As you read this, Handel’s Messiah is almost certainly being performed somewhere in the world, and the chorus about us being like sheep, with all its tricky runs and flourishes, will be lustily attempted. But are Isaiah’s words really fair to sheep? Disappointingly often, we have certainly gone astray, but is that what sheep do? Do they actually scatter, turning “every one to his own way”? It sounds more like the behaviour of cats. Are not sheep inclined to flock together?

Even if you miss Messiah this Christmas, you are sure to hear Christina Rossetti’s poem “In the Bleak Midwinter”, sung to Gustav Holst’s lovely plaintive melody. Sheep come into this, as well. “If I were a shepherd,” we all fervently sing, “I would bring a lamb.” But would there be any lambs in such a very bleak and snowy midwinter? Would they not be born later, in the early spring, when they could be weaned on to new young grass?

Adrian Brewer, who runs a flock of about 100 sheep in Sussex, says that sheep do, sensibly, stay together for their own protection, though there are always a few that get into trouble. So Isaiah is partly right. As for lambing, in Brewer’s part of the world traditionally the ram goes in on Bonfire Night and the first lambs are born on April Fool’s Day, when spring is in the air. He loves lambing. “It’s the best time of year,” he says. “Nothing is quite so joyful.”

Even in Palestine, though the names are different, the principle remains the same, for winters can be hard there, too, though snow is pretty rare and the earth seldom hard as iron. But Rossetti was probably less concerned with accurate meteorological conditions than with the imagery that surrounds our European vision of Bethlehem, where realism is not a high priority and the stable frequently shelters the blonde mother of an unusually robust infant. And there are always little lambs.

Mary Cox is a sculptor, with a sheep farm high in the Sussex Weald. She has made a statue showing Our Lady as a young woman sitting cross-legged with her tiny baby’s head in her hands, like an orange. She is gazing intently into the child’s face. It is both realistic and profoundly moving. It now lives in Mother Teresa’s house in Calcutta. Mary points out that shepherds at the time of the first Christmas were on the very bottom rung of society “and the message that runs all through the gospels is the value of every individual, and (in Mother Teresa’s words) the importance of the poorest of the poor”.

Since before written history, since the Book of Genesis, since in fact about 10,000 BC, there have been sheep, domesticated first in Mesopotamia and spreading all over the Middle East and throughout the world. They have always nourished us, clothed us, exasperated and enchanted us, as they still do. The care of sheep must be the oldest and most widespread kind of husbandry of all, as the Bible frequently reminds us.

Abel, second son of Adam and Eve, was a shepherd, as were Abraham and Moses. Job had 14,000 sheep and Solomon, at the dedication of the Temple, is said to have sacrificed 120,000 of the poor beasts. King David himself was a shepherd, and knew what he was talking about when, in the Psalm 23, he wrote: “You are with me; your rod and your staff – they comfort me.”

The rod was a strong stick, useful for defence against wolves and snakes: with the staff – now more often a crook – the shepherd could rescue trapped or fallen sheep. The ornate crozier carried by bishops is another tangible ovine metaphor for their perceived role as shepherds of us, their flocks.

Daniel Willard, a practical young shepherd in Norfolk, says that these days they use metal leg crooks, but until recently they always had gentler neck crooks, fashioned from a sheep’s horn. Daniel looks after about 6,000 sheep, on a large parcel of land requisitioned by the army in 1942 and still used for military training. Six villages were evacuated, though their churches remain, churchyards fenced off and, often, windows boarded up. But at St Mary’s, West Tofts, an annual carol service is still held, army bands providing the music. Outside the churchyard fence, Willard’s sheep safely graze, only occasionally interrupted by bursts of heavy artillery, which increase just before an army unit departs for those Middle Eastern territories where the whole thing began.

Not unaware of the ironies, Willard appreciates the Edenic nature of his surroundings, where red, roe and fallow deer live happily undisturbed, grazing on the rare grasses and wild flowers that flourish there. He looks after his sheep all the way from April lambing to eventual slaughter, and has been known to wade, fully clothed, into a lively river to rescue one. What surprises him, though, is that when he tells a stranger what he does for a living, he is met with amazement. “They see sheep all around them,” he says. “But they don’t really believe in shepherds.” Faith dwindles. Our ancestors traditionally learned the whole story of our redemption from so-called mystery plays, in which shepherds played essential roles, providing both broad humour and a special kind of simple narrative reverence.

Willard’s sheep are hefted: each family group occupies a certain area and, even though they are all gathered together for breeding and shearing, they return instinctively to their own hefts. Herdwick sheep in the Lake District are the same. They have a lifelong knowledge of where they belong, which is lucky, for in those high fells, if a stray sheep were to go the wrong way down a steep slope, the farmer could have a 100-mile road trip to fetch it, though fetch it he certainly would. As so often, talking to these shepherds, familiar lines from the Scriptures come to mind: he would leave the 99 and go in search of the missing one.

Mary Cox remembers the night when she and her husband struggled to release a ram caught in a thicket, only for the animal to push further into trouble. Even when it was free, it was covered in burrs and brambles. Inevitably the story of Isaac comes to mind, but the parallel she draws is with Christ the Good Shepherd, whose efforts to save us we often resist. Yet he is also, of course, the sacrificial Lamb of God.

Sheep are prey to many ailments, from brucellosis to pinkeye and daft lamb disease (honestly), and they take a lot of care. But ultimately precious few will die of old age: you could describe them all as sacrificial. These shepherds do know and do treasure their sheep, and it is not too whimsical to suggest that the animals return the compliment: it has been proved that they are able to recognise up to 100 individual people, and they are far from stupid. A sheep in Yorkshire, for example, discovered that by lying on its side and rolling, it could cross an eight-foot cattle grid and happily plunder village gardens: the rest of the flock was quick to follow.

There are many such stories about their ingenuity and their apparent helpfulness to each other. But shepherding can be hard and troubling work. As Brewer says: “You dare not get too fond of them. You see them born safely, you cherish them, you bring them on, they trust you – and then the day comes when you have to whisk them off to the abattoir. It’s never easy.” Perhaps that is why shepherds are traditionally buried clutching a tuft of wool to show their occupation. And, should they need it, to give them an excuse for sometimes having missed Mass.

Sue Gaisford is a former literary editor of The Tablet.

17 December 2015, The Tablet

In fields as they lie

Pastoral scenes

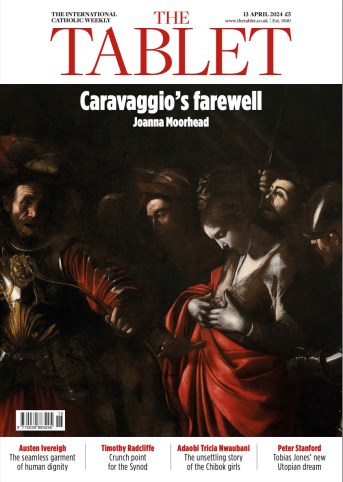

Caravaggio’s farewell

Loading ...

Loading ...

Get Instant Access

Subscribe to The Tablet for just £7.99

Subscribe today to take advantage of our introductory offers and enjoy 30 days' access for just £7.99

What do you think?

You can post as a subscriber user...

User Comments (0)