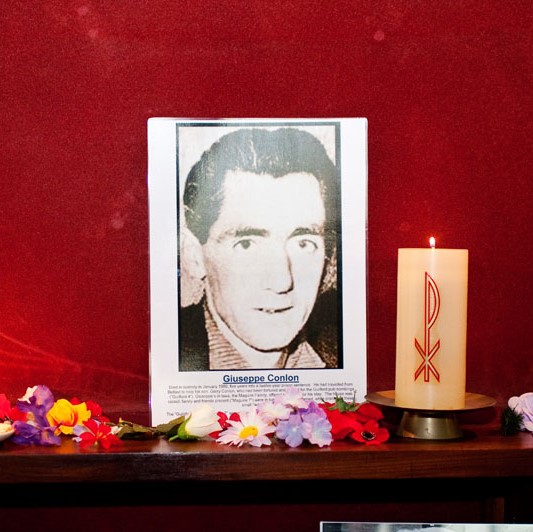

Giuseppe Conlon House is a House of Hospitality, under the umbrella of the Catholic Worker movement, which welcomes destitute asylum seekers, and is run broadly on Dorothy Day and Peter Maurin's Christian anarchist principles.

Christian anarchism is, broadly speaking, the devotion to a type of serving Christ that rejects the idea that the state can be fully accepted and co-operated with, particular given Jesus' apparent contempt for the ruling classes of the Roman Empire. Despite this, not everyone who lives in Giuseppe Conlon House would refer to themselves as "Christian", or as "anarchist", least of all "Christian anarchist". It's a healthy plurality of people devoted to Giuseppe Conlon House's essential mission of supporting the most marginalised people in UK society.

I lived in Giuseppe Conlon House many years ago – and I still feel strongly connected to its essential values. When I lived there, there were twenty no-recourse to public funds and, for most of the time I was there, only four live-in volunteers. As someone who likes to empathise, and to listen, this was a huge challenge for me and I remember sensations of incendiary burnout from living with so many vulnerable people and wanting to help more than I could. Yet I also remember the most spiritually and emotionally enriching experiences in my life: of growing in ways I never knew were possible.

It was perhaps the memories of enrichment, and not burnout, that encouraged me to return to Giuseppe Conlon House last month during the Covid-19 pandemic. Before the pandemic hit, I was couch-surfing in Manchester and tutoring English, as well as writing sprawlingly. I had an intuition that the pandemic would be altering unrecognisably the whole nature and composition of Giuseppe Conlon House. I had an intuition, also, that concerns about homeless people would be a significant yet marginal issue during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Needless to say, when I returned to Giuseppe Conlon House, they were in the process of putting the guests, the term we refer to use to the homeless people that live with us, in emergency accommodation throughout London. This is something I'd seen pasted across the news and I hadn't connected the dots. I suppose I developed a key role in this, and the uncertainty of the process – and how it displaced Giuseppe Conlon House – was extremely dramatic. Many of the guests wanted to go to the emergency accommodation and couldn't, because they were outside the high risk category. Many of the guests didn't want to go to emergency accommodation but it was decreed that it would be best for them.

In addition, like most homeless shelters, guests are normally supposed to leave during the day, unless they have a formidable excuse. The fact that, as a direct opposite, they could not now leave during the day and their full presence was encouraged had temporarily created a feeling of togetherness. Then we watched this togetherness disintegrate as some guests were moved into hotels throughout London, whereas some were not. These circumstances were beyond our control, and part of a set of mechanisms that had been triggered before my arrival, so it was particularly unusual for me to implement them, when many of the other live-in volunteers here fell ill with probable Covid-19.

This included a visit from a triage doctor, who assessed the guests' medical histories in record time upon the sanctuary of our church, calculating what their fate will be in this new era. It was a striking counterpoint to the normal rhythms of Catholic Worker communities: an image that will stay with me always. Homeless people were quickly, but necessarily, reduced to batteries of symptoms, ensuring they can have the temporary dignity of a makeshift room for themselves, or they must contend with their presumably greater exposure to the virus in Giuseppe Conlon House. As an operation manned by organisations we have no major insight into, we were distinctly powerless.

This powerlessness lived with us as we tried to work out how to adapt Giuseppe Conlon House to the new coronavirus paradigm. While people are more generous than ever, exactly how we distributed the food donations we received became a paramount concern. In addition, the community, which I have only ever known bustling with life and ceaseless activity, save on those rare occasions in which it is closed, became exponentially reduced in its activities. Yet we had to reason that the levels of activity and bustle that we were attuned to were impossible to maintain in this climate. It occurred to me that we cannot save everyone, and that we can use this time to "go inward", rather than constantly heading "outward".

For Giuseppe Conlon House to "go inward" is a huge leap. Our entire space, and all of our networks, are designed around the fact that the community is composed of about the most "outward" people who exist. This is reflected in the way they are surrounded by the most vulnerable people. This is not a centre, a shelter, or anywhere else that is not a totally integrated space. The volunteers socialising only with each other over meals, which, in practically every religious community in the UK, is very normal, definitely feels like an anomaly. So does having more time for prayer, contemplation, meditation, and enjoying cooking and gardening without the usual convulsive energy of the house as a backdrop.

Yet, one supposes that if GCH can go inward, any religious community can. One supposes also that there is a huge number of religious communities which have had to radically re-explore what they do, and that this is an issue which nobody has paid attention to. What happens to "religious" communities during a pandemic? Are they households, or workplaces? This is an issue rendered pertinent by the many members of religious communities who have died after contracting Covid-19. One of these was Fr John McNamara, a Northern Irish Carmelite priest who contracted Covid-19. Such deaths lead us to ask, powerfully: what has happened to religious communities in this time? How will they transform?

The London Catholic Worker has been based in Giussepe Conlon house since 2010. You can follow them through their website, facebook page, or twitter.

Loading ...

Loading ...

What do you think?

You can post as a subscriber user ...

User comments (0)