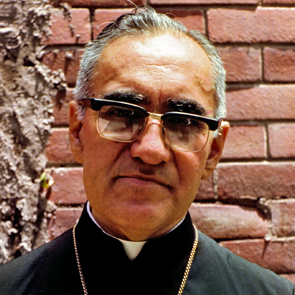

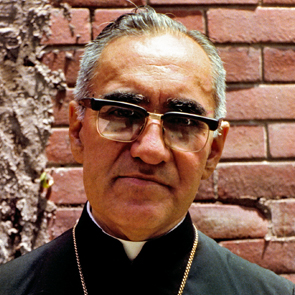

Pope Francis approved a decree stating that Archbishop Oscar Romero was killed in "hatred of the faith", paving the way for his beatification. The Salvadoran prelate was gunned down by a right-wing death squad linked to the Government of the day. Romero had spoken out against the regime and in favour of the poor. But does that make him a martyr? The question is whether he died as a political dissident or for championing gospel values.

This Tablet article, from 1993, points out that Pope John Paul II warned him to be wary of “what could result from a score-settling on the part of the popular left, which could also be bad for the Church”.

When we initially reported the murder Cardinal Basil Hume, noted his “supreme sacrifice”, which he said was the “climax of his peaceful struggle for [the] poor and oppressed”.

Murder in the cathedral

Peter Hebblethwaite

Oscar Romero was chosen as Archbishop of San Salvador because he was a conservative. Within weeks he had become radicalised. The biographer of Paul VI reviews the pastoral letters and sermons of a man who is already revered locally as a saint, but whose witness made him enemies both in Church and State.

Throughout history there has always been something about the death of an archbishop that has caught the Christian imagination. It is not that the life of a major churchman is worth more than any of the baptised, but a violent archiepiscopal end dramatises the conflict with secular rulers and declares that no one, king or potentate, is above the law — human law or the law of God.

Like St Stanislaw, murdered in Krakow by order of King Bodeslaw II in 1079 and St Thomas Becket, hacked to pieces in his cathedral on 29 December 1170, Oscar Romero by his death on 24 March 1980 entered the martyrology and became an international figure.

If it be objected that the process of discernment which will one day declare Oscar Romero Blessed has only just begun and that his murderers are still around, the reply is that the people of San Salvador did not wait for papal approval any more than did the people of ICrak6w and Canterbury. Romero's cult is already deeply rooted. Pope John Paul has prayed at his shrine (though we do not know what he prayed for).

According to Gustavo Gutierrez, Latin American church history divides into before and after Romero.

The formal process of beatification is often held up — says the Congregation for the Causes of Saints — because we do not have sufficient evidence about the candidate or because there are few witnesses to his life and death. This is certainly not true of Oscar Romero. After James Brockman's admirable biography, and the reflections of Jon Sobrino, the publication of Romero's own pastoral letters and sermons, A Shepherd's Diary, tells us as much as is likely to be knowable about Romero's spiritual outlook.

The modern historian curses the telephone, because it leaves no traces and led to a decline in letter-writing. In compensation, however, there is fax, which is post Romero, and the tape-recorder. Romero communed almost daily with his taperecorder and this diary is the result. It has little in common with Pope John XXIII's Journal of a Soul. It was not intended as a record of graces received. Romero's inner life of prayer appears only indirectly. But that is saying a lot, since his prayer was a constant effort of discernment, of seeking the will of God in a situation fraught with danger, misunderstanding and complexity.

Romero started his diary on 31 March 1978, just over a year after becoming Archbishop of San Salvador. The two most important events of his life had already happened. An auxiliary bishop since 1970 and in charge of the rural diocese of Santiago da Maria from 1974, he was named Archbishop of San Salvador because of his reputation for conservatism. "El Salvador's oligarchy of wealthy landowners", Brockman explains, "wanted an archbishop who would change Archbishop Luis Chavez's policies and stop the preaching about social justice and the rights of the poor."

The irony is that the oligarchy's expectations were absolutely right. Romero, close to Opus Dei, was their man. But then, only three weeks after his episcopal ordination, the Jesuit Fr Rutilio Grande was gunned down in his jeep, with a boy and an old man. This event triggered Romero's "conversion". He closed all Catholic schools for three days of mourning and ordered that, on the Sunday following the Requiem, there would be only one Mass in the square before the cathedral. That set the scenario for an episcopal ministry shocking both to the Salvadorean establishment, to the papal nuncio and to the majority of bishops whose metropolitan he was.

This is the context in which Romero started to keep a diary. He does not say why he kept it. Fr Brockman's explanation — that he had one eye on history — is not wholly convincing. Perhaps he just wanted to keep track of his endless meetings and conversations so that he could refer back and show his consistency of purpose. The diary is a record of his daily meetings; but it is also evidence for the defence.

Being a bishop is no joy ride. For Romero it was a crucifixion, as the different loyalties he was possessed by tore him apart. He put communion with the Holy Father, the Bishop of Rome, first. In Rome in May 1979 he prayed at the tombs of modern popes and reflected: "I asked for great faithfulness to my Christian faith and the courage, should it be necessary, to die as those martyrs died, or to live a consecrated life as those modern successors to Peter did. More than any of the other tombs, I am impressed by the simplicity of Pope Paul VI's tomb."

Romero had a private audience with Paul VI six weeks before the Pope's death on 21 June 1978. He could not remember the exact words but recalls the gist of what was said to him: "I understand your difficult work. It is a work that can be misunderstood; it requires a great deal of patience and strength." The dying Pope exhorted him to courage and hope. From Paul VI that has an autobiographical ring.

It was only when he left El Salvador that Romero really became aware of the denunciations that were discrediting him in Roman eyes. At Puebla in 1979, the Salesian Bishop Pedro Aparicio of San Vincente tried to undermine his own archbishop by blaming him and the Jesuits for the violence in El Salvador. At a meeting with Fr Cesar Jerez, then Jesuit provincial of Central America, it was suggested that Romero was not the real target of those responsible for the "crypto-Marxist" calumny, but rather Don Pedro Arrupe, the Jesuit General.

Romero naïvely believed that having the Jesuits on his side would help him in Rome. On his next visit in May 1979 this old boy of the Gregorian was grateful to them for providing him with a room in which he could have a siesta. He also fussed about getting a crozier like that used by Paul VI and John Paul II.

But he found meeting the new Pope difficult. He was made to hang about. He should have been more alert to the signs. Someone warned him that the trouble came from the writings of Jon Sobrino SJ. Cardinal Eduardo Pironio, then prefect of the Congregation for Religious, opened his heart "telling me what he has to suffer, how deeply he feels about the problems of Latin America, and that, even though they will never be completely understood by the highest levels of the Church, nevertheless we must keep working".

"The worst thing you can do", Pironio advised, "is to become discouraged." But it was difficult to heed this advice, given that enemies in his own camp like Bishop, Aparicio had got in first with their disinformation. His meeting with Pope John Paul II took place under a cloud. "He recommended great balance and prudence", Romero notes, "especially when denouncing specific situations. He thinks it better to stay with principles, because with specific accusations there is a risk of making errors or mistakes." Romero tried to explain that some very specific murders in El Salvador were not adequately covered by stating general principles.

But he got nowhere and learned that he was in effect to be deprived of effective authority : the "apostolic visitation" of the Argentinian Bishop (now Cardinal) Antonio Quarracino recommended the appointment of an "apostolic administrator" to sit alongside him and do his work. Only death spanlid him this humiliating "solution".

On his return home there were deaththreats adorned with swastikas from the right-wing Union Guerrera Blanca "order ing me to change the way I preach, telling me I must condemn Communism, that I must praise the members of the security forces that are killed, etc., and that if I do not do what they say, they will kill me". Romero charitably understood these to be psychological threats.

But they were real enough for Fr Rafael Palacios, a martyr who had replaced another martyr, Fr Octavio Ortiz, as parish priest. "Be a patriot, kill a priest" was a slogan of the time. Why should priests be killed? Romero answered by "analysing the situation of injustice and sin that a priest must denounce. And that means being unappreciated, being a persona non grata to society which, like Jerusalem, kills the prophets". It was a claim he never made for himself. The denouement was at hand without any clear sense of foreboding.

On 22 January 1980, the National Guard machine-gunned a peaceful demonstration, and the survivors took refuge in the cathedral and — some 40,000 thousand of them — the Jesuit university. The government said the troops had been provoked. Foreign reporters denied this. Romero fair-mindedly ordered an investigation.

There was one more interlude before his own death. He went to Louvain to receive an honorary degree and used the occasion to go to Rome for the last time. Cardinal Pironio, franker than ever, said that "while those who kill the body are terrible, those who wound the spirit and destroy a person with lies and defamation are even worse. And he thinks that this is exactly the martyrdom I face even within the Church itself and that I must be strong".

From Pironio he went to Pope John Paul II, who said "we should be concerned not only with defending social justice and the love of the poor, but also with what could result from a score-settling on the part of the popular left, which could also be bad for the Church".

Romero replied: "Holy Father, this is precisely the balance that I try to keep because, on the one hand, I defend social justice, human rights, love of the poor. On the other hand, I am always greatly concerned for the Church, and that by defending these human rights, we do not become victims of ideologies that destroy feelings and human values."

This audience was on 30 January 1980. Romero was killed on 24 March as he said Mass in the chapel of the Divine Providence Hospital where he lived.

He was probably the first martyr who consulted a psychiatrist friend about his fears. He had memorably said to a Mex ican journalist days before his death "Martyrdom is a grace of God that I do no believe I deserve. But if God accepts th( sacrifice of my life, let my blood be a see( of freedom and the sign that hope will soo become a reality. Let my death, if it be accepted by God, be for the liberation ( my people." Thirteen years on, as peace ( a sort returns to El Salvador, it seems th he has been vindicated.

Loading ...

Loading ...

What do you think?

You can post as a subscriber user ...

User comments (0)