In the last few weeks Zambia has fallen into a debt crisis. The country has officially defaulted – in other words it can’t cough up to pay off its foreign lenders. There’s now a real risk of contagion with a wave of defaults expected in other developing countries.

The spread of Covid-19 is destroying developing countries’ economies, leaving millions of people faced with loss of jobs in the informal economy as markets shut down, pushing families to the brink of hunger and extreme poverty.

Research by the Johns Hopkins Medical School looks at how the virus is disrupting health systems and concludes that daily, an additional six thousand children could die from preventable diseases.

So, what can be done?

This is clearly an emergency situation and UK aid agencies such as Cafod are doing the immediate humanitarian work in providing food and improving hand washing and sanitation facilities in communities and households.

But that’s not going to be enough to deal with the unprecedented economic chaos.

Developing countries need to be able to immediately renegotiate their debts and have debts cancelled – otherwise how are they going to afford a vaccine and the equipment to distribute it?

Currently, the G20 has helped around 40 developing countries suspend some of their debt payments and the IMF has written off around $450 million.

The problem is that even if a developing country is getting some of this debt relief – and for many it’s a big if – it’s probably being snatched away again to pay off private lenders in London and New York.

Up until now the G20 has failed to reach agreements that would stop private banks like HSBC and asset managers like BlackRock from profiteering off the backs of the world's poorest people.

Former Prime Minister, Gordon Brown wrote in a recent article in the Guardian that, private creditors hold a lot more developing country debt than they did 20 years ago so they can’t be left out of any G20 agreements on the debt crisis.

The UK is one of the G20’s member governments. It’s in a unique position because a lot of developing country debt is covered by UK law. To stop the profiteering the UK government could pass legislation preventing private lenders from suing developing countries if they wanted to renegotiate their debts or receive debt relief.

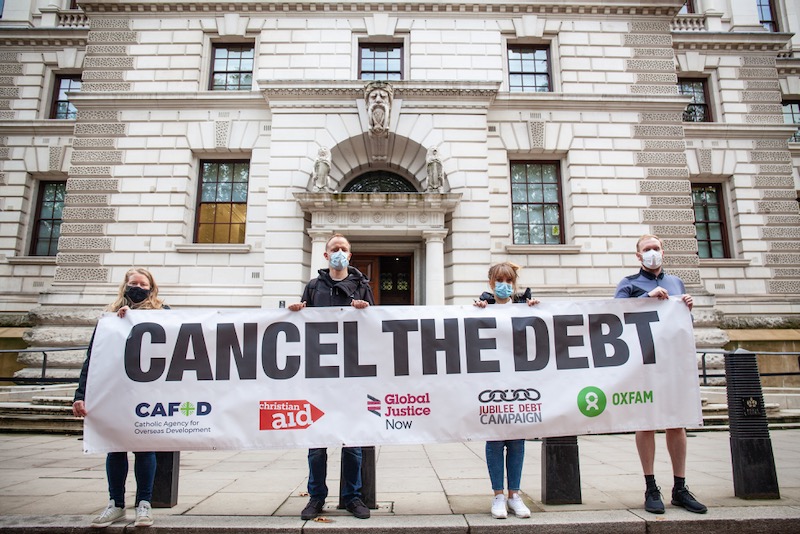

In a recent report Under the Radar, CAFOD along with other UK aid agencies, calls on the G20 to compel private creditors to suspend debt payments and write-down developing country debts. Without coordination at the G20 and changes to UK law it’s basically like saying: you have no money and you’re trying to tackle the spread of Covid-19 - good luck Zambia!

The Zambian government has been pleading with their private lenders to accept a six-month debt payment holiday, but in October not all of the creditors bothered to turn up to a meeting, and just last week they voted against it. How can the Zambian government get these private creditors around the table?

This weekend the G20 is meeting and is expected to make progress on a framework that would enable developing countries to talk to their lenders. However, it probably won’t put in place measures that actually, oblige private lenders to reach a quick agreement on sorting out debts.

This means that countries like Zambia just stay in limbo for longer. The longer the process takes, which should involve debts being cancelled, the longer the government can’t confidently redirect its budget towards fighting the pandemic and rebuilding the economy.

But colleagues in Zambia point out if debts are cancelled that’s not the end of the story because of the government’s lack of effective debt management. So, strengthening democratic mechanisms to oversee public finances and transparency about who the government borrowed from and how funds have been are fundamental.

The Jesuit Centre for Theological Reflection (JCTR) is a Zambian Think Tank, on economic development and poverty analysis. Its executive director, Father Alex Muyebe, told me it’s vital that Zambians “take it upon themselves to demand accountability and involvement in coming up with a roadmap of how our country is going to pull itself out of this undesired and dangerous debt crisis.” He concluded: “So that we shall never fall in such perilous indebtedness again.”

Dario Kenner is Cafod's Lead analyst in sustainable economic development.

Loading ...

Loading ...

What do you think?

You can post as a subscriber user ...

User comments (0)