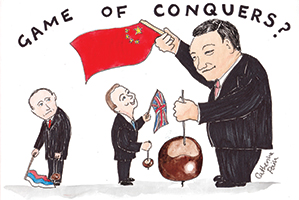

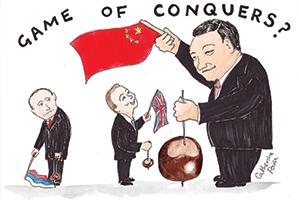

Britain’s criticism of Russia – from its intervention in Syria to its ambitions in Crimea and Ukraine – stands in sharp contrast with our diplomatic overtures to China. Why has the Government left one global power on the sidelines while the other is so warmly embraced?

Vladimir Putin doubtless had more pressing concerns – such as plotting the course of his Syrian war. But what if he had caught even a few fleeting television clips of Xi Jinping’s state visit to Britain last week? Might the Russian president not have been tempted, at the very least, to contrast the British buttering up of Beijing with the hectoring so often reserved for Moscow? And might he then have been moved to ask how different relations might be now, had British governments treated Russia over the past 20 years as they have treated China?

As it happens, I watched some of the Chinese president’s state visit while I was in Russia – near Sochi, on the Black Sea coast, the venue for the latest annual gathering of the Valdai Discussion Club, which meets to talk about all things Russian – and the contrast was sharp. While a beaming Xi was completing his progress around the UK – from a glittering state banquet to “selfies” at Manchester City FC, via fish and chips with the Prime Minister at his local pub – a sombre Putin was wrapping up our gathering with a plea for a new “Vienna congress” of international diplomacy, in which Russia would be included as an equal.

Seen from a narrow British perspective, the juxtaposition exposed a glaring double standard. For UK foreign policy, it seems, there are countries, such as China, where numbers of people and potential pound signs dictate a benevolent agenda; there are others, such as Russia, which must first sign up to our “values”.

A BBC interview given by Chancellor George Osborne during his tour of China last month highlighted the difference with rare clarity. If you replace his every mention of “China” with “Russia”, this is what he would have said:

“My message … is that Britain can’t run away from Russia. Quite the opposite, Britain should run towards Russia … We should be doing more business with Russia. We should be better connected to the Russian economy. Our financial institutions should establish proper links. I think that will help Russia with the important reform and change that it is undergoing, but I also think it is going to help Britain.”

Ah, yes. But would that not be to sell down the Moskva River all those heroic Russian human rights and pro-democracy campaigners we have lionised for so long? Here is Osborne’s response: “Of course, do we disagree about human rights? Yes we do. Does that mean we resile from our British values? Not at all. But isn’t it better to engage and to talk about these things rather than stand on the sidelines and try to conduct some kind of megaphone diplomacy? I just think it is much better we engage.”

Of course. So why is it that UK governments, not just this one, have not engaged Russia, as they have engaged China? And why, if trade is to be the prime driver of British foreign policy, as Sir Simon McDonald, the new permanent under-secretary at the Foreign Office, insists, are we still wedded to the old human rights agenda when we deal with Russia? This was so even before Russia annexed Crimea.

Xi’s state visit exemplified the softly-softly approach to “values” that the UK Government can apply when it wants to. The Prime Minister, David Cameron, said he had raised the subject in their talks, but gave no details. When the BBC’s Laura Kuenssberg asked an admirably provocative question at the joint Cameron-Xi press conference – she described China as “not democratic, not transparent” and as having “a deeply, deeply troubling attitude to human rights” – Xi got away with the following reply: “We combine the universal value of human rights with China’s reality and we have found a path of human rights development suited to China’s national conditions.” Again, try replacing “China” with “Russia” and see how risible it sounds.

A similar double standard applies to trade. The boast was repeatedly made to the Chinese delegation that the UK is “open for business”, and there is perhaps all too much truth in that. Where even the market-orientated United States has evinced qualms, Britain has welcomed Chinese money unconditionally. We relax visa conditions for Chinese shoppers and encourage bulk-buying of London flats; the electronics giant, Huawei, flaunts its presence just off the M4. And now we are to get one, possibly more, Chinese-designed and Chinese-built nuclear power stations. China’s record in Africa may be questionable, and an earlier agreement to redevelop a piece of London’s docklands may be stalling, but the official attitude to Chinese money seems to be “Let it come”.

What of Russia? Whenever Russia has mooted investing in the UK – except via junior oligarchs buying up London property with dubiously acquired cash – the “open” sign is smartly reversed. Nine years ago, Gazprom’s interest in the British gas company Centrica was thwarted on a technicality, officials denying it had anything to do with politics. More recently, the Russian businessman, Mikhail Fridman, had to sell off his North Sea gas interests because of what many interpreted as an overzealous interpretation of EU sanctions. Is nuclear power less politically sensitive than oil and gas?

The British Government’s enthusiasm for China appears to stem from its perceived success as by far the biggest emerging economy. But even if the recent crash of the Shanghai stock market was more of a wobble – and opinions differ – might not Russia have offered an equally stellar example of development, had the UK, and the West in general, not passed up so many chances to engage?

From the G7 London summit’s two fingers to then Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev in 1991, to the hare-brained Western advice that precipitated oligarchism during the Boris Yeltsin years, to the deaf ear turned to Putin’s periodic calls for investment, Britain has helped the West throw Russia back on itself, rather than encourage its opening to the world. Those who took another view – for example, Germany’s former Chancellor, Gerhard Schröder, with the gas pipeline, Nord Stream – were branded collaborating profiteers.

Not that everyone agrees the UK should soft-pedal human rights when dealing with Russia, just as not everyone accepts the Government’s seemingly unconditional embrace of China. Dissenters expressed their views forcefully before and during Xi’s visit. They regard British China policy as scandalously mercenary and condemn Cameron and Osborne for undue leniency towards Beijing on “values”. If they also support the Government’s continued hard line against Russia, they can at least claim consistency. Their views are entirely defensible.

Whether you are an idealist or a realist in foreign policy, however – and, personally, I tend to realism – you have to ask why the UK treats Russia and China so differently. From building artificial islands in the South China Sea and oppressing Tibet and Xinjiang, through the violence against pro-democracy protesters in Hong Kong, to the murder and detention of British businessmen, and its hostile attitude to Christianity which is the fastest-growing religion in China, plenty of bad behaviour can be laid at China’s door. The only logic in the British position would appear to be that of the playground: the bigger you are, as a population and an economic prospect, the badder we will allow you to be.

But could the converse also be true? If the Government had shown as much indulgence towards Russia over the years as it is now showing towards China, might our relations with Russia now be calmer, more respectful and more mutually advantageous? And might Russia have behaved better, both at home and abroad, if it had been part of a wider international conversation, and understood that it had relationships to lose?

Before President Xi’s state visit, the British Government’s hope was for a “golden decade” in relations with China. What a pity, what a reflection of lost opportunities, that the same cannot be said of Russia.

Mary Dejevsky is a specialist writer in foreign affairs.

Loading ...

Loading ...

What do you think?

You can post as a subscriber user...

User Comments (1)

Very interesting article.

It is true UK is not consistent or logical when dealing with China AND Russia.

I sense a theme. Can one also say the same about the UK's views in regards to Saudi Arabia and Iran.

It appears the UK does not view Christianity as important, but it views trade as the one thing that TRUMPS all. America and the UK show the world what is of importance. It is trade, not Christian values.

I wonder if the terrorist knows this.

This may bite us one day.