This week’s appointment of a new head of the Congregation for Divine Worship will reopen the debate about how the Church makes decisions on the liturgy. Some want to start by revoking the Vatican document that led to the new Missal

Pope Francis has signalled that we are in a new moment. Surprises are the order of the day; some have to do with style and tone, others with substance and priorities. Because of my keen interest in the liturgical life of the Church, I find myself thinking how different things might have been had Francis been elected just a few years earlier.

For one thing, I am quite certain that the Missal would not be the one we are still trying to get used to. More likely, it would resemble the one that was painstakingly produced over a period of 17 years by the International Committee for English in the Liturgy (Icel), only to be rather unceremoniously consigned to oblivion by Vatican officials who had got it into their heads that liturgy had become too casual and colloquial.

One can’t rewrite history, of course, but one can speculate. And as I do, I acknowledge that the Missal is not world poverty or world peace. And while the liturgy is, as the Second Vatican Council teaches us, “the source and summit of the Christian life”, within the Church’s life the quality of the English translation in the Missal is not on a par with evangelisation, an enhanced role for women, collegiality, or even curial reform. But that is not to say it’s not important.

Three years after the new Missal’s introduction, it is hard not to note the serious dissatisfaction many continue to experience with it. It is not all bad, of course – some of it has genuine merit. But the problems are legion. And that emboldens me to suggest, not that the new Missal be revised (it is probably too soon for that and, besides, many priests seem to be doing that on their own) but rather that the 2001 document from the Congregation for Divine Worship, Liturgiam Authenticam, which governs liturgical translations, be revoked. This is something that should be done as soon as possible, certainly before any further translations are made.

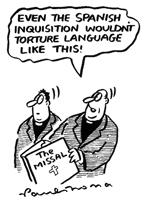

I make the suggestion because our public prayers should not be second-rate compositions that would earn poor marks in any secondary-school English (or theology) class. Think, for instance, of all the tortured grammar and syntax in the Missal – not to mention the jerky, whiplash phrasing, which leave priests scratching their heads (or sometimes stifling a smile) and the people in the pews simply tuning out. Think, too, of the tone of the prayers, with their exaltation of merit over mercy, their emphasis on human weakness at the expense of human dignity.

So many times during Mass, I have been tempted to stop and ask, “Does anyone know what that means?” But I don’t have to ask. One disgruntled parishioner told me that, as far as she was concerned, “some of those prayers might as well be in Latin”.

Complaints from the priests and from the pews are not simply hearsay. A survey conducted by the highly regarded Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate at Georgetown University, in Washington DC, makes it clear that in the US the level of dissatisfaction, particularly among priests, is resounding and decisive. The Tablet’s own online survey of opinion, published in February 2013, a year after the new Missal was introduced, was less scientific, but suggested that in the UK and Ireland, laity and, overwhelmingly, priests were even more critical of the new translation.

All of this was predictable because comprehension and clarity of expression were far less important for the translators than English texts formally equivalent to the Latin originals. Such was the holy mission of Liturgiam Authenticam, which, in changing the principles guiding liturgical translations, demanded strict adherence to the Latin. In doing so, it set the stage for tortured translations – and also robbed the bishops’ conferences of the decisive role in liturgical matters guaranteed them by the Second Vatican Council. As long as this document is in force, the danger is that we will continue to get translations that sound more like Latin than English.

There is, however, more to consider than style and syntax. Much more. There is Pope Francis and the new moment he has brought to the Church and the world – the fresh air, the invitation to dialogue, the resetting of priorities, the quest for simplicity, the desire to remove barriers and to communicate with people. There are also his writings, most prominent among them his apostolic exhortation, Evangelii Gaudium. Reflecting on that groundbreaking document has made people sit up and think about many things and, while the Pope does not focus on the Mass or the Missal, he does talk about language, communication, modes of expression and cultural adaptation – all of which have significant implications for the way we pray.

With regard to language, Pope Francis warns priests against the use of “words that are suitable in theology or catechesis, but whose meaning is incomprehensible to the majority of Christians”. Instead, he points to the importance of simplicity, clarity, directness and adapting to “the language of the people in order to reach them with God’s word … and to share in their lives” (EG 158). In the light of this, how can we justify using words such as “consubstantial”, “conciliation”, “oblation”, “regeneration”? All of these might suit theology books, but not the ears of the average hearer.

In Evangelii Gaudium, Pope Francis also goes after the sacred cow of ancient Latin texts. He writes: “We cannot demand that peoples of every continent, in expressing their Christian faith, imitate modes of expression which European nations developed at a particular moment of their history, because the faith cannot be constricted to the limits of understanding and expression of any one culture” (EG 115).

Amen to that. The principles of Liturgiam Authenticam run precisely counter to Pope Francis’ vision. Far from drawing on the gifts of culture, it stifles them in favour of a monoculture. Contrast the words of Pope Francis with the directive Liturgiam Authenticam gives to the Church in the developing world: “In the translations intended for peoples recently brought to the Christian faith, fidelity and exactness with respect to the original texts may themselves sometimes require that words already in current usage be employed in new ways, that new words or expressions be coined, that terms in the original text be transliterated” (LA 21). Such slavish attention to the Latin is bound to result in translations that are museum pieces – about as fresh as a fossil preserved in amber. This is precisely the kind of cultural imperialism that Pope Francis has called into question.

Public comments made by two American bishops, Wilton Gregory (of Atlanta) and Robert Lynch (of St Petersburg, Florida), at a national meeting celebrating the fiftieth anniversary of the Second Vatican Council’s decree on liturgy give some hope. So too does the continuing outspoken opposition of such figures as Maurice Taylor, former Bishop of Galloway (and former chairman of Icel). Could this be the start of a groundswell to change the rules for translations? And, if so, is it possible that, like their confrères in places such as Germany and Austria, who have firmly held the line against translations made according to flawed norms, the English-speaking bishops will now find themselves emboldened to speak up and speak out?

That would accord with the direction Pope Francis is taking. More than once he has spoken of the need to reinstate the validity of the bishops’ conferences and their authority to decide matters that pertain to the local Church. He writes: “It is not advisable for the Pope to take the place of local bishops in the discernment of every issue which arises in their territory. In this sense, I am conscious of the need to promote a sound ‘decentralisation’” (EG 16). He also urges the whole Church, both clergy and lay, to take a new approach to these questions: “I encourage everyone to apply the guidelines found in this document generously and courageously, without inhibitions or fear” (EG 33).

Encouraging words! And Pope Francis’ recent shake-up of the leadership of the Congregation for Sacraments and Divine Worship – with the appointment of Cardinal Robert Sarah of Guinea as its new prefect in place of the Spanish Cardinal Antonio Cañizares Llovera – might set the stage for a thorough review of how liturgical decisions are made and who makes them.

In the wake of the recent changes at the Vatican, the bishops should call for the repeal of the unfortunate Liturgiam Authenticam and the elimination of its handmaid, Vox Clara. That would be a game-changer. Until recently, the very thought of such a thing would have been dismissed as naive or radical, but it is a new moment. And a new moment calls for a bold new initiative.

What are we waiting for?

Michael G. Ryan is rector of St James Cathedral, Seattle.

Loading ...

Loading ...

What do you think?

You can post as a subscriber user...

User Comments (0)