By Father John Jairo SJ

By Father John Jairo SJ

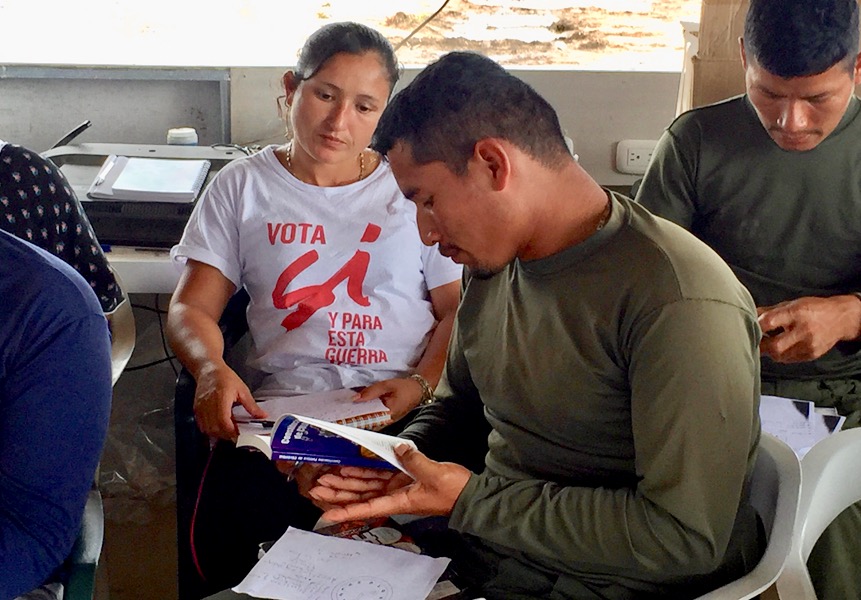

I had never come face to face with a member of the FARC until I visited one of the 26 transition zones where fighters are demobilised under Colombia’s revised peace agreement, signed a year ago. My task was to teach them about basic constitutional principles, human rights and political participation.

It was the first time in their lives they held in their hands a copy of Colombia’s constitution. Afterwards, one woman came up to me and said “Hey, I have rights. As a woman I have rights, and my children have rights!” Having been in the ranks of the FARC for years, she didn’t realise the wealth and strength of Colombia’s laws and constitution.

The Colombian organisation I work for, the Centre for Popular Investigation and Education (known by its Spanish acronym, CINEP), supported by UK aid agency CAFOD, tries to bridge the gap between those excellent laws and the reality of their poor implementation. CINEP promotes human rights, and is playing a key role monitoring Colombia’s peace agreement.

These war-weary fighters are mostly peasant farmers, coming from the most deprived regions of the country: places barely touched by the state’s presence during more than five decades of armed conflict.

Despite the toll of the war, and doubts about the government’s fulfilment of the peace agreement, they hope for a better future. Now they want to change their lives. When I asked them, “What is next?”, they told me they wanted to get married, raise children – in short, live an ordinary life like anyone else in the country. If we as civil society don’t help them to achieve their dreams and desires, there will be little hope of preserving the peace.

Over the past 12 months, my country has seen positive changes, including a fall in armed conflict. But it will take a long time for normality to return. Not all FARC members have agreed to demobilise – around 10 per cent are still active, many involved in drug trafficking. And, though most community leaders and human rights defenders support the peace agreement, they are paying for it with their lives.

In October last year José Jair Cortés, a 41-year-old local leader and human rights activist, was murdered near the city of Tumaco, in south-west Colombia. José was educating people about the dangers of landmines, and repeatedly spoke out about violence from various armed groups in the region. He is just one of the latest activists to be killed in what continues to be one of the most dangerous countries to defend rights: in the first six months of 2017, more than 51 social leaders and human rights defenders were killed, according to Colombian non-governmental organisation Somos Defensores. A viable peace agreement demands that the Colombian Government must guarantee the safety of people who work for peace or enter politics.

One woman on the course told me her family was killed when she was young. She joined the guerrillas, and they became her family. Some women joined to escape the situation at home: many had been raped, or suffered violence by family members. In the movement, people called each other by their alias. Even in the transition zones, where they eat, sleep and make friends, they often don’t know each other’s real names.

At the end of the course I asked for their birth names, so I could give them certificates. For many it was the first time in years that they had used them; as they started to share their names, they began to laugh and joke. War gave them one personality, and now they face the challenge of rebuilding their "new" identities in the outside world, without their combat fatigues and guns.

At the end of the course I asked for their birth names, so I could give them certificates. For many it was the first time in years that they had used them; as they started to share their names, they began to laugh and joke. War gave them one personality, and now they face the challenge of rebuilding their "new" identities in the outside world, without their combat fatigues and guns.

It is too early to say if the peace agreement with the FARC has been a success. The focus so far has mainly been on demobilisation and disarmament – just one of the six points covered by the peace agreement. The remaining five – rural reform, political participation, victims’ rights, and ratification, implementation and verification, all areas where the state must take the initiative – have not yet begun.

Our Government faces big challenges beyond dismantling paramilitary structures. It must address the unequal distribution of land, a major cause of the conflict, and help former guerrillas in the transition to a normal life, guaranteeing their safety and the long-term viability of their new lives. It needs to unite all sectors of society and consider targeted policies, such as schemes to help vulnerable people into education or work. All this will take time, especially since Colombia’s state institutions are like large elephants – heavy and slow – and fail to make decisions which consider the whole picture.

My work at CINEP keeps my faith alive in the sense that I can help others build changes in their lives. When I wake up in the morning I have hope that I can contribute something for my country. We call on the international community to continue to support Colombia and the community leaders in their efforts to build peace. The risks can be high in Colombia, but as Pope Francis says, we must take our faith and ‘go out into the streets’, not keeping it silent, but making it something real, concrete, and a positive impact on people.

Father John Jairo Montoya is a Jesuit priest for CINEP's programme for development and peace in the Magdalena Medio region of Colombia, in a project accompanying victims of the armed conflict. He is currently part of the human rights team at CINEP. Follow them on Twitter.

Pictures:

1. Top pic: Colombian people gather in a FARC concert after Colombia's FARC rebel group transformed into a political party with it's new name ''Common Alternative Revolutionary Force (FARC)'', in Bogota, Colombia on September 1, 2017. Picture by: NurPhoto/SIPA USA/PA Images.

2. Father John Jairo SJ

3. Former combatants receive their certificates after a three-day course on human rights and political participation in Antioquia, Colombia. Credit: CINEP

4. A former combatant holds the Colombian Constitution. Credit: CINEP

Loading ...

Loading ...

What do you think?

You can post as a subscriber user ...

User comments (0)