‘Most were driven by a sense of comradeship and community, values often ignored nowadays’

“There is no period so remote as the recent past,” says the cocky supply teacher, Irwin, in The History Boys. Though he is talking of the Holocaust, his quip is particularly applicable to the current debate and controversy about the commemoration of the First World War.

The experience of that conflict now lies just beyond memory. Today, there are no veterans among the ranks of great grandfathers, grandmothers and remote cousins to conjure direct recall of the war and its aftermath. Harry Patch, the last surviving Tommy who saw battle on the Western Front, died in July 2009 at the age of 111.

Myth jostles with history as we try to establish what happened on the ground and why it matters to us now. Almost every aspect of the war, its preliminaries and aftermath, is a matter of dispute. At the time of the armistice on 11 November 1918, Britain, its allies and dependencies, were still involved in more than two dozen conflicts across the world. Irishmen stopped fighting only after a bloody civil war and the recognition of the Irish Free State in 1923. The historian Eric Hobsbawm saw 1914 as the beginning of a continuum of war – the “age of extremes” – which ended with the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989.

The First World War was the first direct experience of total, industrialised warfare shared by the population of Britain as a whole. Until recently, there was hardly a family in the land that was not touched by it, with a close relative killed in action or damaged for life. Around 1,100,000 citizens of Britain and the Empire died, among them 44,000 colonial labourers, many from China and India. Altogether some 16 million fell in combat and 21 million were wounded. As many young men would die from the Spanish influenza epidemic from 1918 to 1920 as were killed fighting in Western Europe.

In popular myth, the war has become an exercise in futility, whose vivid symbols are the austere ranks of headstones in the official War Graves Commission cemeteries. The sense of despair has been shaped by the generation of poets writing in the war and about the war – which, in turn, informed the biting satire of Joan Littlewood’s Oh What A Lovely War and Blackadder Goes Forth. The despair is summed up by Wilfred Owen’s declaration, “My subject is War, and the pity of War. The Poetry is in the pity.”

Recently there has been a growing riposte to what is called “the poets’ vision of the war” from a group of conservative historians and journalists who argue that, far from being an unnecessary waste, the war had to be fought against the burgeoning evil of German militarism. The British Army is planning to commemorate its role in winning the struggle on the Western Front with the series of bloody offensives of the “hundred days” in the late summer of 1918.

This Christmas The Economist dedicated its first leader to the commemoration of the First World War, very much in the triumphalist spirit. It declared that “the driving force behind the catastrophe that befell the world a century ago was Germany, which was looking for an excuse for a war that would allow it to dominate Europe”. As the examiner would say – discuss. On the other hand, the historian Niall Ferguson has argued that Britain was as much to blame as Germany, an economic rival to the British Empire. Ferguson believes that Britain has much to answer for in that it did not stop the slide to war when it could.

A great deal of such argument seems beside the point. It does, however, highlight the broad depiction of the First World War as a bad war, whereas the Second World War was the good one – or at least fought for good and high-minded reasons. Both propositions are almost ludicrous distortions. The Second World War was far more destructive of human life and over a far greater area of the planet, and was fought for equally mixed motives. Britain did not go to war to defend the Jews of Europe, and victory was delivered by alliance with Stalin, one of the more egregious tyrants of history.

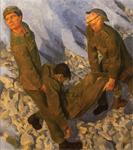

The problem with the First World War is that the motivations and causes for which most fought, and continued to fight, are so utterly remote from the values of most of us today. Most were driven by a sense of comradeship and community, a belief in public duty – civic values often derided, sneered at, or ignored nowadays. Exceptionally, of all the major combatant powers, the British armies did not mutiny to any serious degree.

This difference of values – between then and now – contrasts with the American Civil War, with over 600,000 combat deaths a hugely destructive conflict, whose one-hundred and fiftieth anniversary is now being commemorated, most conspicuously by a series of illuminating articles on The New York Times blog. Issues such as secession, individual liberty, racial equality and national unity in a diverse federation of states, are still very much alive in the United States today.

Much of the commemoration of the centenary will concentrate on the stories of individuals, families and communities – understandably so. But this should not displace the asking of the wider questions and the attempt to set the First World War in context. As much as commemorating the dead, we should ask about what happened to the wounded in mind and spirit; too little is mentioned about their impact on our world. Ivor Gurney, musician and poet, for instance, died in a psychiatric institution in 1937, never quite believing the war had ended.

On the other hand, too, some space should be given to the spirit of those few dozen war memorials, like the granite cross at Rookhope, high on the moors in County Durham, where the names of those who survived and returned are recorded beside those of the dead. Nor should we look at the experience through a uniquely British lens. War poets as great or greater than the British wrote in Russian, German, French and Italian.

The First World War is sure to remain a great mystery in many respects. Quite why it began in July and August 1914 is difficult to fathom – a lot of crucial diplomatic material has been destroyed. As important, argues Margaret MacMillan in her brilliant new book, The War That Ended Peace: the road to 1914, is the question of why the mobilization was not stopped. After all, conflict had been averted in several crises over the preceding 30 years.

The First World War changed Britain, Europe and much of the world forever. Empires fell, and states based on new identities of ethnicity and nationhood arose. The Ottoman Empire was carved up by Russia, France and Britain to make the new Middle East, and has been in conflict ever since. New creeds of totalitarian populism were born. The war brought new language and attitude – it shaped our modern memory, to borrow the title of Paul Fussell’s great work on the war poets, The Great War and Modern Memory. It is up to each generation to reach its own understanding of the legacy. This is the thesis of another of the outstanding books on the anniversary, Professor David Reynolds’ The Long Shadow: the Great War and the twentieth century.

In our own time we are commemorating the centenary in the wake of two long conflicts, in Iraq and Afghanistan, where British servicemen and women were ordered to action on the almost optional choice and whim of their political masters. For most of us, war is an exotic and difficult experience, largely remote from our lives. Then, as now, though today on a very much smaller scale, there is the sense of disillusion – a questioning of what such long years of combat and concentrated killing has benefited us. Here the reflections of Pope Francis on the bewildering ferocity and futility of current conflicts – from Syria and the Gulf to the Saharan Sahel in Africa – seem especially apposite. His particular insight on the futility of the cult of violence, whether waged by states, sects or autonomous paramilitary powers, is a main element of his message to the world, according to James Carroll in his milestone essay on Pope Francis in last month’s New Yorker.

Again there is a parallel with the sense of disillusion as hostilities ended in Europe in 1918. “After the war to end all wars, I suppose we’ll have the peace to end all peace,” reflected the young Archibald Wavell, then serving on Allenby’s staff in Egypt and Palestine. But he and his fellow junior officers did not expect too much. Faith, even among the most devout, had been strained to the limit. Many turned to the occult, séances, table turning and Ouija boards, in the desperate attempt to reach out to dead loved ones.

Most in Britain, France, America and Italy were aware of the terrible cost, and in families like mine it would mark them for generations. When it came to the dedication of Britain’s national memorial, Lutyens’ Cenotaph, the ceremony was that of an Establishment and nation in deep in mourning and shock. This is brought out in the haunting description in David Crane’s Empires of the Dead, another outstanding new book on the war, this time focusing on the establishment of the War Graves Commission. The same communal grief and bewilderment accompanied the equally harrowing burial rite of the Unknown Soldier in Westminster Abbey. While Catholics pray for the departed souls and request intercession for them, Anglicans and Protestants commemorate and mourn their dead, and often leave it that.

In another sense, the context of the outbreak of the First World War is very similar to our current experience. The world of 1914 seemed blessed by huge benefits of new global technology, in communication, medicine, transport and home comforts. Yet, as Margaret MacMillan points out, the creaking political order did not feel fully in control of its subjects or their destinies. So matters slid to total war. A similar unease about the competence of the political order and the effectiveness of governments to master events billows through the global media of today.

Understanding this is the legacy of the First World War. And with it comes the obligation to honour the dead, and the injured in body and spirit, who decisively shaped our modern memory.

* Robert Fox is defence editor and foreign commentator of the London Evening Standard and a commissioner for the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

02 January 2014, The Tablet

The world turns – centenary of the start of the First World War

Looking forward to 2014

Edmund for England

Loading ...

Loading ...

Get Instant Access

Subscribe to The Tablet for just £7.99

Subscribe today to take advantage of our introductory offers and enjoy 30 days' access for just £7.99

What do you think?

You can post as a subscriber user...

User Comments (0)