US bishops gather for their annual plenary meeting in Baltimore next week. How far are they likely to heed Pope Francis’ call to abandon divisive language and conservative positions, and focus instead on dialogue?

Catholics have come to expect harsh language from the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB). When the Supreme Court legalised same-sex marriage across the country, conference president Archbishop Joseph Kurtz called the decision “profoundly immoral and unjust”. The conference has backed a variety of lawsuits challenging the Obama administration’s contraception mandate, with some bishops likening the US president to Adolf Hitler and other tyrants.

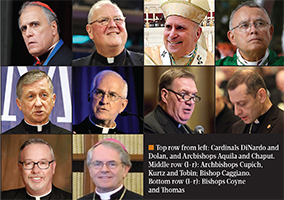

During the recent Synod on the Family, the USCCB vice-president, Cardinal Daniel DiNardo, and the immediate past president, Cardinal Timothy Dolan, signed a letter to Pope Francis questioning the integrity of the synod process and the composition of the drafting committee for the final document.

The conference is divided between those who eagerly support Pope Francis and find his approach compelling and hopeful, those who consider this papacy a patch of bad weather that can’t pass soon enough, and those in the middle who are unsure which narrative is right. The key issue facing them at their annual plenary meeting in Baltimore next week is the degree to which they are going to support the different approach to ministry presented by Pope Francis, or continue on the more trenchant course of recent years, heavily emphasising culture war issues.

This will be the first meeting of the bishops since they gathered in St Matthew’s Cathedral in Washington DC on 23 September for midday prayer with Pope Francis. His message that day was clear: “Harsh and divisive language does not befit the tongue of a pastor, it has no place in his heart; although it may momentarily seem to win the day, only the enduring allure of goodness and love remains truly convincing.” He offered an alternative, encouraging them “to dialogue fearlessly”.

So will the US bishops follow this advice? “Bishops have a definitive choice now,” says John Gehring, Catholic programme director at Faith in Public Life, and author of a new book, The Francis Effect. “They can hit the snooze button and pull the covers over their heads or they can wake up to the new reality that the Pope doesn’t want business as usual. This pontificate offers both a stark challenge and a huge opportunity for a hierarchy that finds itself at a crossroads.”

Archbishop Blase Cupich, chosen by Francis to lead the Archdiocese of Chicago a year ago, told me: “The Pope provided the bishops with a vision of a Church that is synodal, one in which we walk together, so that we can accompany, integrate and reconcile people. Our meeting will no doubt take up that challenge and I anticipate it will help us chart some new and imaginative directions for all of us, both nationally and locally. That is my prayer.”

Which direction the bishops are likely to take will be signalled by three of their agenda items next week: the adoption of new priorities for the conference; changes to their quadrennial document on political responsibility, Forming Consciences for Faithful Citizenship; and their election of new committee chairmen.

At the bishops’ last meeting, in June, the committee charged with drafting the proposal priorities suggested five areas of focus – family and marriage; evangelisation; religious freedom; human life and dignity; and vocations. Nothing about the poor. Nothing about immigration. Nothing about the environment.

Bishop Christopher Coyne of Burlington, Vermont, said the priorities made it look like “we’ve been doing the same thing we’ve always done”. And others rose to second his misgivings. “I really do believe that there needs to be much greater visibility given to the plight of the poor, the economic disparity that so many families feel, rural poverty, joblessness, the struggle of the working poor,” said Bishop George Thomas of Helena, Montana.

Archbishop Joseph Tobin of Indianapolis made the disconnect with Pope Francis explicit, saying, “I would argue that the newness of Francis should condition in a very visible way the priorities as such, so it’s clear that we take him seriously and we’re accepting his pastoral guidance.” After the debate, the bishops voted to accept the proposed list, with amendments to come in November.

The Faithful Citizenship document is not a voter guide per se, but it does highlight some issues as more important than others. Specifically, in 2004, the USCCB introduced the idea that some issues involve “intrinsic evil” and deserve greater attention. Whether an evil is intrinsic – part of its very nature - or not has virtually nothing to do with whether it is of public consequence. Evils, like poverty, can be grave without being intrinsic. The death penalty is not an intrinsic evil, although abortion is. This framing tilted the conference’s political focus heavily towards conservative, Republican issues and away from the social justice concerns on which the Church is usually more aligned with Democrats.

“Catholic social teaching has long been an integral part of the Church’s moral argument for public life. They were never teachings to be ignored,” says Professor Stephen Schneck, director of the Institute for Policy Research & Catholic Studies, at the Catholic University of America, in Washington DC. “Yet, as a pastoral response to the unique moral needs of our age, Pope Francis has brought a profound urgency to these teachings. The US bishops need to convey the same urgency about the Church’s social teachings that Pope Francis has conveyed.”

Schneck believes that changes made to Forming Consciences for Faithful Citizenship will establish the extent to which it will be tweaked to reflect Francis’ priorities.

No one has laboured more over the various iterations of this document than John Carr, who worked for more than 20 years at the USCCB. He says the bishops should listen to the Pope.“They should heed his guidance in their own statement, understanding that the Church and its pastors should be political, but not partisan; principled, but not ideological; civil, but not soft; and engaged, but not used in public life. The test for the bishops and for the rest of us is does our faith shape our politics or is it the other way around.”

Finally, the bishops will have several committee chair elections in which a candidate more clearly identified with the Francis agenda will face a rival more closely identified with the culture warrior model. Some of the races are fraught, such as the one to lead the committee on clergy, Religious and vocations.

Here, one contender, Denver Archbishop Samuel Aquila, attacked the synod proposal of Cardinal Walter Kasper, president emeritus of the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity (see page 10), to find a path for the divorced and remarried to receive Communion, arguing that adoption of the Kasper proposal amounted to a repudiation of Jesus and the saints: “Do the German bishops believe that Sts Thomas More and John Fisher sacrificed their lives in vain?” he asked.

His rival, Archbishop Tobin, was among those advocating the inclusion of more of Francis’ themes in the conference’s priorities.

Another race has a similar dynamic. Philadelphia’s Archbishop Charles Chaput is likely to win the chairmanship of the committee on marriage and family life, even though his interventions at the synod in Rome appeared at odds with the direction the majority of US bishops wanted to take. The other candidate, Bridgeport Bishop Frank Caggiano, has only been a bishop for a few years and is not nearly as well known as Chaput.

Bishops’ conference meetings are always cordial. Disagreements are obvious but there is no shouting or beard-pulling. Most participants end up sharing cocktails at the evening receptions and the small caucus of smokers gather with no ideological intrusions to their gentle banter. But the divisions within the conference are real. By the end of next week, we will have a better indication of just how much the US bishops are willing to let themselves be challenged by Pope Francis.

Michael Sean Winters writes for The Tablet from Washington D.C.

Loading ...

Loading ...

What do you think?

You can post as a subscriber user...

User Comments (1)

For Francis to condemn "harsh and divisive language" is somewhat hypocritical as is his advocacy of synodal principles as long as the synod in questions agrees with him.

Catholics want their Bishops and Pastors to speak the truth plainly even if it sounds harsh to Wuerhl in his penthouse on Millionaire's Row.