Last week’s Commons decision to extend RAF air strikes into Syria remains highly controversial. Here, a Conservative MP argues that we must stand by the region’s persecuted, fragile, vanishing religious minorities

Nearly 20 years ago, I spent New Year just north of Damascus.

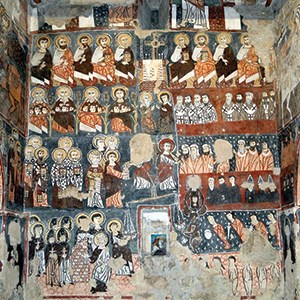

In a 1,000-year-old Chaldean monastery perched on the cliffs, I went to matins as the mist rolled over the mountains from the west and flowed into the Syrian desert. The waves of fog were so thick that the cave in which I slept was invisible from the chapel; then the clouds would clear and we would be warmed by the sun once more. By vespers, the chill of the night had settled in, but the rock, heated throughout the day, kept my cell warm.

The frescoes and altars had been abandoned since the early nineteenth century, until a gentle Italian Jesuit priest evicted the goats and the community was reborn. Speaking beautiful Arabic and with an easy manner, he charmed the neighbouring farmers and semi-settled Bedouin into welcoming the new institution. His initial community consisted of a small company of monks and nuns from around the world and the occasional visitor. Over the years, it grew. Visitors stayed or returned; some took vows. It was the most peaceful place I have ever been.

Nested into the Syrian rock, Deir Mar Musa – the Monastery of St Moses – served as a reminder of the deep roots of Christianity in the region, and the enduring place of monasticism in the Eastern Church. It was also shown that all creeds of the Christian Church could find a place in Syria’s patchwork of religious faiths and communities.

Two years ago, the founding abbot of Deir Mar Musa, Paolo dall’Oglio, was kidnapped and assumed murdered in Raqqa by members of the group calling itself Islamic State (IS). This stripped the community, now mostly in exile, of their inspirational leader. More importantly, as Fr Paolo would himself have said, it marked another step in the tragic collapse of a once vibrant multi-ethnic society, torn apart by the Syrian civil war. With each atrocity, the subtle web of interconnected towns and villages is being torn apart. With each unpicking, not just the region but the world is left the poorer as a history rich and deep is being destroyed in the name of a stark and merciless distortion of a religious creed.

Some have predicted this for years. Interviewing the metropolitan of Damascus in 1998, when I first wrote about Syria for The Tablet, I was warned that the policies of Western governments were leaving the Christian population more vulnerable. For every Christian granted refugee status, he explained, the community shrank and the minority became smaller and more exposed. Slowly the Christian West was stripping the East of congregants, making the accusations that the Christians who remained were “the enemy within” more potent. This, the metropolitan said, would allow communities that pre-dated the Islamic empires to be portrayed as foreigners in their own lands, and make atrocities more likely. Sadly, he has been proved right.

My perspective was different then, as a journalist in Beirut in the late 1990s: it was the Syrian soldiers who held power. Hafez al- Assad, father of the country’s current, beleaguered president, Bashar al-Assad, maintained an uneasy truce between the different factions in the long-running Lebanese civil war.

At the time, it could be argued that by holding back the Hezbollah militias and taking on the Muslim Brotherhood, Assad Sr allowed room for the Christians in Lebanon to survive. In his own country, he maintained a despotic peace which saw tourism flourish and religions coexist.

In the tenth-century bathhouse in Damascus – built by Nur al-Din, the father of Salah al-Din, the Muslim leader who fought Richard the Lionheart – I spent many hours talking to Iraqi Shiites, travelling from Najaf and Karbala to visit the shrines of great Muslim leaders. I shared tea and cigarettes with Sunni Kurds in town to shop before returning to their villages on the Turkish border, and I heard tales of the old country from Armenian Orthodox. It was a meeting place of cultures.

But by the time of my last visit, Syria had changed. Walking through the streets of Aleppo in early 2011, it became clear that one of the oldest religious groups in the region had begun to flee. The preparations for Easter were muted, even as the holy oil was being distributed to the faithful. While I saw the mounting protests having the potential to create a better Syria, I was alone in my hope. My fellow communicants saw their position for what it was – exposed, vulnerable, and protected solely by the uneasy pact their grandparents had struck with the earlier Assad regime. Now the regime was ending, so too was their confidence.

Over the past four years, that thin veneer of peace has been torn away, revealing a violent abyss. Into it have descended not only the Christians but many of the more gentle schools of Islam. Communities and creeds that have existed for centuries, often in remote areas, are now vulnerable to attack as modern weapons make their mountain homes less of a fortress and more of a prison.

The Darwish, whose trance sees them dance to sacred music, are considered apostate and are targets for murder. The Alawis and Druze, who have long been rejected by mainstream Islamic tradition, are now victims of the genocidal certainty of the Islamists. As the war continues, the Syria that I loved is disappearing further and deeper into the past. The languages are vanishing and the mixing of cultures that enriched it is being destroyed.

With remarkable speed, thousands of years of history are being erased. We have watched as Palmyra, an ancient Roman town, was destroyed and the 80-year-old keeper of antiquities brutally murdered. Out of sight, Ma’loula, a village whose inhabitants until only a few years ago still spoke Aramaic, the language of Christ, was fought over by competing Islamist factions.

What remains of the Deir Mar Sarkis (the Monastery of St Sergius, a Roman murdered for refusing to abandon his faith) and the picture of the Blessed Virgin the monks claim was painted by St Luke, remains unclear. The Syria that Father Paolo helped to build is being buried under a wave of hatred and violence.

This is the context in which we must decide how to act. We can wish away the violence but to ignore it – the rapes and murders, the slavery and mass graves – is to ignore the cause of the trauma and the perpetrators. Most importantly, it is to ignore the victims. I am proud that the UK is playing a full part in supporting those most in need by donating more to the United Nations refugee agency (UNHCR) and other agencies than all of the rest of the EU combined. The Department for International Development (DFID) has put more than £1 billion into the camps in Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon and Turkey and has pledged a further £1bn to help with reconstruction. Britain has led international diplomatic efforts and searched for every peaceful solution.

That is why I voted as I did in the House of Commons last week. In my view, it is no longer enough for us to look at the tragic situation in Syria and to wish for peace; we must fight for it. We have seen IS in Raqqa organising to murder Britons in Tunisia, Russians in Egypt and anyone in Paris. It is only good fortune and excellent security work that have prevented an incident in the UK. Today, as it is clear that we too are a target, we must share our part in the burden of diminishing the enemy’s capability to fight and spread their poisonous hatred. It is a tragic reality that pure pacifism can see evil triumph and, today in Syria, that is what we must fight to prevent.

In standing by our allies in France to defeat IS, we are also standing with those who, like Fr Paolo, would seek to bring peace to the region. His enormous courage took him into Raqqa to speak peace with the so-called caliphate; the attack on him shows their interest in such a discussion. Sadly, we can no longer walk by on the other side of the road. This is our battle too, and we have a duty to fight it.

Tom Tugendhat is Conservative MP for Tonbridge, Edenbridge and Malling. A former British Army officer, he served in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Loading ...

Loading ...

What do you think?

You can post as a subscriber user...

User Comments (0)