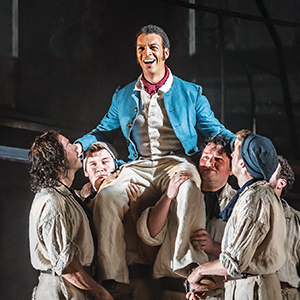

Billy Budd

Opera North, touring

Every real opera composer has a unique thread running through his work: for Handel, compassion; for Mozart, reconciliation; for Wagner, redemption. Benjamin Britten’s fixation was innocence, its fragility – and its destruction.

Time after time he returned to the theme: the dead apprentices of Peter Grimes, Lucretia’s suicide, the ruined children of The Turn of the Screw and, in Billy Budd, based on Herman Melville’s 1891 novella, the 1797 execution of the darling of HMS Indomitable for involuntarily killing the ship’s master-at-arms John Claggart.

In its starkest terms, Billy Budd is a none-too-subtly drawn conflict of good and evil. Claggart is a satanic irruption, a serpent, pure malice, while Billy is radiantly good, transformative. It is a metaphor both of the fall of man and of his redemption: as Billy is hanged from the yardarm, his body is silhouetted against the crosstrees as dawn bursts over the sea with impossible effulgence.

Claggart instantly takes against Billy, who has been pressed into service from a passing merchantman, though he eagerly welcomes the career move. The source of Claggart’s animosity is shadowy – and in any case Melville is at his most enigmatic in the convoluted prose of Budd – but we understand that it is based on blind hatred of beauty and goodness.