished Christmas really did need its Victorian makeover.

By then it was a far cry from the sacred and secular splendour of the last medieval Christmas when, in elite households, the season was given over to feasting, entertainment, sports and gift giving. Christian charity meant that the poor were able to enjoy some of this festive cheer and the obligations of hospitality meant that many a lord, bishop and abbot kept open house in his great hall, receiving all comers as is they were Christ Himself. Indeed, failure to adhere to standards of “good lordship” could lead to a loss of honour, a prized commodity among the ruling elite of late medieval England.

All this started to change in the mid-sixteenth century, when religious sensibilities – Catholic and Protestant alike – and manners started to be thoroughly reformed. By the end of the eighteenth century, for the ruling elites and emergent middle classes especially, Christmas had become distinctly unfashionable and a bit of a bore. The merry making was condemned as vulgar, the indiscriminate charity as morally questionable (what would the undeserving, feckless poor spend that ha’penny on?) and the mixing of the social classes was quite frankly horrific.

But not everybody was prepared to abandon their Christmas celebrations without a fight. Over quarter a century ago I assembled evidence contained in the diaries, “commonplace books”, letters and financial accounts of several northern English Catholic gents, who between the late-sixteenth and mid-eighteenth centuries, in the face of religious oppression, financial penalty and social change, maintained many of the conventions of the late medieval Christmas.

Some captivating gleanings are provided in the memorandum book of Richard Cholmeley (1570-1624) of Brandsby, North Yorkshire. His Christmas celebrations resonated with the traditions of an earlier, unambiguously Catholic age. His great hall was decked with greenery on Christmas Eve, functioning over the Twelve Days as what modern historians call a “theatre of hospitality” for Cholmeley to display his largesse. Charity was dispensed to the poor. Feasts with musical accompaniment were held throughout the Christmas season, the guests including Cholmeley’s tenants and neighbouring gentry. Proceedings were kept merry by wine and spices bought in York.

In 1618, one of the guests over indulged on the free booze, picking a fight with Cholmeley’s bailiff, drunkenly shouting: “Kiss my arse, shitten Harry!” Like a good pub landlord today, Cholmeley sought to defuse the situation by appealing to festive goodwill, intervening with the words: “It is not fit to reckon up wrongs or griefs but to be merry.”

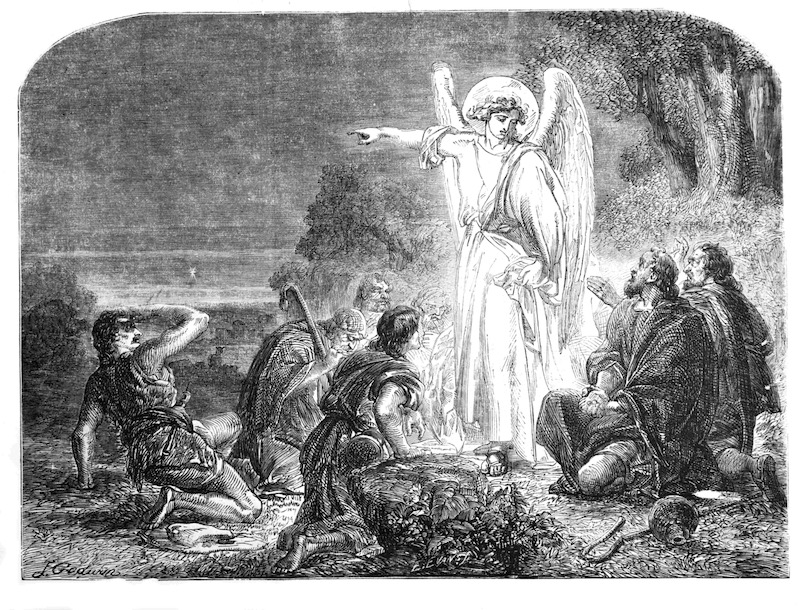

A generation later in 1647, William Blundell (1620-98) of Little Crosby, near Liverpool, defiantly celebrated the Twelve Days in the hall of his manor despite having po-faced Parliamentarian soldiers billeted on him. Let’s not forget, this was a time when public observance of Christmas was banned by the Puritan authorities who would even force their way into homes if they suspected something resembling festive fun was taking place.

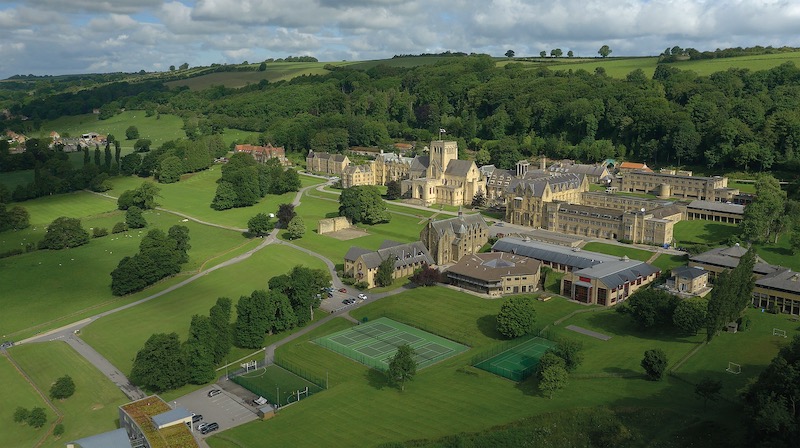

Fifteen years later, the Constables of Everingham Park entertained their co-religionist friends, neighbours and tenants to a slap up Christmas feast. At around the same time, Sir Thomas Haggerston (1627-1709) in rural Northumberland and Sir Miles Stapleton (1628-1707) in the West Riding, marked the Christmas holidays with feasting, piping, plays and the distribution of gifts to the local Catholic poor.

Such traditions were maintained into the eighteenth century. Nicholas Blundell (1669-1737), William’s heir at Little Crosby, clearly enjoyed his Christmas cheer. He hosted “merry nights” for tenants and posh friends alike in his greenery-bedecked, hospitable hall and even performed a few card tricks for the amusement of his guests. Blundell was mindful of his charitable obligations, distributing bread, ale and cash to the indigent at his gate. Blundell, accompanied by his lady wife, visited the tenantry in their homes and wasn’t above sharing their “Christmas cheer”. His close contemporary, Roger Strickland (1680-1749) of Richmond, Yorkshire, also his Christmas tucker, buying expensive provisions including a boar’s head, the most luxurious of Yuletide fayre and a fixture in elite households since the Middle Ages. He was also prepared to put aside his high birth, mixing with all comers during the games and sports that accompanied Christmas and the other major religious feast days that punctuate the year.

However, Strickland and his fellow recusant gents weren’t impervious to the religious and social forces that eroded observance of the historic Christmas. In older age, both Blundells spent their Christmas Days reading an edifying spiritual book rather than making merry in their hall. Catholics were just as eager as their Protestant neighbours to polish their manners and keep “polite” company in assembly rooms.

Nevertheless, there’s a remarkable continuity in the Christmas celebrations of these posh northern Catholics – and we’d recognise many of them today. Held at a dark, cold time of year, the festival honouring Christ’s birth was one of joy, plain old fun and a bit of licensed misbehaviour.

But their Christmas observances also had deeper meaning. The communal feasting, charity and rites of hospitality asserted an attachment to notions of lordship which helped maintain the ties that bound a rigorously hierarchical society together. A bit of hospitality, charity and sharing a pie and a pint with the tenants helps defuse some of the tensions inevitable in such an unequal world – indeed, the Victorian revival of Christmas was partly because they needed some glue with which to bind their industrialised, unequal and frequently cruel society.

Maintaining the medieval cycle of the Twelve Days was a defiant expression of English Catholics’ religious identity, for which all the gents discussed here were punished by the State to some degree.

So, there is evidence that Christmas can survive even the most adverse of circumstances. If William Blundell could have a jolly Christmas while being an unwilling host to Oliver Cromwell’s heavies, I’ve every confidence that, even in the face of Covid and its tiers and tears, we can too. A merry and safe Christmas to you all.

Loading ...

Loading ...

What do you think?

You can post as a subscriber user ...

User comments (0)