There are moments that punctuate history in such a remarkable way that they transform the imagination. Be it, the destruction of the Berlin Wall and the reconstitution of a democratic united Germany, the release of Nelson Mandela and ending of apartheid or on a much more negative level the events of September 11th. These historical acts not only change the way a country or a people are viewed, but they change the way in which those within see themselves and imagine themselves to be within their own futures. The Bible is no different. Moses' Exodus of the Israelites or David's restoration of the twelve tribes of Israel transformed a national psyche but also on a purely existential level, changed the dreams and aspirations that those individuals had of themselves. All of these moments or epochs make us question our reality, but also make us feel alive to the world around us - in both positive and negative ways.

Take for example John's account of Jesus interaction with the woman who had committed adultery (notice they didn't bring the man). The Pharisees ploy to catch Jesus out and quote the Law is diffused by his response, “Let anyone among you who is without sin be the first to throw a stone at her." A moment of antagonism is diffused immediately, like it or not, their imaginations are captured and they walk away considering their own judgemental lives. The woman herself, is forgiven but not let of the hook, “Neither do I condemn you. Go your way, and from now on do not sin again"; her life transformed through mercy and compassion. She moves from isolation to freedom, with a sense of renewal and a reimagining of her own life.

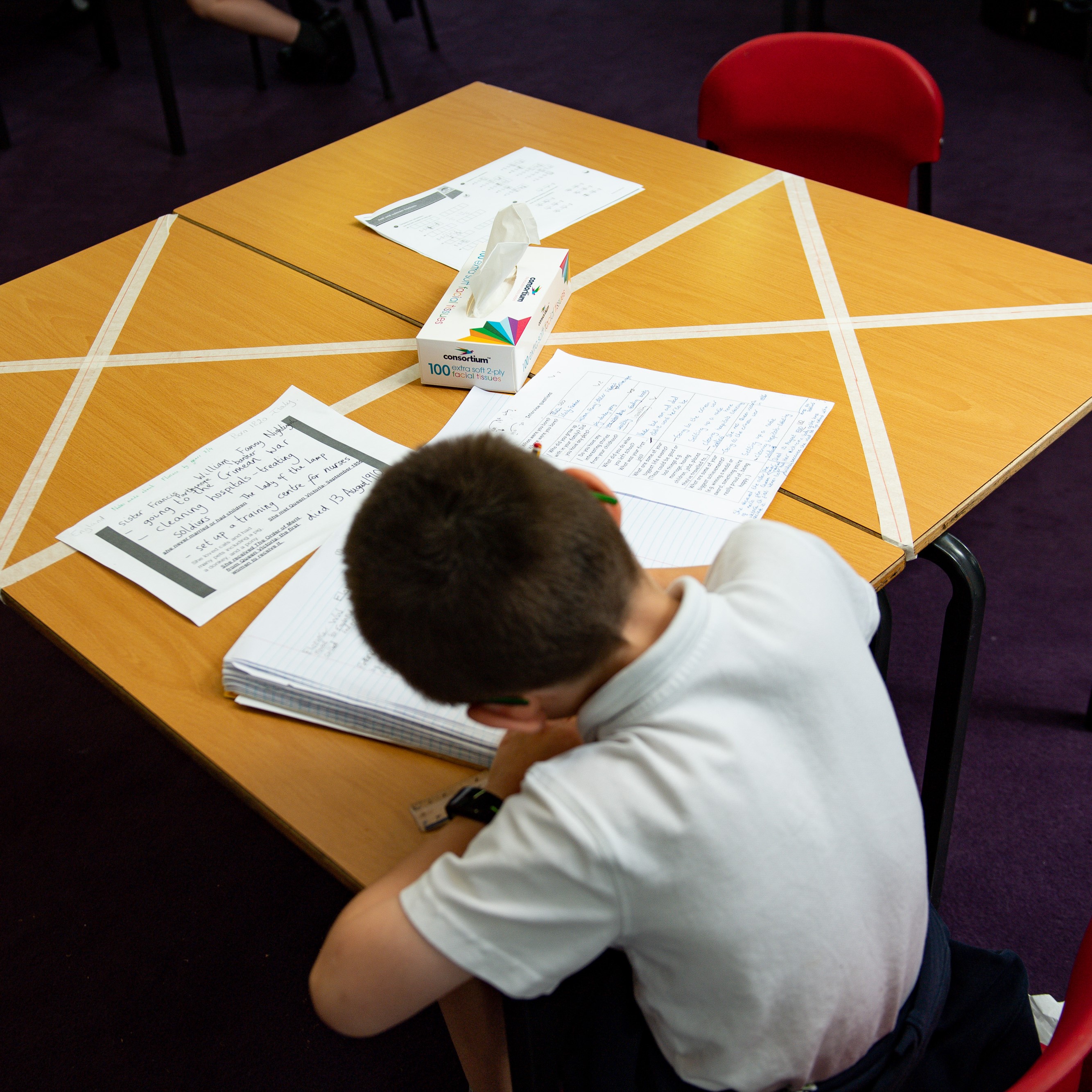

The word 'imagination' is often considered as the creative power of the mind that builds a picture or mental concept of oneself. The term itself comes from the Latin verb imaginari which means to 'picture oneself' - this can often take place in both positive and negative forms, but on the whole, when we imagine and daydream, we tend to think of ourselves in scenarios that show the best of a future capabilities - our best side. In some ways, the Covid-19 pandemic bears a strange similarity. It has changed the way we communicate with one another, interact with society and finally, and even more importantly, how we educate our children. During lockdown, schools have done remarkable things, often with very little notice, to set up running their provision from home and finding imaginative ways to engage and entice students into learning. Across the educational landscape, I have seen and read about schools doing incredible things with teachers developing and harnessing new IT skills and creative ways to teach their children. All too often the media focus has been on unions and lambasting teachers with the perception that they do not want to come back into schools, but that couldn't be further from the truth in my experience. Whilst all of these new initiatives have been great, they are in some ways novel. They are also not sustainable for the long term education of children. The simple truth is this: nothing can replace the teacher stood in front of their class capturing the imagination of their classes on a daily basis. The sense of awe and wonder, learning new facts, forging new opinions - all of which come through the magic of being in a school. Schooling is also much more than lessons in classrooms - it is also about the formation of the human person and as St Irenaeus wrote, "The Glory of God is the human person fully alive." Is anyone fully alive whilst learning or socialising on Zoom?

In a school, the rich tapestry of community is inescapable; the sense of camaraderie amongst staff and students is so often one of the key driving forces behind the most successful schools. It is important for us to remember that schools are places built on relationships that require the need for daily dialogue and interactions. This couldn't happen in the same way during the school closures. For example, on our feast day of All Saints last November, our staff lined up along the entrance into the school and sang 'When the Saints go marching in' accompanied by students playing steel pans as all our young people marched in. At first, some were embarrassed, but they walked in and most turned and tagged onto the staff line and joined in with the singing. Moments like this in schools are ineffable and impress upon the imagination as a time to remember. Alas, in the current climate, it would be difficult to replicate this act, but therein poses the new challenge that faces us all. How do we recapture the imagination of children as they re-join school in September?

At present school leaders are fine-tuning their risk assessments and laying the plans of necessary measures within school that keep children safe and stop the spread of this virus and of course, when students return there is much-needed work to be done on assessing and evaluating how they have coped and where they are at in their learning. But if that ends up being the sole focus of schools over the next six to eight weeks, we run the risk of drifting through September in the transitory state of merely finding out what happened - this would be joyless, mainly for the pupils. When we return, the imaginations of teachers and staff members need to be brimming with enthusiasm to bring students back into the fold and reawaken their sense of community and their value within it. Last November, I looked with my Leadership team at some research and statistics about reading. It was startling to see that the levels of teacher-led reading tailed of so much from primary into secondary school, and not only that, how much national trends showed a decline from Early Years into Key Stage 2. We decided to add an additional lesson into the curriculum where the sole focus would be on teacher-led reading for every child in Year 7 to 9. This lesson would focus on reading a book of fiction, linked to a subject area that would allow students to build up a greater understanding of the subject, but also stir their imaginations. My hope in September is that this research-based initiative will not only further foster a love of reading, but allow students to understand parts of their taught curriculum by delving into the world of literature and letting their imaginations run wild.

But in reality it is not just about the taught curriculum; of course, it isn't. Of fundamental importance will be the need to tap into the things that students have not been able to access during their absence from school; their extra-curricular clubs and activities, the musical performances, the sports teams. This is where teachers up and down the land will shine, they will be delighted to welcome the children back that they haven't seen for the best part of six months. These are the moments, for students, that punctuate their school life and can truly capture their imaginations. In September, when we return, the aim is to make our young people feel fully alive again, that will truly be the glory of God.

Andrew O’Neill has been the Headteacher of All Saints Catholic College (formerly Sion-Manning Catholic Girls’ School) since 2016. Since that time, the school has gone from being on the brink of closure to become highly over-subscribed and developed a reputation for offering quality education.

Loading ...

Loading ...

What do you think?

You can post as a subscriber user ...

User comments (0)