Intrepid and resourceful, missionary priests had a purpose:?to travel to the most remote and far-flung places and peoples of the globe to spread the message of Christianity. But in the process, some of them, several of them Jesuits, made a contribution to the mapping of the world that rivals the work of giants in the field, such as John Speed, Gerard Mercator and Sir Robert Dudley.

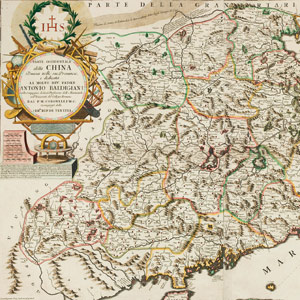

Vincenzo Coronelli was born, probably in Venice, in 1650 and combined his duties as a Franciscan friar in Venice with studies in cartography. He published hundreds of maps in Atlante Veneto and other atlases during the 1690s. His career as a cartographer flourished with the assistance of aristocratic figures in Italy as well as support from the Church. Coronelli, whose map of China appears above, earned the coveted position of globemaker to the French court under Louis XIV, and his works can be seen today in the British Library and other museums around the world.

But although Coronelli’s outstanding accomplishments are often regarded as the pinnacle of the contribution of priest-cartographers to West European geographical knowledge, the work of his fellow priest-cartographers also had enormous impact.

Around 1680, the French historian and Benedictine monk Casimir Freschot created a series of miniature regional maps in the form of a jigsaw puzzle which, when pieced together, would reveal a spiral map of the world with Venice at its centre. But Freschot’s striking device was not designed just to entertain. He collaborated with the master engraver Anton Francesco Lucini to produce a landmark method of teaching geography to the youth of Venice.

Another key figure was Athanasius Kircher SJ, born near Fulda, Germany in 1602, a prolific scholar who wrote widely about medicine and geology and became professor of philosophy and mathematics at Wurzburg, before fleeing during the Thirty Years’ War to Avignon and later moving to Rome. Kircher had an interest in Egypt – he is sometimes described as the founder of Egyptology – and in the East, drawing on the earlier work of Jesuit missionaries to China such as Martino Martini. Kircher produced an atlas of China, complete with lengthy descriptive passages and social and historical annotations.

Another Jesuit priest and prolific writer, Ferdinand Verbiest, born in west Flanders, now part of Belgium, in 1623, left Lisbon for China in 1658 with Martini and 35 other missionaries. When they reached Macau the following year, only 10 of the travellers remained alive. Verbiest rose to a prominent position under the Emperor K’ang Hsi through his knowledge of astronomy and cartography, as well as his skills as a translator. In 1672, he designed a small steam-propelled trolley for the emperor’s entertainment which has been described as the first automobile, although it is not known whether it was ever actually built.

Verbiest produced highly complex and detailed maps, perhaps reviving the ambitions of his Chinese hosts, who had their own very early cartographical tradition. He died in Beijing in 1688.

West European knowledge and understanding of the geography of Asia was enormously enhanced by these efforts and accomplishments. But the rapidly emerging New World was certainly not neglected.

The Italian Jesuit Eusebio Francisco Kino (1645–1711) founded numerous Catholic missions in Mexico and (what is now) the United States. During his many years in the region, Kino pioneered the study of local geography, producing extensive and accurate maps of the Americas. His skill and observation during his travels led him to suspect that California was not an island, as had previously been assumed, and he produced one of the first maps to show California as a peninsula that could be reached by land from the rest of North America.

Perhaps inevitably, at least one Jesuit priest-cartographer’s attention fell not upon the earth, but on the heavens. Giovanni Battista Riccioli was born in Ferrara, Italy in 1598. In 1651, in collaboration with fellow Jesuit Francesco Maria Grimaldi, he produced the Almagestum Novum, a highly influential collection of 1,500 folio pages of text, tables, illustrations and maps that became required reading for astronomers for many decades. On his maps of the Moon he provided names for features that are still in use today: the Sea of Tranquillity, for example, the site of the Apollo 11 landing in 1969, was named by Riccioli.

The maps of these priest-cartographers showed wide variations but each had their own individual character and “signature”, making them recognisable even today. The maps created by Freschot, for example, may appear to us somewhat rudimentary in comparison with the complexity and ambition of the work of Kircher, but they formed an integral part of geographical education in seventeenth-century Europe.

There is ongoing research in the area, leading to some exciting new discoveries. Alexander Johnson of Antiquariat Daša Pahor, Munich, has investigated the life of another Jesuit priest, Carolo or Carlos Brentano (1694–1752), who created maps of the Amazon region during his work as a missionary in South America. Born in Hungary, Brentano arrived in Quito in 1724 to take up his assignment in the upper Amazon basin.

“Brentano was what I call a frontier cartographer,” says Johnson, “discovering and mapping lands that were either largely or totally unknown to Europeans. Brentano moved around almost frenetically from native village to village over the following eight years, establishing missions and schools. Despite his limited resources, Brentano was able to map this complex region with a relatively high degree of practical accuracy.”

What is perhaps most impressive about the priest-cartographers of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries is the quest that they eagerly undertook to bridge the gap in knowledge between the “old” and “new” worlds.

At a time when explorers, traders and navigators were seeking to exploit the emerging knowledge of the world for commercial and political purposes, they were driven by a very different ambition.

The world is, of course, a smaller place now, with few unexplored regions left. And the big scientific questions today concern areas such as information technology in which the Church and its priests can less easily participate as pioneers. But we can look back on the indisputable importance of the work of the priest-cartographers during a golden era of enlightenment and scientific progress and justly feel a sense of pride.

David Flanagan is a freelancer writer and a collector of antique maps.

17 December 2015, The Tablet

The priests who mapped the world

Missionary cartographers

Edmund for England

Loading ...

Loading ...

Get Instant Access

Subscribe to The Tablet for just £7.99

Subscribe today to take advantage of our introductory offers and enjoy 30 days' access for just £7.99

What do you think?

You can post as a subscriber user...

User Comments (0)