Atul Gawande, the doctor and Harvard professor who gave this year’s BBC Reith Lectures, has spoken powerfully of what he calls “the problem of hubris” – the medical profession’s insistence that doctors must always have a treatment to offer their patients even when they are entering their final days. The professional focus on recovery sees death as a failure. Gawande admits that he himself has offered the terminally ill experimental treatments rather than accept what felt like defeat.

The report this week from the parliamentary and health service ombudsman into end-of-life care in the NHS makes for disturbing reading. It found that many patients endure undignified and painful deaths. The refusal to accept that someone is dying can be the root of the problem. Rather than switch to palliative care, doctors preferred to try treatments that often proved useless, merely prolonging a patient’s distress. Sometimes they were not even told they were dying.

The recognition of this problem by Dr Gawande and others suggests that medical culture could change, with doctors seeing death as inevitable and natural, requiring pain control and allowing time for important conversations. Hospices have shown how effective this approach can be, bringing peace of mind instead of suffering and neglect. Further changes are required: it is not acceptable for the NHS to offer a bureaucratic response to dying. The ombudsman highlighted that only 19 per cent of NHS trusts offer palliative care, and then only during office hours.

An even more profound shift is needed in attitudes to death in society in general. With progress in medical science leading to greater longevity, and hospital rather than home care reducing people’s familiarity with dying, death has become unfamiliar territory. As another study published this week by the Dying Matters Coalition revealed, few people ever speak about death, or articulate their wishes for their funeral. In this secular age, it is not only doctors who lack the vocabulary to deal with death. The experience of Rosie Harper, an Anglican vicar who writes in The Tablet this week, suggests that local church communities that have retained this language can help people gain confidence to talk about last things.

Contemporary life places great store on autonomy. One of the greatest fears of many people is lack of control, a fear conveyed in the demand for “dignity”, a word often linked with euphemisms for enabling the terminally ill to end their lives. In the last 10 years, five bills have been tabled seeking to change the law on assisted dying and, while all were defeated, a YouGov poll commissioned by Dignity in Dying at the time of the last attempt in 2014 found three-quarters of respondents said they would support a bill to legalise assisted suicide. The revelations of this week’s ombudsman’s report give some indication why support has been so strong. The NHS has made substantial improvements in its maternity care. If it is truly to be a cradle-to-grave service, it must rethink fundamentally the way it deals with the dying.

21 May 2015, The Tablet

Right to a good death for all

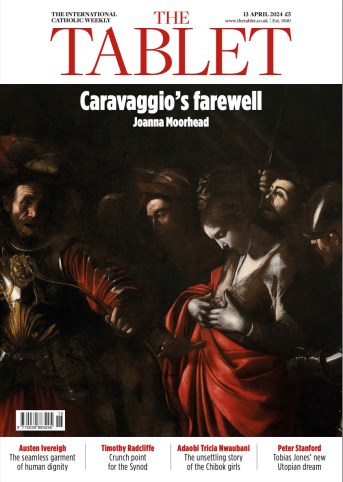

Caravaggio’s farewell

Loading ...

Loading ...

Get Instant Access

Subscribe to The Tablet for just £7.99

Subscribe today to take advantage of our introductory offers and enjoy 30 days' access for just £7.99

What do you think?

You can post as a subscriber user...

User Comments (0)