Robert Mugabe had been in power for the first of his 37 years as ruler of Zimbabwe when I first saw him late in 1981 at a Zanu rally in a Harare township.

There had by then been two unusual deaths of people close to him. His brother Albert had been found dead in a swimming pool – an incident Mugabe referred to three years ago in 2014 when his nephew Takudzwa Goroonga, 20, was found dead in a cupboard in his student digs in South Africa. Mugabe referred to his nephew’s death as “a mystery” and compared it to the unexplained death of his half-brother Albert in the first year of independence. Albert was a highly popular trade union leader.

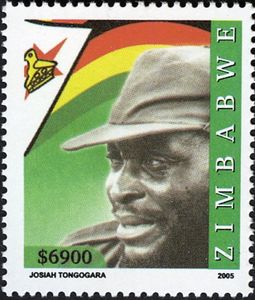

On 26 December 1979, shortly before the independence elections of the following year the commander of Zanla, the military wing of Mugabe’s Zanu party, had died in a mysterious road accident in Mozambique. Expectations after the Lancaster House conference where Josiah Tongogara was an influential participant, were that Tongogara would be the first president of independent Zimbabwe and Mugabe first prime minister. No autopsy results or pictures of the accident were ever released.

Mugabe had assured the world on taking office that the necessary Africanisation process in the newly independent country would be carried out in an orderly and fair manner. Whites from the old Rhodesian order would be replaced voluntarily by well-qualified blacks. The economy, in robust health despite years of sanctions under Ian Smith, would not suffer. The world, and the country's whites, breathed a sigh of relief. It would be some years before Tongogara had one of Harare’s lesser avenues named after him. In 2005, he was honoured on a Zimbabwean stamp.

In 2005, Tongogara was honoured on a stamp ©Twitter

In 1981, at the time of the rally, I had recently arrived in the country to teach English, keen to help build the new non-racial Zimbabwe. I went with a black neighbour, who had told me about it, and promised to translate for me from the Shona that was the likely language of address, given the venue.

I was mildly surprised to find myself just about the only white person in the assembly of 10,000 or so, but was regarded with only mild suspicion by the security personnel who let me in.

The arrival of the leader's ostentatious cavalcade at the stadium did not quite evoke the egalitarian rhetoric that had helped bring Mugabe victory the previous year, but what gave me greater pause was my neighbour's translation of Mugabe's repeated rallying cry during his hour-long speech. “Zanu will rule for ever!” he repeated, over and over again. He had not, so far as I knew, said this in any of his many interviews in English. Conveniently, his fluency in both languages enabled him to tailor his message to his audience without being easily caught out contradicting himself.

Last Sunday's expulsion of then President Robert Mugabe from the party he led for more than 40 years, whose spirit he believed he embodied in his own person, brought back that day to my mind. His loss of all status in Zanu PF, even for someone as immune to self-contradiction as Mugabe, must have been a shattering blow, as his rambling appearance on ZTV on Sunday evening showed. His audience had been expecting to hear him announcing his decision to resign then, but his mind apparently flipping into serious denial, he said he would preside over the party congress in December.

When the electorate turned on Mugabe from 2000 onwards, he turned on them. The deeper the poverty they were mired in, through his ruinous economic policies and what was by now a well-established kleptocracy, the more opulent his own lifestyle became. He boasted of his readiness for violence. He said with the disingenuousness that was always one of his hallmarks, that true Zimbabweans would be happy to live on sadza (the national maize meal-based staple), because for them their patriotism came first and they could make sacrifices.

His revenge on the people had by now included letting so-called “war veterans” loose on the country’s white farmers. Some were beaten badly, some were killed, nearly all were driven from their land, which was then handed to Mugabe’s cronies. The country’s agriculture has never recovered and a land that could easily feed itself and export to its neighbours has been reduced to dependency on food aid.

In 1983 I met Mugabe personally. With the Zimbabwean children I was teaching, I had written a play, a kind of black Romeo and Juliet, that made gentle fun of some Shona customs, in particular the paying of lobola to a bride's family. I knew by now that this was a common source of social friction, and was able to double-check plot and jokes with my black teenage students. My headmaster had the idea of inviting the prime minister, as Mugabe then was, to came and see the play. He agreed.

He arrived with only modest security and when we chatted during the interval he was polite and complimentary but did not refrain from correcting me on a point of Shona culture. I had made the father of the heroine demand lobola from the hero's family. “That would never happen,” he told me firmly. “Never.”

According to my students it certainly did happen, but his deep and genuine pride in Shona culture and customs was evident, and, I thought, was to his credit. Before leaving, however, he asked for the cast to assemble on the stage. Keeping his back to everyone else, he addressed them at some length in Shona about how to be a true Zimbabwean.

What I did not know then was that, even as we spoke, the North Korean-trained Fifth Brigade - under the jurisdiction of Emmerson Mnangagwa, who was Security Minister in charge of the Central Intelligence Organisation at the time and is poised to take over from Mugabe - was pacifying Matabeleland. The region is home to the Ndebele people, who make up 20 per cent of the population; the other 80 per cent are Shona. Joshua Nkomo’s PF-Zapu was the other section of the Patriotic Front and many of its fighters and politicians felt they had been ignored in the distribution of the spoils after independence. The campaign against these “dissidents” came to be known in Shona as “gukurahunde”, or the sweeping away of the chaff. An estimated 20,000 people were slaughtered. A report on the campaign was painstakingly assembled by the Catholic Commission for Justice and Peace in Zimbabwe and the Catholic Institute for International Relations - which subsequently became Progressio and has now folded but was not published. It finally appeared in 1997, but in such a low-key way it has received little attention.

Many details have emerged however, along with the skeletons that have come to the surface over the years. One particularly chilling detail relates how the Fifth Brigade militia would oblige relatives to dig the graves of their murdered loved ones, then force the relatives at gunpoint to dance on the graves of those they cherished, chanting pro-Mugabe slogans.

Over the next five years with the neutralising of Nkomo and his assumption of the executive presidency, Mugabe’s personality cult became ever more extravagant, his portrait ubiquitous out in the streets and inside in the workplace. I started to work as a subeditor in the evenings on The Herald newspaper - a government mouthpiece then as now, although there was, unlike today, no independent source of printed news. I learned about the day-to-day management of news in a de facto dictatorship.

Then in 1988 Pope John Paul II came to visit. Up to 10 per cent of Zimbabwe’s 13 million people are Catholic. Mugabe’s Catholicism was well known, and in the conversations with army generals that led up to his resignation he was accompanied by his confidant of several decades, Fr Fidelis Mukonori. For the past 10 years however – since the publication of their pastoral statement “God Hears the Cry of the Oppressed” in March 2007 – the Catholic bishops have bravely maintained a highly critical stance towards Mugabe and the Zanu PF government. “As the suffering population becomes more insistent, generating more and more pressure through boycotts, strikes, demonstrations and uprisings, the State responds with ever harsher oppression through arrests, detentions, banning orders, beatings and torture,” the bishops stated.

Mugabe meets Pope John Paul II in 1988 ©Twitter

But there was no such open opposition in 1988. The avenues of Harare were decorated, tall lamppost after tall lamppost, with alternating images of the Pope and of Mugabe, in a calculated display of equivalence. I was not Catholic then, but decided to go and see John Paul II and hear what he had to say. I wondered what his first words would be. With my family, I joined tens of thousands at Harare’s Borrowdale racecourse.

Mugabe was in the front row with his mother. The Pope got up to speak. “The Lord is my Shepherd!” he intoned in his unmistakeable Polish accent. It was suddenly clear to me why I had come. There was Mugabe, shepherded by I knew not what, though he certainly seemed to have made some sort of bargain with evil. And here was the head of the Church saying, it’s not about me, it’s about the Lord, who is my guide and protector. In that moment, I understood Christianity for the first time.

The following year, 1989, saw the collapse of Mugabe’s allies, the communist regimes of eastern Europe, in no small part thanks to St John Paul II. So far the fall of Mugabe has been as bloodless as the Velvet Revolution or the fall of the Berlin Wall. But as far as a free Zimbabwe any time soon is concerned, I wait and see. Mugabe said Zanu PF would rule for ever. It hasn’t gone yet. And Emmerson Mnangagwa is in charge.

(Pic: Zimbabwe Defense Forces Chief Constantino Chiwenga speaks in a press conference in Harare, Zimbabwe. Credit Xinhua/Shaun Jusa/PA)

Loading ...

Loading ...

What do you think?

You can post as a subscriber user ...

User comments (0)